Sustainability

Introduction

In the current chapter, we will rely as much as possible on the 2022 Sustainability chapter. If you haven’t yet, you should read it right now. Yes, recycling/reusing is a major part of sustainability.

Since the 2022 Almanac, the field of digital sustainability has advanced considerably. That said, it is very much in its infancy, as this is a complex problem. We cannot know, with absolute certainty, what the full effects of our digital lives are on our physical planet. What we can be confident in is that the full impacts are bigger than generally accounted for. Water, land, rare minerals, and electricity are all consumed by our “clean” digital interfaces, and toxic waste is often produced.

In addition, it has been recognized by many working in sustainability that the impact of other primary fields such as web performance, accessibility, security, privacy, etc. can lead to emissions as a secondary consequence of poor planning and decision-making.

Since the last Almanac, we have seen the creation of open standards, open source software, and open data on the impacts of our digital lives. Although still in development, we have the beginning of an evidence-based approach to emission reductions. There are courses, certifications, books, videos, podcasts, and conferences on the subject. Yet, this is still an issue that takes backstage with other efforts to reduce emissions.

We need to get better at reducing the impacts of our data centers and start seeing digital devices as part of a circular economy. But more importantly, we need to begin reducing our demand for more and bigger digital experiences.

Where possible, we will be leveraging the Draft W3C Sustainable Web Community Group Web Sustainability Guidelines (WSG). We will be building on the experience of the 2022 Almanac to highlight data to give us a snapshot of where we are today.

But first, here’s a quick recap of what happened in the sustainability field since 2022.

What’s new in web sustainability?

Since 2022, we have seen a steep increase in awareness of web sustainability. Along the way, a lot has happened.

The Software Carbon Intensity (SCI) Specification has become an ISO standard. Based on the rate of carbon emissions, this specification is a way to track the environmental efficiency of a digital service. This could be a good starting point. However, it could be important to go further through additional ecological factors (depletion of abiotic resources, water usage, etc) and consider all steps of the lifecycle of a project to reach for frugality and moderation.

This quest for efficiency saw some other achievements such as carbon-aware code and major cloud providers aiming for a reduction of their environmental impacts, mostly based on carbon emissions. Sustainability also met some drawbacks because of the rise of artificial intelligence, which in itself gets massive media coverage but not necessarily for its environmental impacts. This emergence hindered the efforts of some major cloud providers to reach for the reduction of environmental impacts. This helps illustrate that efficiency is not enough and frugality should be our top priority. It also highlights that widely adopting new technologies without considering their environmental (and social) impacts should be avoided.

This is where we should mention new repositories for best practices:

- The W3C (World Wide Web Consortium) Sustainable Web Community Group published the Web Sustainability Guidelines (WSG) 1.0. These offer a higher perspective on web sustainability and should help teams adopt sustainability on a larger scale (more on this later in this chapter).

- France institutions also released the General policy framework for the ecodesign of digital services. The purpose here is to offer a framework for sustainable digital services and to aim for a wider adoption of these best practices.

- An ISO standard for Digital Services Ecodesign is also on the way.

More and more books are also being published, such as Building Green Software by Anne Currie, Sarah Hsu and Sara Bergman.

In addition to this, tools for estimating the environmental impacts of the web are still evolving and new ones keep appearing. Some existing tools (such as Screaming Frog SEO and Webpagetest) are adding features to estimate environmental impacts. As such, the Sustainable Web Design Model is often used. However, accurately estimating impacts is still an important topic and no consensus has been reached yet. As is often the case with environmental considerations, the topic remains complex.

To give more context to all these breakthroughs, more general studies about the environmental impacts of digital should be conducted worldwide, as is already the case in France. Such a large perspective would help estimate the benefits of all the ongoing efforts but also give insights on where more focus is needed.

Limitations and hypothesis

There are many ways to assess environmental impacts, but there are a few things to keep in mind:

- Most free tools only rely on transferred data, the number of HTTP requests, and DOM size. This is insufficient to capture the overconsumption related to animations, heavy calculations (especially using JS) but also benefits from dark mode. To achieve this, other metrics are needed, such as CPU/GPU, Energy, and RAM/memory usage should be measured.

- Tools usually stick to page loading and sometimes scrolling. This is not always relevant to real usage and often misses some obvious things, such as accepting cookies, client-side cache, playing videos, etc. Real user journeys should be measured, based on analytics and user feedback.

- GHG is often used as a proxy for environmental impacts, but this is not enough. To avoid impact transfers and greenwashing, other indicators should be used, as stated by the ADEME (PDF, French, 980 kB).

These notions are detailed in this article about the environmental impacts of web elements

Embedded environmental impact needs to be factored into our calculations. The web should not require users to update their devices every 2-3 years. We need to ensure that the lifespans of our digital infrastructure are extended.

Intersectional environmental issues

Sustainability ultimately involves people, as the planet will ultimately take care of itself. Building a just society that supports the needs of its people within the boundaries of its population is key. Throughout our lives, all of us require accommodation. Our ability to navigate the physical and digital world changes, and a sustainable economy supports that. One in five people has a permanent disability, and everyone will have both temporary and situational disabilities throughout their life. For more on this, you should read the Accessibility chapter.

In building sustainable digital interfaces, we must consider the user, including those with disabilities. Sustainable digital interfaces allow users to quickly navigate to accomplish their tasks. An inaccessible interface may ultimately require a user to take a less sustainable path to accomplish their goals.

Similarly, one must consider human diversity. Race, class, gender, and sexual identity have been used to divide people. A sustainable web should promote climate justice.

For further information, refer to:

Legal obligations and reporting standards

Digital sustainability is becoming a greater concern in the regulatory landscape. Recent legislative changes worldwide have introduced requirements that everyone must comply with.

Where organizations once faced minimal obligations, they are now confronted with new regulations designed to start accounting for their environmental impact. The urgency of the climate crisis has accelerated this shift, with governments increasingly holding businesses accountable for their ecological footprint.

The European Union currently leads the world in terms of sustainability regulation. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRSs) mandate that large corporations report on Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions annually, encompassing direct, indirect, and value chain emissions. Scope 1 covers direct greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions made by a business, Scope 2 covers indirect emissions from a business such as electricity to heat or cool a building, and Scope 3 covers all other emissions associated, not with the company directly, but that the organization is indirectly responsible for.

Meanwhile, the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) and Energy Efficiency Directive focus on mandating physical infrastructure (such as data centers) and products towards circular economies and general sustainability principles. Furthermore, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D) mandates that organizations foster sustainable behavior relating to workplaces and employees.

Additionally, The Green Claims Directive explicitly legislates around claims of sustainability or related terms (such as being green) to fight against greenwashing. The Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) mandates the sustainability of operations relating to DevOps activities. The EU Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act provides necessary regulation around Artificial Intelligence and the environmental impact of such technologies.

It should be noted that many of these European Union laws apply to both citizens and residents of the EU. This also applies to companies who do business with Members of the EU or with people living within the EU. Like the GDPR, the ramifications of these laws have global significance.

Two best practice repositories from the EU known as the Handbook of Sustainable Design of Digital Services (GR491) and the European Digital Rights and Principles have become widely associated with their legislative move towards sustainability.

France established itself as an early leader in digital sustainability through the publication of its REEN legislation alongside the General Policy Framework for the Ecodesign of Digital Services (RGESN). This framework provides clear and actionable guidance on best practices, setting a high standard for sustainable digital service design. There is a huge focus on training engineers on how to build more energy-efficient digital products/services. With its circular economy anti-waste law AGEC also in effect, and its other best practice AFNOR Spec 2201 also available, the country is working hard to tackle environmental issues.

In Germany, progress is also being made regarding sustainability through the development of the Energy Efficiency Act (EnEfG) which mandates that data centers use less energy on the grounds of climate protection, and the Supply Chain and Due Diligence Act (SCDDA) legislating on the human side of sustainability providing legal protections across supply chains.

California’s new emissions reporting law, the Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (S.B. 253) along with its sister legislation Climate-Related Financial Risk Act (CFRA), are a landmark regulation package with potential global ramifications. They will require companies with revenues exceeding $1 billion and business operations in California to disclose their greenhouse gas emissions. Given California’s role as a global hub for digital technology, these laws will likely influence practices and standards internationally, making it essential for digital agencies worldwide to take note.

India is the final country of note that has crafted sustainability legislation, in this case, the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR) which is much like the EU’s CSRD, except for those living or trading in this nation, enforcing reporting scope emissions.

Much like web accessibility, digital sustainability is becoming a non-negotiable aspect of doing business. Non-compliance with the emerging sustainability standards is no longer an option, and businesses face a range of potential penalties.

The regulations affecting digital sustainability are diverse. Some, like the CSRD, focus on enhancing transparency and accountability in emissions reporting, while others aim to prevent greenwashing by enforcing accurate and responsible communication about products and services.

Standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) provide essential frameworks to help digital agencies meet these new obligations. It may be helpful to think of laws to dictate what must be done, standards to provide the roadmap for compliance, and best practices to ensure that compliance is achieved effectively and ethically.

Digital professionals should look at what legislation, standards, and best practices for digital sustainability apply to them prior to the creation of their product or service and monitor any developments as their product evolves (to meet an evolving compliance landscape).

The benefits of adopting sustainable practices from the offset extend beyond mere compliance; they offer a competitive edge in a market increasingly driven by the need for excellent customer experience and increasing environmental considerations and can lead to time and cost savings when not having to be retrofitted into existing works. As this report outlines, integrating sustainability into your business strategy is not just about avoiding penalties, but about seizing new opportunities in a rapidly evolving landscape.

Organizations are beginning to add a /sustainability page to the footer of their webpage to allow them to report on their CO2 emissions as well as describe what they are doing to reduce emissions for their digital services.

For further information on specific regulations and standards, refer to:

- WSG: Web Sustainability Laws & Policies

- WSG: Draft Sustainable Tooling And Reporting (STAR) 1.0

- GRI: Global Reporting Initiative

- GR491, The Handbook of sustainable design of digital services | ISIT

- WERF: Web Ecodesign Reference Framework

- Apolitical: Keeping tech sustainable

Evaluating the environmental impact of websites

Evaluating the environmental impact of a website is everything but an easy task. It usually involves assessing the energy consumption and carbon footprint associated with its operation, from the servers that host it to the devices that access it. This evaluation considers various factors, including the efficiency of the hosting infrastructure, the amount of data transferred during page loads, the use of renewable versus non-renewable energy by data centers, and the overall optimization of the website’s code and assets. Websites that are heavy in images, videos, and other large files require more energy to load and transmit, contributing to higher carbon emissions. By understanding and optimizing these elements, website owners can reduce their digital carbon footprint, contributing to a more sustainable web and helping to minimize their environmental impact.

It is very important to keep in mind that there is still no available tool that would allow for precise measurement of every single part of the system, allowing for a nice overall sum. Therefore, we can measure isolated parts of the systems our teams work on or resources to the use of the models that allow us to do an estimation based on specific inputs. One model that is currently used in many different website carbon calculators and is being worked on and improved is the Sustainable Web Design Model. This model can be a slightly controversial way of estimating, as well as any currently out there. However, it has been present for a while, allowing comparison over time, and simplifying this complex process allows for better understanding and, hopefully, recognition of the problem itself.

Usually, we talk about CO2 but it would be more accurate to talk about eqCO2 or CO2e: values equivalent to CO2 emissions but rather applies to all kinds of greenhouse gasses (GHG). Also, other environmental impacts should be considered (as is the case in Life Cycle Assessment for instance) to avoid impact transfers (e.g. when reducing GHG emissions proves detrimental to water consumption) and debatable claims such as “carbon neutrality”.

For further information, refer to:

A quick note on assessing environmental impacts

The queries from last year have been updated to reflect the new data structure. For most, there has been no effective difference in the results.

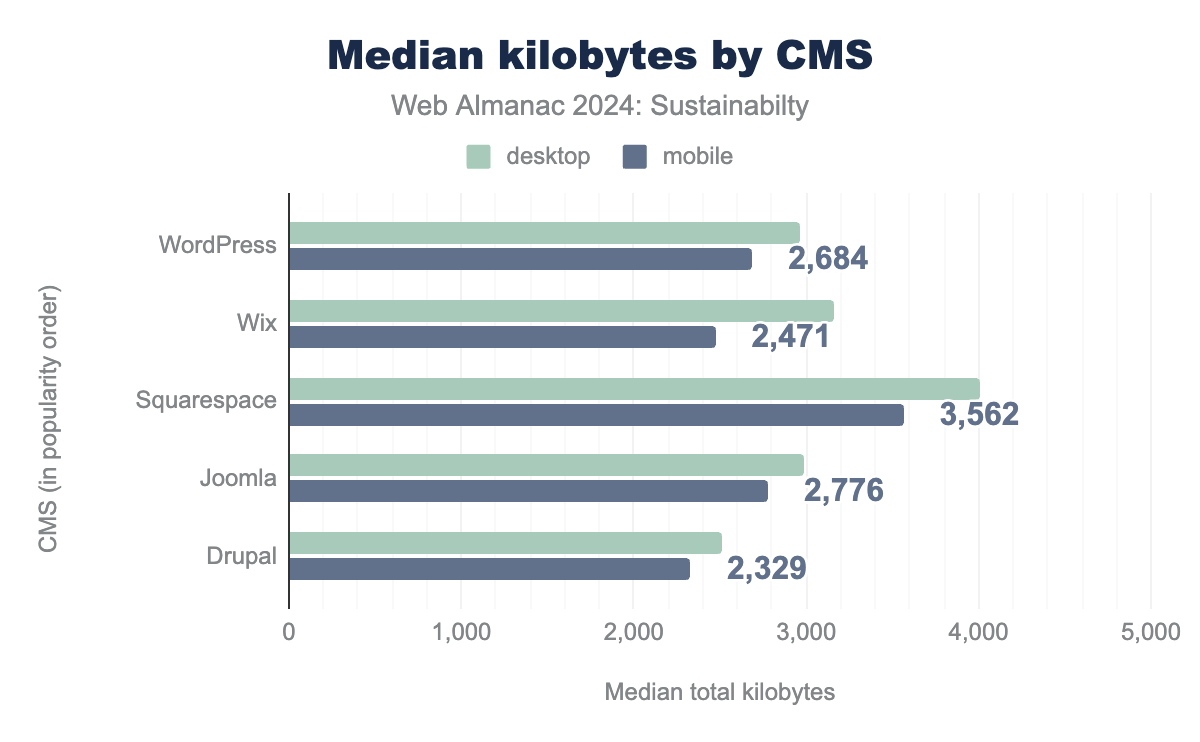

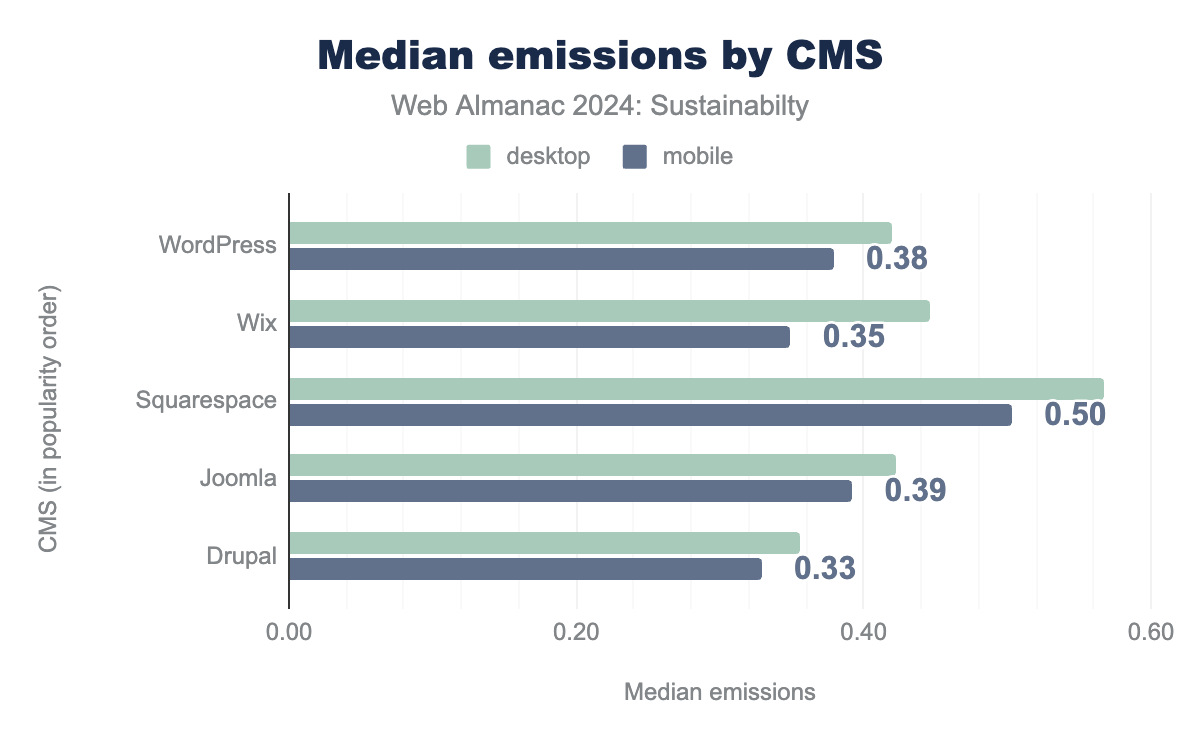

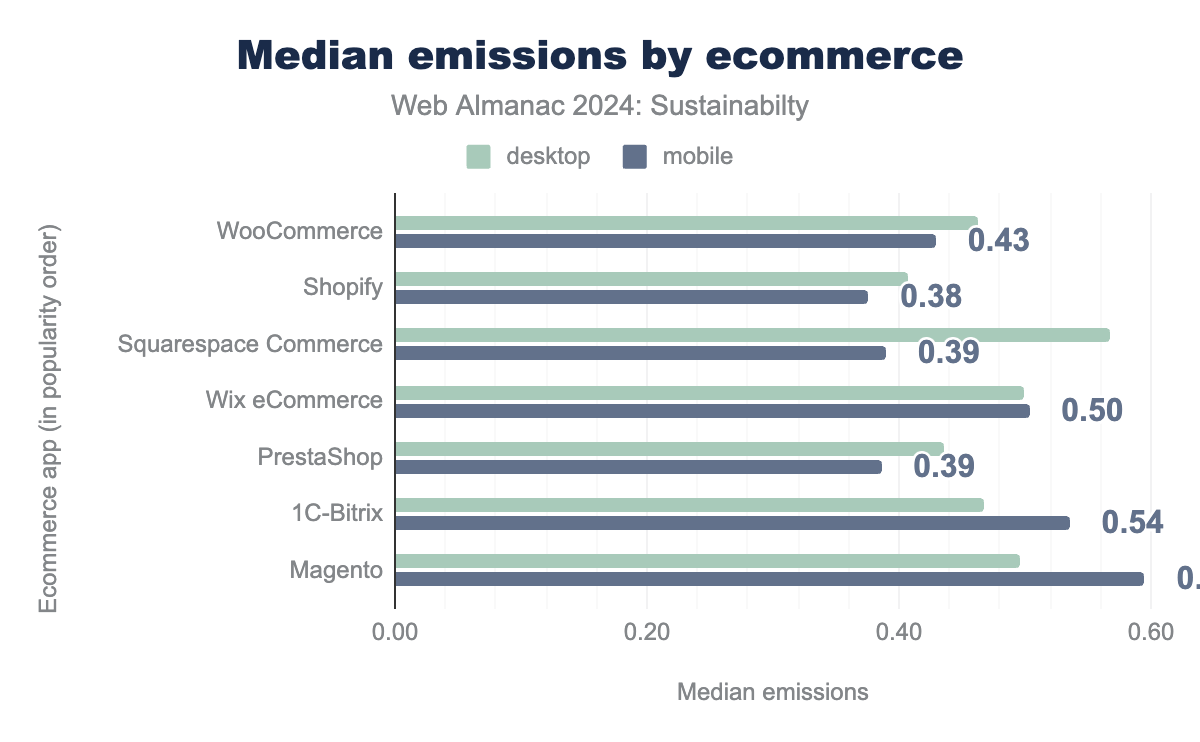

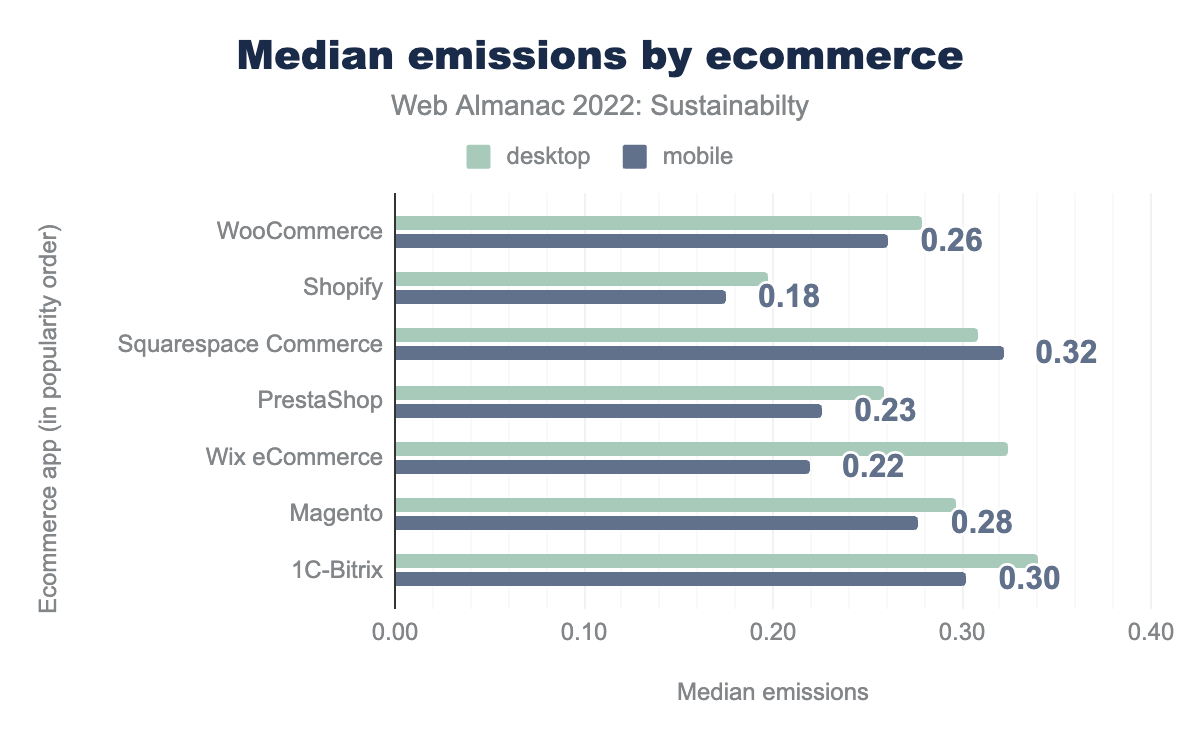

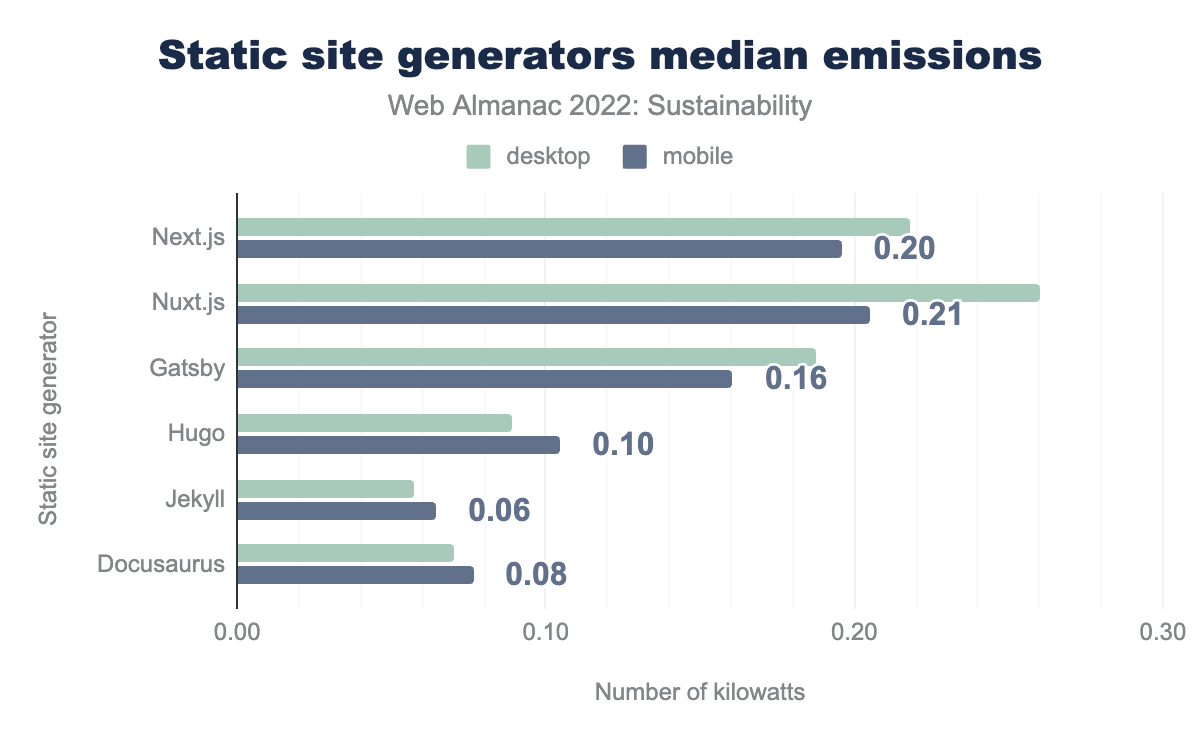

The update of the CO2 emissions calculations is reflected in the global page, SSG, CMS, and e-commerce emissions calculation. We have updated the calculations to the version 4 model of emissions calculation based on Sustainable Web Design Model.

Main differences:

- The global carbon intensity has changed from 442g/kWh to 494g/kWh.

- Previously the website CO2 per visit was a ’simple’ equation considering the page weight (data transferred in GB), multiplied by the estimated energy usage of loading one GB (0,81) and multiplying it with the carbon intensity.

- In the updated formula segments the energy consumption by data centers, network, and energy consumed by user devices for greater insight.

-

Each system segment is further broken down into two categories — operational and embodied emissions.

- Operational: The emissions attributed to the use of the devices in a segment.

- Embodied: The emissions attributed to the production of the devices in a segment.

- Each segment is attributed a certain weight in the calculation reflecting its estimated contribution to the total emissions -> for example, each segment has its estimated carbon intensity for both operation and embodied energy consumption.

- At the end, this allows us to estimate this for each segment, and then sum the totals to get the total estimated emissions.

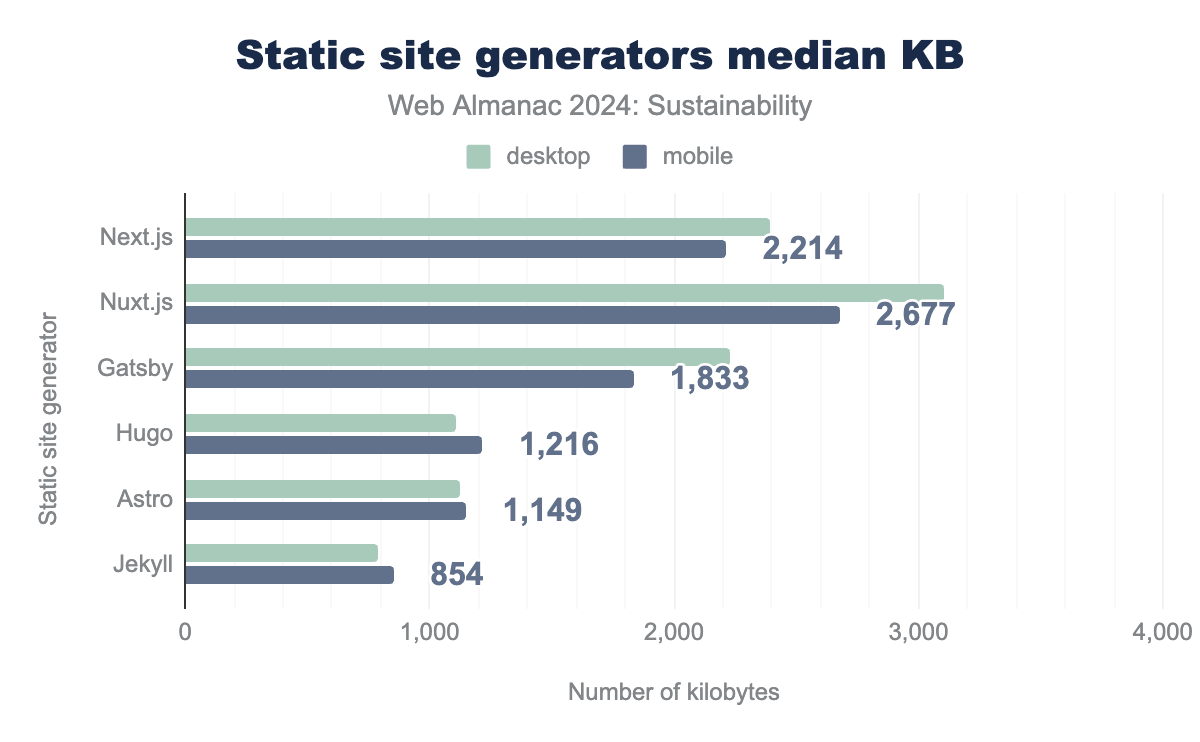

Page weight

The Sustainable Web Design Model uses data transfer as a proxy. While we can debate whether this input gives us an accurate carbon emission estimate, it’s clear that the increasing bloat of websites over the years is contributing to the problem. More data needs more servers to store them, more energy to deliver them, and more processing power to display them on-screen to end users. Over the years, there has been a visible upward trend, so let’s look at that data for 2024.

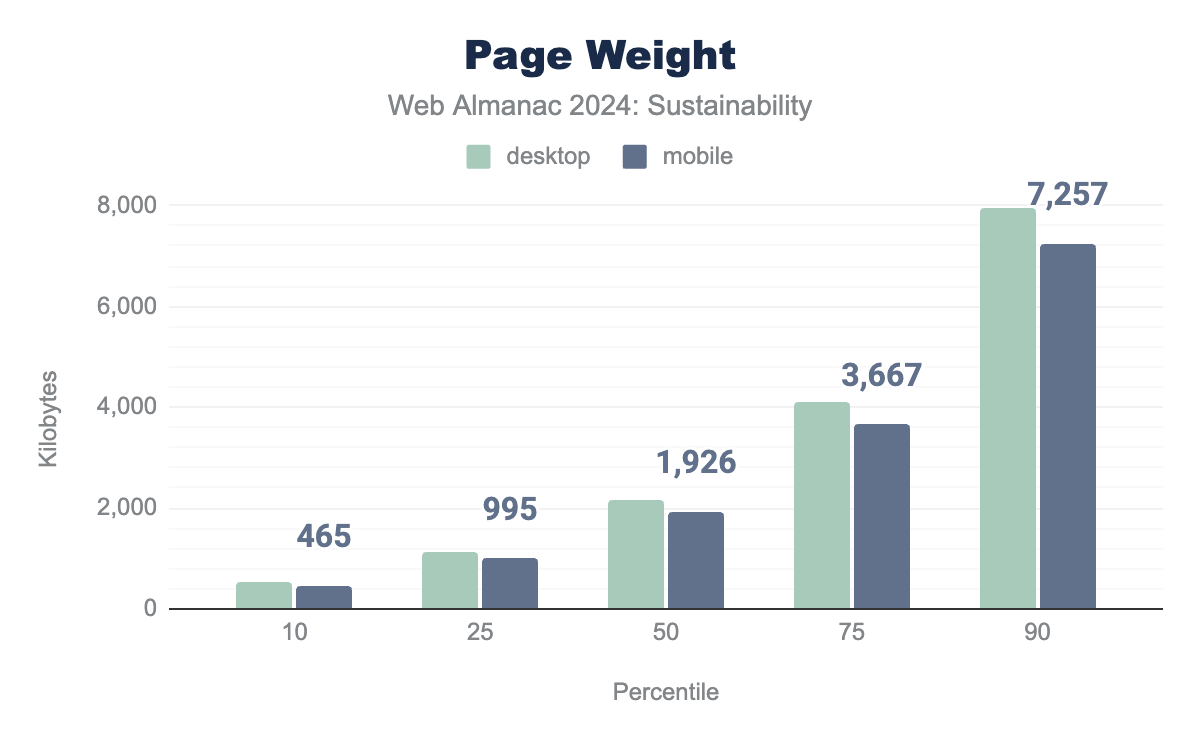

Page weight represents the amount of data transferred to access the web page (based only on HTTP requests). It is recommended that this metric be kept as low as possible to ensure a fast load and good user experience for all users. On the 90th percentile, the average mobile site weighs around 7.2 MB, while desktop ones are around 8 MB. The good news is that these numbers are slightly lower than the ones in the 2022 Almanac. The bad news is that these numbers are still way too high. When we talk about sustainability, we usually touch upon inclusion, and to make sure the majority of Internet users can access the page and have a decent user experience, page weight should be kept below 1MB, ideally around 500KB.

It is also important to emphasize that these numbers are coming for a so-called lab test, meaning that pages were accessed via script and not real users. With many websites these days implementing lazy loading strategies (request and load assets once they are needed, through native lazy-loading for images and iframes or progressive hydration for dynamic components), as well as loading and processing extra scripts once the user has given consent for it (and the script does not include any user interaction emulation), average page weight is sure to be an even bigger number.

For further information, refer to:

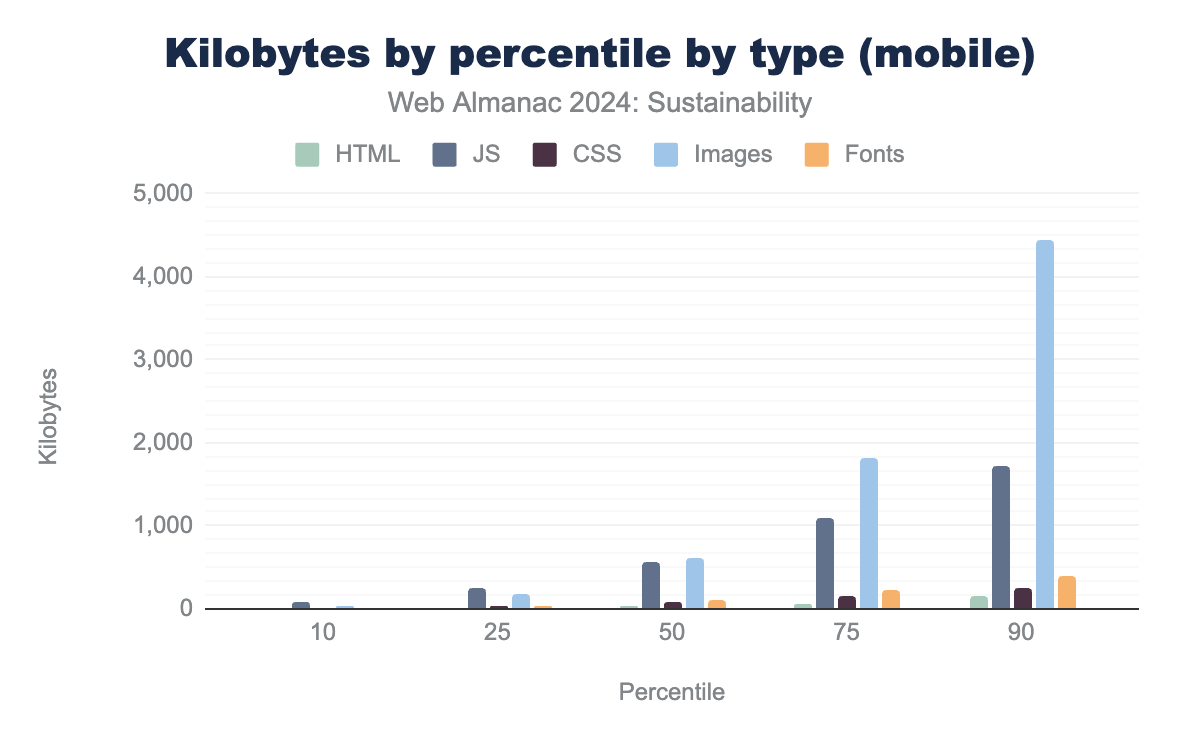

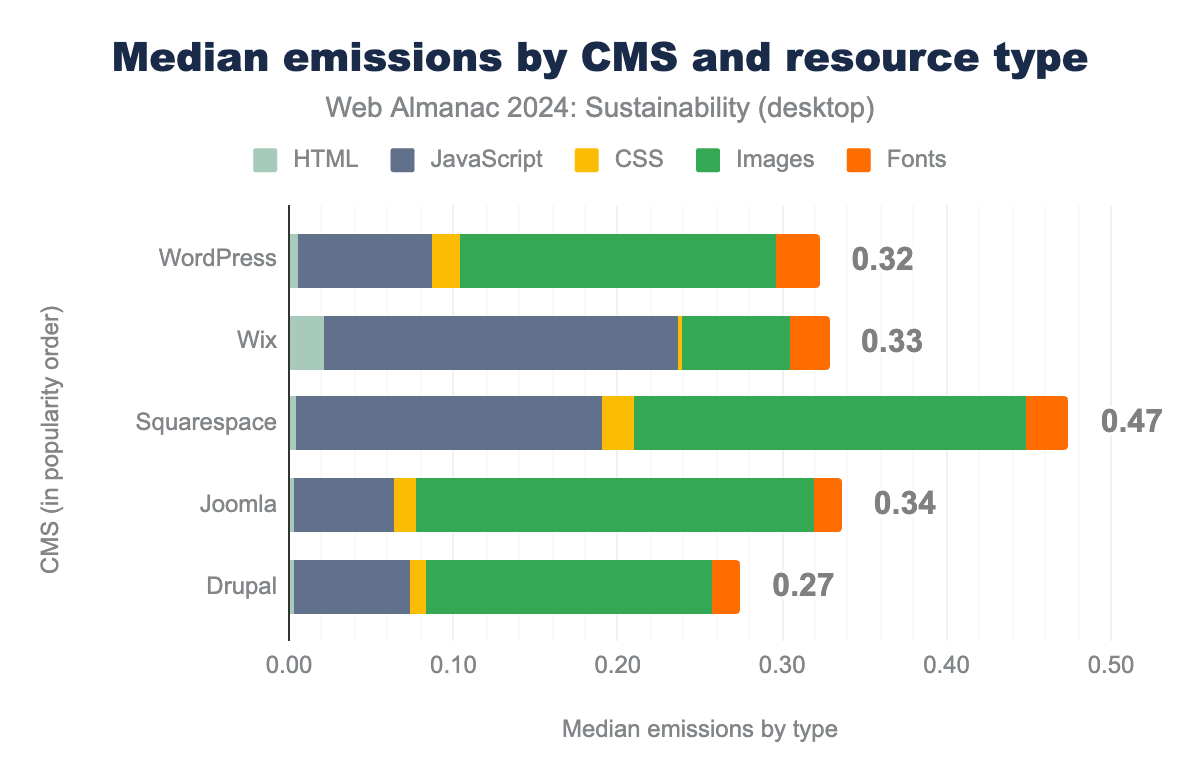

Weight by content type

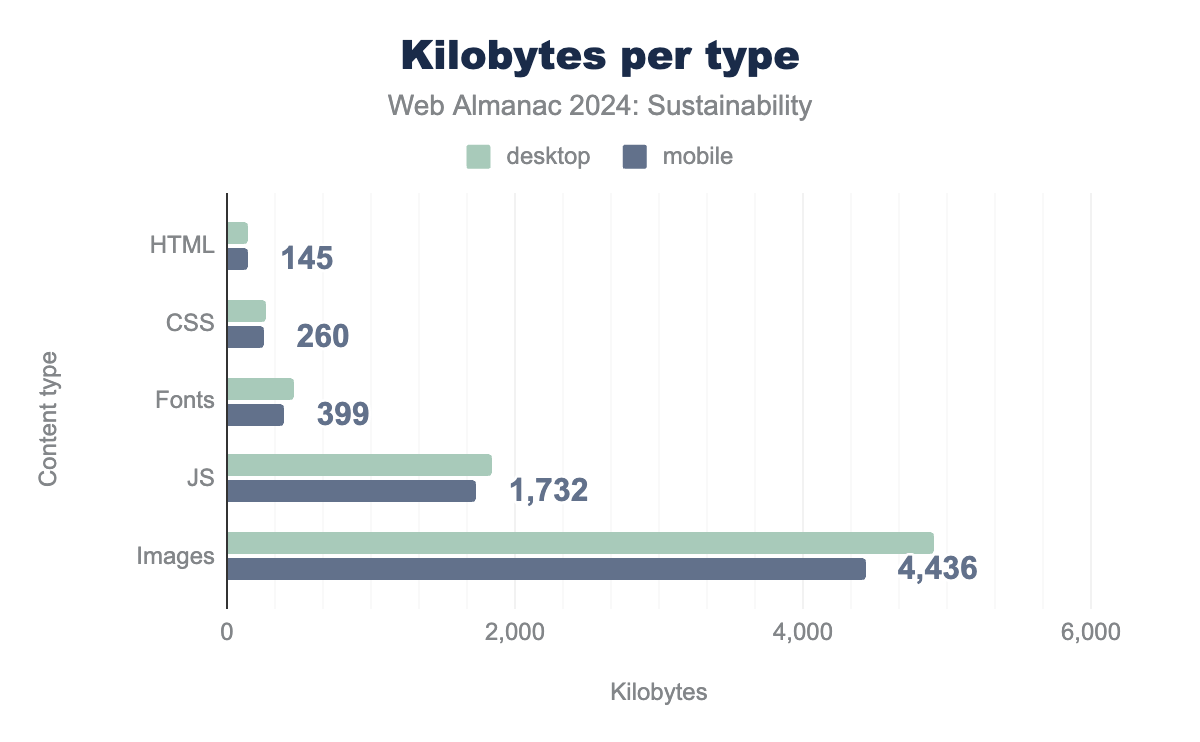

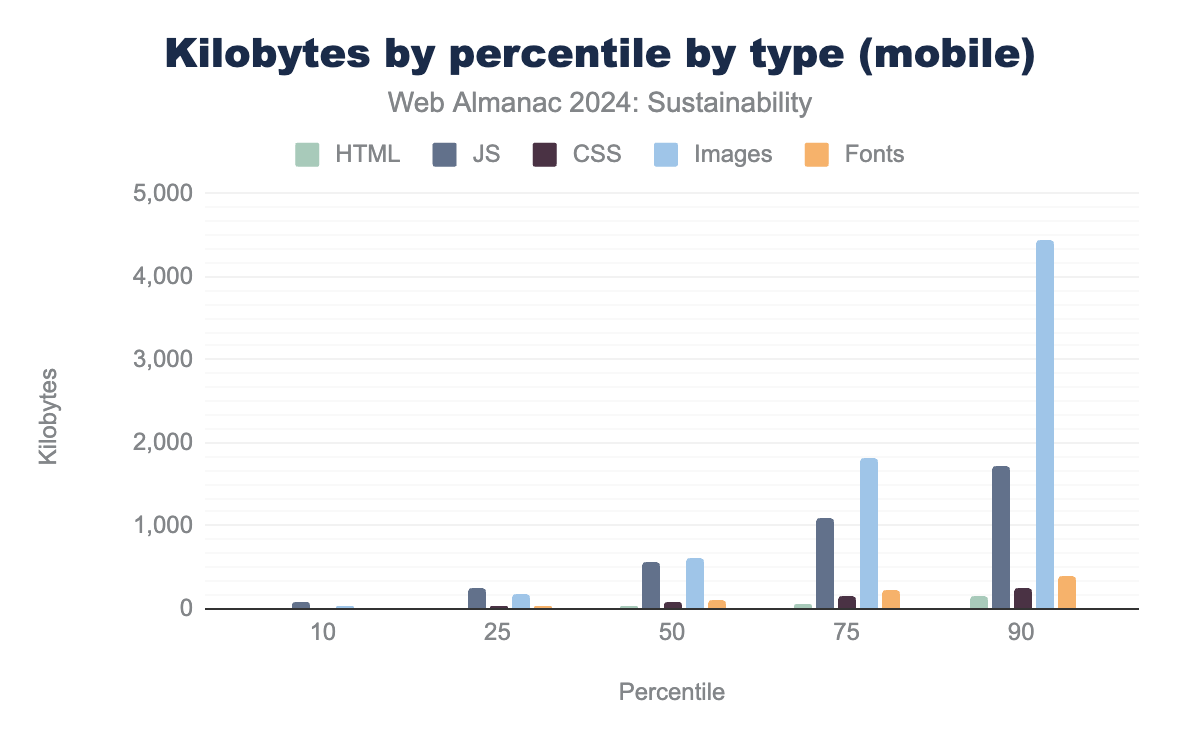

With data showing that an average page weighs around 8MB, the next logical question is where all those kilobytes are coming from. Modern pages are composed of many different pieces, including basic building blocks such as HTML, CSS, and JS, as well as fonts and images to enhance visual presentation.

From the 90th percentile of collected data, it is clear that the largest portion, more than half of the page’s total weight, belongs to images. This is quite an expected result and one of the parts where small optimizations can have the biggest impact. Slightly surprising and worrying is that there is still a very small gap between desktop and mobile numbers, not only in images but across all types. This shows us that even though mobile-first became a concept over 15 years ago, most teams still don’t optimize their mobile sites to account for the limitations of mobile networks, phone plans, and smaller screens (for which smaller images are usually enough). In the end, it may look mobile-friendly, but the experience isn’t.

It is also not surprising that the second largest portion is JavaScript code. Modern frameworks, dependencies, packages, as well as legacy code easily accumulate a larger amount of JavaScript code. The biggest problem is that script processing is part of the page loading that needs the most power from the CPU and consumes the most energy. Also, security should be a concern, check the Security chapter for more on this.

Compared to images and JavaScript, the weight of CSS doesn’t look too large. However, the important question covered later in the chapter is how much of this code, both CSS and JS, is actually being used. In addition to these considerations, the processing cost of such code should be considered (CPU/Memory usage).

The size of font files may look reasonable if we consider that a typical custom font file can be over 200 KB. This size, though, can be brought down significantly by subsetting font files to only characters that are needed for the site content. The median font file with an English-only subset of characters should be around 12 KB, which is 6% of the original 200 KB and could bring us closer to having a great-looking page that is below 1 MB.

More about this topic can be found in the Fonts and Page Weight Chapter.

For further information, refer to:

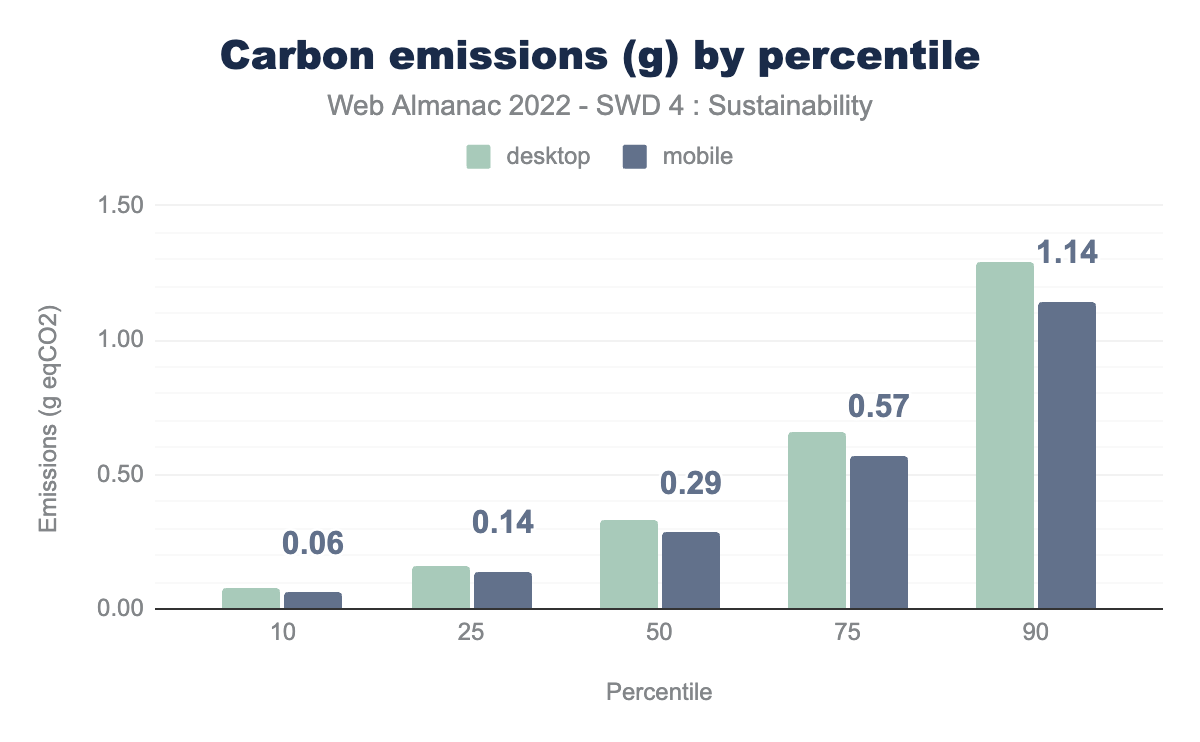

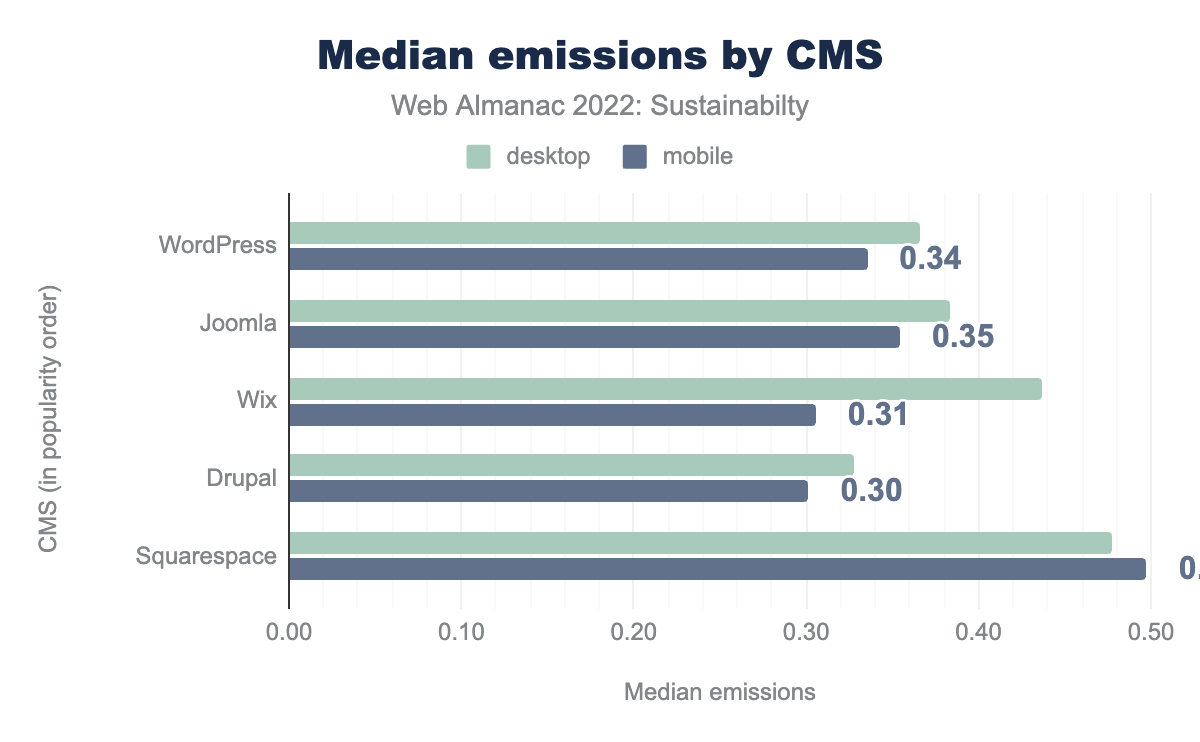

Carbon emissions

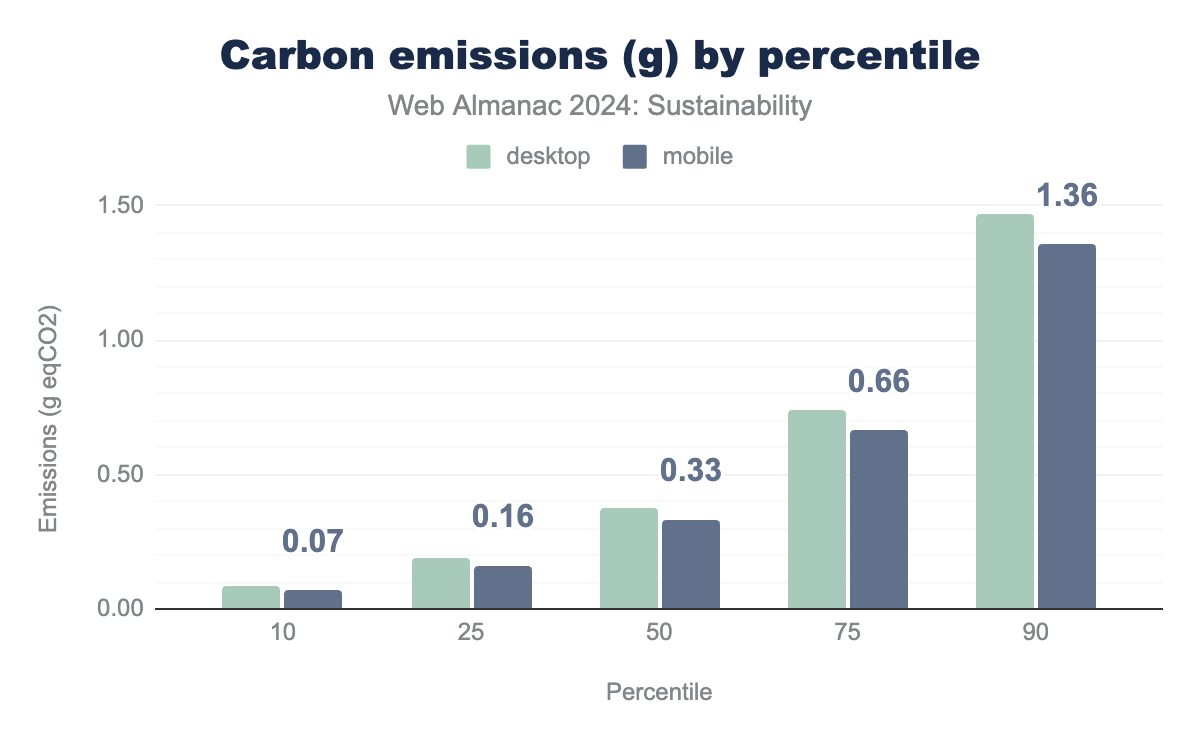

As stated above, back in 2022, we used the Sustainable Web Design (SWD) model to estimate carbon emissions based on page weight. As we explained many times, this is inaccurate but constantly improving. As such a new version of the model was recently published. This has a considerable impact on the results so we decided to recalculate emissions from the 2022 data before proceeding with the 2024 data. In both cases, we exclude data from the 100 percentile, which is some kind of “worst-case scenario” and way above other percentiles thus making the diagrams less readable.

Emissions for 2022

Based on the V4 of the SWD model, we get these global results for emissions:

If you take a look at the results from the 2022 Sustainability chapter, you’ll notice that these new estimations are slightly lower. This is why we recalculated them. Otherwise, we could have been led to think that emissions from web pages diminished significantly between 2022 and 2024 (spoiler: this is not the case). With this in mind, we can now look at the data for 2024.

Emissions for 2024

Based on the SWD V4 model, carbon emissions for web pages in 2024 are as follows:

Even if the results are quite similar to those from 2022, we notice a slight increase in carbon emissions, which is even more significant for the 75 and 90 percentile. This is bad news as we should focus on reducing all our carbon emissions. This is not surprising since page weight has been globally on the rise for many years. More on this in the Page Weight chapter. The goal of the Sustainability chapter is precisely to raise awareness on this but also to provide recommendations to improve things.

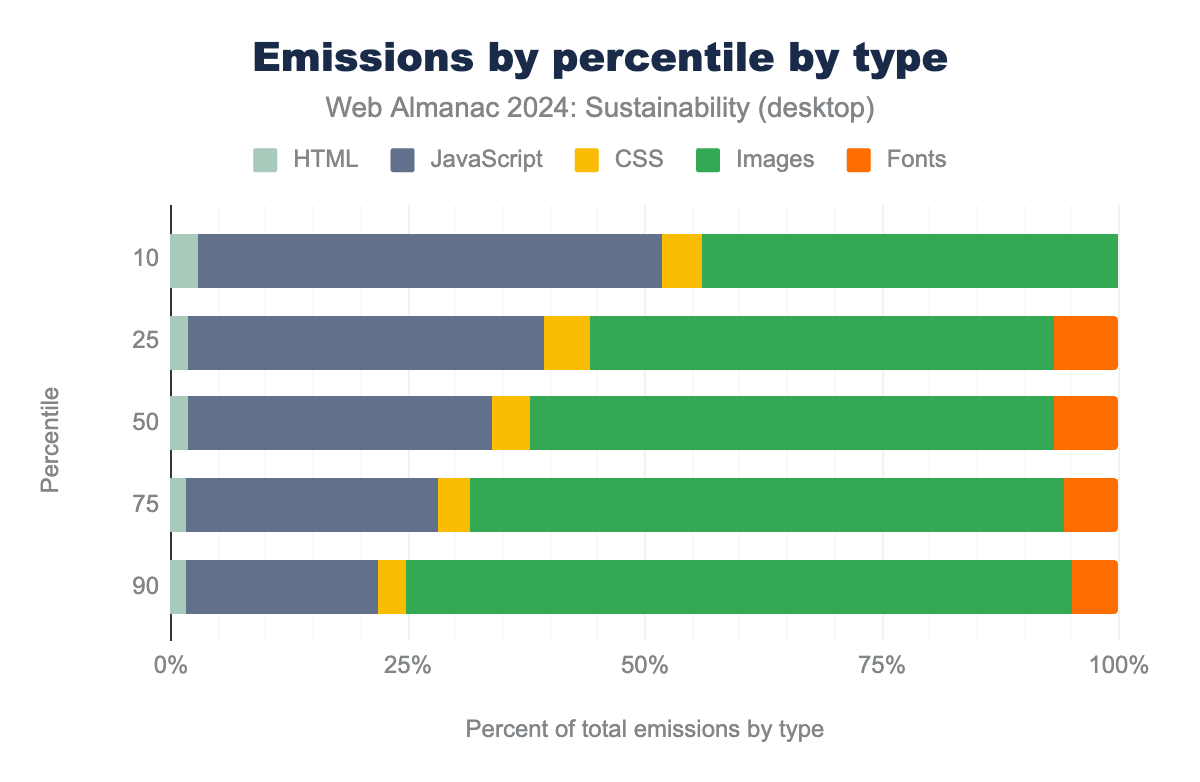

We can also take a look at the share of emissions for different resources (HTML/JS/CSS/images/fonts), distinguishing mobile and desktop:

This looks quite similar to what we found in 2022, leading to the same conclusions. We should however insist on the fact that images are usually easier to process than JS and CSS. Here, JS is a major offender regarding transferred data but is usually quite impactful on memory, CPU, and GPU, which then leads to additional environmental impacts that are not yet considered in the SWD model. For instance, soliciting more CPU/GPU/memory could have an impact on the battery discharge of your smartphone, thus forcing you to change the battery or device sooner than expected and possibly making the website less performant on older devices.

Some “meta” considerations

Somewhere along writing this chapter, someone in the team wondered what would be the total carbon emissions related to the HTTP Archive monthly crawl. Each month, data is collected from millions of web pages to monitor the state of the web. For instance, the Web Almanac is based on this data. Find more about the methodology.

Read other reports from the HTTP Archive.

We ran a query on the data collected for the 2024 Web Almanac and found that the total amount of transferred data would be around 201,66 TB. Using the SWD model, this would amount to 27,7 T CO2. Based on a CO2 converter, this is approximately as many carbon emissions as a thermal car driving for 127 298 km (going around the Earth for more than 3 times) or manufacturing 323 smartphones. Things only add up when considering this crawl is done monthly.

But you should also keep in mind that:

- This is a necessity to have updated data.

- Some of these pages gather millions of visits each month.

- That does not prevent us from thinking about ways to reduce these impacts (and I hope that will be considered soon).

Going further

It should be noted that while many assume sustainability to be a task primarily (or purely) focused on reducing carbon (GHG) emissions, the considerations of digital sustainability are not as simple as they would initially appear. There are not only several ways in which sustainability can be measured and a variety of different resource types that must be accounted for, but a range of variables that can impact the resulting calculation.

Carbon emissions can ultimately be measured through the amount of energy (electricity) consumed through the act of processing actions (such as how many objects are rendered to the screen and the energy intensity of CPU, GPU, and RAM required for this activity), and as such, it can be more easily calculated, and any reductions made where beneficial. However, other natural resources are consumed by Internet infrastructure or devices connected to the web such as water (for cooling equipment), materials and chemicals (e.g. printing), and e-waste (old devices being thrown away). The sustainability impact of these issues must also be accounted for in the lifecycle chain of a product or service.

For further information, refer to:

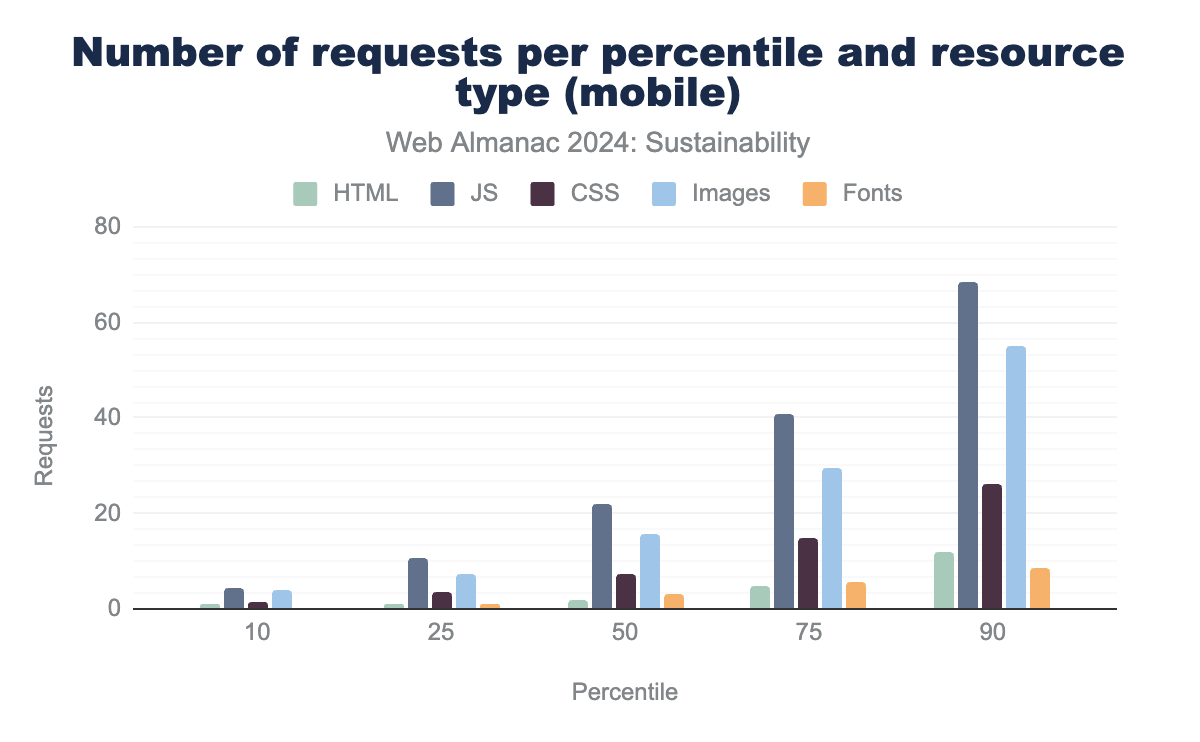

Number of requests

Requests are generated whenever a file is needed to load a page, providing insight into the page’s impact on the network and servers. They are even used to calculate environmental impact. Analyzing these requests helps us uncover opportunities for optimization, which will be valuable as we explore different types of assets and external requests.

It’s essential to minimize the number of requests. Setting an initial cap of 25 is a positive step, but it’s often challenging to meet this target due to the presence of trackers and similar elements.

From the extracted data, we can see that the number of requests is quite similar for mobile and desktop pages, which is not ideal. To respect mobile networks as well as plan limitations, it would be great to see fewer resources being loaded on mobile, which would result in fewer requests. The amount of requests, in general, is quite high, so let’s see what resources these requests are calling for.

The not-so-nice surprise here is that most of the requests, around 70 in the 90th percentile, are retrieving JS files, followed by over 50 for images. We can see that the pattern repeats itself across all the percentiles. This is very interesting since, in the report from 2022, the number of requests retrieving images was bigger than the ones retrieving JS. The follow-up question is whether the change in the number of requests also impacts the size of the retrieved assets. So, let’s check that.

The size of retrieved Images is almost double the size of retrieved JavaScript in the 90th percentile, so the “old” pattern is still there. This leads us to the conclusion that sites are loading fewer images but slightly heavier and, in general, more JavaScript, which is not a good trend since that leads to the need for more processing power and can exclude users with aging devices from accessing sites.

For further information, refer to:

More sustainable hosting

One of the simplest ways to reduce your carbon footprint is by choosing a sustainable hosting provider. Navigating this world can be quite tricky as no provider will truly be 100% carbon neutral as emissions always exist in some form, however, how they power their equipment, maintain their hardware, and deal with waste and redundancy can significantly impact the amount of emissions created. Therefore picking the right supplier can have a considerable impact on your ability to mitigate the emissions you produce.

One of the most critical features of a sustainable host is how they get their energy requirements. Hosts may get their electricity supply from normal power companies which in turn (depending on where they are located) generate a significant proportion of their energy from carbon-emitting coal or gas. Having a hosting provider that generates its energy requirements from solar, wind, tidal, and other natural sources will be more beneficial to the planet.

Other factors to consider are how the hosting provider cools its equipment. Many hosts require water cooling (and this can be an issue where freshwater can be a valuable limited resource), suppliers that use natural cooling in colder climates (for example) may be preferable.

Hosts that allow you to monitor your energy requirements (PUE, WUE, CUE) and even the amount of energy you are utilizing (CPU, GPU, RAM) on an active and logged basis can help you scale your hosting to reduce waste. If the host also recovers, recycles, and upcycles equipment rather than has a throwaway culture, this can reduce e-waste (the same goes for keeping equipment as long as possible).

Compensating for emissions at the server-side can be a complex task and transparency with hosting providers can also be a bit of a minefield, but providers are gradually becoming more sustainably minded and with specialist providers out there who can help you reduce your carbon footprint, taking steps to house your product or service in a greener space can be relatively straight forward.

For further information, refer to:

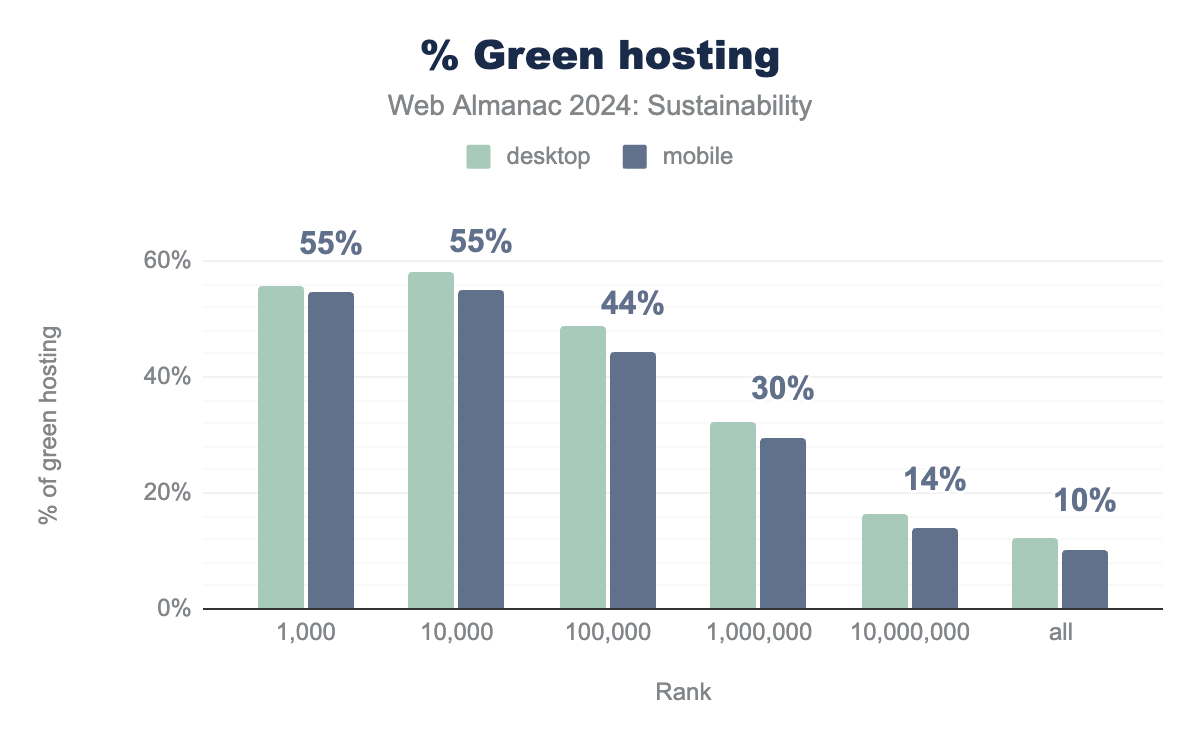

How many of the sites listed in the HTTP Archive run on green hosting?

To help organizations and individuals choose “greener” hosting, the Green Web Foundation maintains a dataset of providers matching the “green” criteria. With the list expanding and updating regularly it is not easy to track this metric, however, let’s see what is its current state.

We can see that only 14% of mobile sites, and slightly more desktop ones from the HTTP Archive are hosted using “green hosting” providers. That is a slight increase from 2022, when this number was 10%, however, it shows us that progress in this area is extremely slow and that there is still a long way to go in both aspects: encouraging website owners to switch to “greener” hosting provides, as well as more providers offering “greener” hosting.

There is a significant difference in top-ranked sites, showing that 55% of sites ranked in the top 10000 are considered to be hosted green. This number also has a slightly better jump from 2022, when it was 48% for the top 10000 ranked sites. As good as this may sound it can easily be attributed to the fact that many bigger hosting providers such as Amazon and Google are considered to be “green”.

Reducing the environmental impact of websites

Understanding the environmental impact of websites is only the first step; action is crucial. With our updated insights into website footprints, particularly regarding unused code and font usage, we can now explore more targeted and effective strategies for mitigation. Let’s examine how to translate this knowledge into tangible, sustainable web practices.

For further information, refer to:

Avoiding waste

Avoiding waste remains one of the most effective ways to reduce the environmental impact of websites.

- Minimize unnecessary content and code: Many websites still carry superfluous features and content. Be critical in assessing the necessity of each page element. Our analysis shows that unused CSS and JavaScript continue to be major contributors to page bloat. Ruthlessly eliminate unused code and unnecessary scripts.

- Optimize processing efficiency: JavaScript remains a significant source of energy consumption on user devices. Our data reveals a concerning trend of increased JavaScript usage. Whenever possible, opt for lighter alternatives or consider if the functionality is truly needed. Static HTML and CSS are often sufficient and far less resource-intensive.

- Prioritize lightweight assets: While text remains the most eco-friendly content type, our font analysis shows that even typography can contribute to waste. Choose the default system fonts where possible, and when using custom fonts, optimize their delivery. For images and videos, ensure they’re compressed and only loaded when necessary.

- Design for longevity and accessibility: Create websites that function well on older devices and slower connections. This approach not only reduces environmental impact but also improves accessibility. By supporting older technology, we encourage longer device lifespans, which is one of the most impactful ways to reduce digital environmental footprint.

- Implement smart loading strategies: Use techniques like lazy loading, code splitting, and conditional loading to ensure that assets are only delivered when they’re needed. This approach can significantly reduce unnecessary data transfer and processing.

Loading unused assets

You should only load assets that are essential for displaying the current view of the page. This can be achieved through techniques like lazy-loading, critical CSS extraction, and patterns such as Import on Interaction and Import on Visibility. It’s also crucial to load assets, particularly images and fonts, at the appropriate size for each client device. In this section, we’ll focus primarily on minimizing unused code and optimizing font loading, as our data shows these remain significant contributors to unnecessary page weight.

For further information, refer to:

Fonts

For optimal sustainability, system fonts remain the best choice, requiring no additional downloads. When custom fonts are necessary, consider these strategies to minimize environmental impact:

- Use the WOFF2 format for superior compression and broad support.

- Implement variable fonts to replace multiple font files with a single, versatile one.

- It would be nice to also use subsets or use a tool such as subfont.

- For custom fonts, use analysis tools to remove unnecessary glyphs or features.

- If using third-party font services, leverage their optimization options, but consider self-hosting for better control.

Remember, each additional font weight or style increases payload. Balance aesthetic needs with sustainability goals. For icons, consider Scalar Vector Graphics (SVG) instead of icon fonts for better efficiency and accessibility.

By thoughtfully approaching typography, we can create visually appealing websites while reducing data transfer and energy consumption.

For more detailed information, refer to our dedicated Fonts chapter and stay updated with the latest web font optimization practices.

For further information, refer to:

Unused CSS

The environmental impact of excess code extends beyond mere inefficiency. It directly translates to increased energy consumption and a larger carbon footprint for both servers and user devices. While CSS frameworks boost development efficiency, they often introduce substantial amounts of unused styles. This bloat not only affects page load times but also unnecessarily increases data transfer and processing requirements. In an era of ever-growing global internet usage, the cumulative effect of this excess code on energy consumption is significant.

Modern development tools have made identifying and eliminating unused CSS more accessible. Features like Chrome DevTools’ Coverage analysis offer powerful analysis to trim stylesheets. However, the practice of loading all CSS upfront for caching purposes presents a nuanced challenge. While it can reduce server requests and improve performance for returning visitors, it potentially increases the initial carbon cost of page loads.

As web applications grow in complexity, striking a balance between comprehensive styling and sustainable practices becomes increasingly crucial. Unused CSS not only impacts user experience through slower initial loads but also contributes to increased energy usage in rendering and processing. Addressing unused CSS stands out as a tangible step developers can take to reduce the digital ecosystem’s environmental impact.

Comparing the data from 2022 and 2024, we see some subtle changes. The 10th percentile remains unchanged, with no unnecessary CSS loaded, which is a positive sign but there’s a slight increase in unused CSS across the remaining other percentiles.

These changes, while small, suggest a general trend towards slightly larger CSS footprints. This could be attributed to the growing complexity of web applications, the adoption of more feature-rich CSS frameworks, or an increase in the use of CSS for advanced styling and animations. The data reveals that by the 90th percentile, websites are still loading over 200KB of unused CSS. This represents a significant amount of unnecessary data transfer and processing, which can impact both performance and sustainability.

Despite these small increases, the overall picture hasn’t changed dramatically since 2022. This suggests that while there have been some efforts to optimize CSS usage, there’s still considerable room for improvement, especially for websites with higher percentiles.

For further information, refer to:

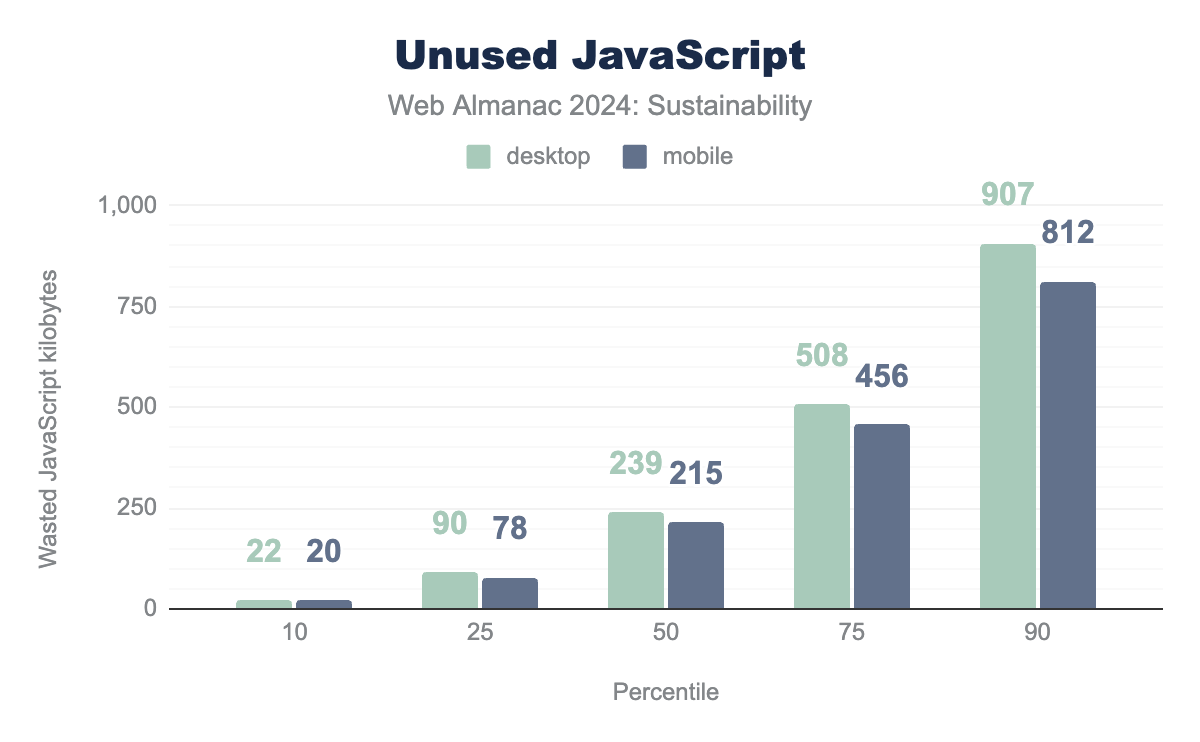

Unused JavaScript

Unused JavaScript significantly impacts energy consumption and carbon footprints of both servers and user devices. While JavaScript frameworks enhance development efficiency, they often introduce substantial unused code, affecting page load times and increasing data transfer unnecessarily.

Modern techniques like tree shaking and code splitting are crucial for optimizing JavaScript. The following steps will most probably help you to decrease your unused Javascript:

- Tree shaking eliminates dead code from the final bundle, particularly effective with ES6 modules.

- Code splitting breaks code into smaller chunks, loading only what’s necessary for the current functionality.

- Carefully evaluating the JavaScript libraries and frameworks.

- Regularly doing code audits and refactoring to get bundle sizes smaller.

Comparing 2022 and 2024 data reveals significant increases across all percentiles.

By the 90th percentile, websites now load over 900KB of unused JavaScript for desktop and over 800KB for mobile, significantly impacting performance and sustainability. The disappearance of 0KB values at the 10th percentile indicates even the most optimized sites now include some unused JavaScript.

The substantial increase in unused JavaScript between 2022 and 2024 underscores the urgent need for the web development community to adopt these optimization techniques for improved performance and sustainability.

For further information, refer to:

Other technical optimizations

Different resource types have different energy intensity levels and this should be taken into account when choosing what to include with your product or service. Syntax languages such as HTML and CSS [PDF] are fairly simple but must render each component to the screen (creating emissions).

CSS has the added complexity of simple state-based interactions that can develop additional emissions (due to repainting) such as animations and transitions. JavaScript being a more technical language also has rendering requirements that can accumulate as the build complexity increases. It can also be used both on the client and server-side and can develop impacts while interacting with the page (due to its ability to manage state).

All server-side languages (such as PHP) will also have an impact on resource utilization and energy efficiency [PDF] (based on performance). Images and media also have to be processed on the screen and due to their size and quality can be fairly impactful.

Optimizing your content

Now that we’ve examined the environmental impact of websites, particularly focusing on unused CSS, JavaScript, and font usage, let’s turn our attention to optimization. While removing unnecessary content and functionalities remains crucial, this year we’re emphasizing the importance of efficiency in what remains.

In this section, we’ll explore how to make your essential content as sustainable as possible. We’ll delve into optimizing images, videos, animations, and fonts - elements that significantly contribute to a website’s environmental footprint. By fine-tuning these components, we can substantially reduce resource consumption without compromising user experience.

For further information, refer to:

Mobile-first design

Adopting a mobile-first approach not only enhances user experience but also offers significant sustainability benefits. By prioritizing essential content and functionality for mobile devices, we naturally create leaner, more efficient websites that consume less energy and bandwidth across all platforms.

This approach encourages developers to critically evaluate each element’s necessity, leading to reduced data transfer and processing requirements. However, it’s crucial to ensure that this doesn’t result in multiple, device-specific versions of your site, which could potentially increase overall resource consumption.

When implemented thoughtfully, mobile-first design can lead to faster load times, lower energy consumption, and a smaller carbon footprint for your digital presence. It aligns well with other sustainability practices like minimizing unused code and optimizing assets.

For more detailed insights on how mobile-first impacts website performance, refer to our Performance chapter.

For further information, refer to:

Image optimization

Images remain a significant contributor to web page weight and energy consumption.

Optimizing images offers substantial sustainability benefits: Reduced data transfer, lowering energy use in data centers and network infrastructure. Decreased processing requirements on user devices possibly result in lower energy consumption. Faster load times, potentially reducing user wait time and associated energy consumption.

When implementing image optimization, balance file size reduction with maintaining necessary quality. Utilize modern formats, responsive loading techniques, and appropriate compression levels. For detailed performance implications and technical implementations of image optimization strategies, refer to our Performance chapter.

For further information, refer to:

Format (WebP/AVIF)

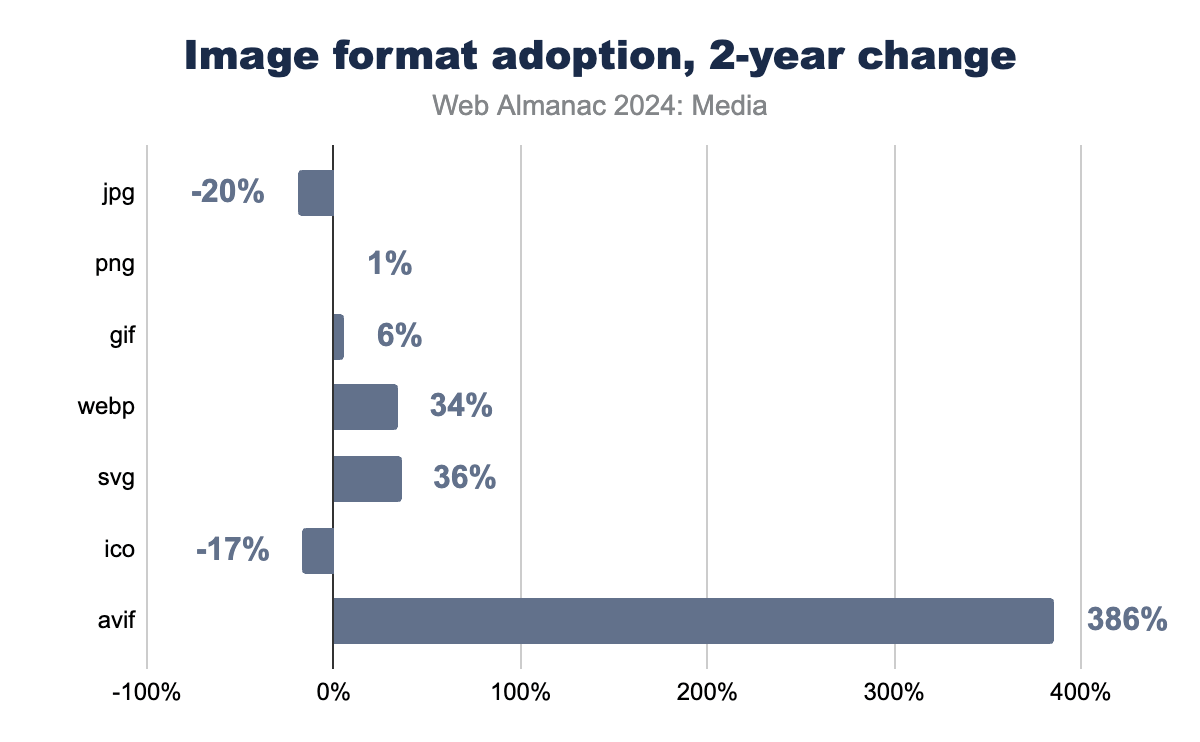

The adoption of modern image formats continues to be a crucial factor in web sustainability. WebP, with its impressive compression and wide browser support, remains a go-to format for optimizing images. Meanwhile, AVIF is gaining traction, offering even better compression in many cases. Let’s look at how the usage of these formats has changed from 2022 to 2024:

This data shows the evolving landscape of image format adoption. WebP has grown significantly, with a 34% increase in usage. Although AVIF shows an impressive 386% increase, it can be misleading since for desktop clients the usage of AVIF format is only at 1.40%, and for mobile clients 1.05%. Traditional formats like JPEG are seeing a decline, while PNG and GIF usage remains relatively stable. Current statistics for 2024 provide a clearer picture of where we stand:

Despite the clear benefits, many websites have yet to fully embrace these modern formats. The potential for reducing page weight and improving loading times remains significant. For optimal sustainability:

- Use WebP as your primary format, falling back to JPEG or PNG for older browsers.

- Consider implementing AVIF for browsers that support it (with a fallback), as it often provides superior compression.

- For icons and simple graphics, optimized SVG remains the best choice. Consider inlining frequently used SVGs directly in your HTML to reduce HTTP requests.

- For JPEG/WebP you can aim for 80-85% quality; adjust based on visual inspection.

- Use srcset and sizes attributes to serve appropriate image sizes.

- Lazy load non-critical images. Use

loading="lazy"(native HTML attribute) for images below the fold. - Strip metadata. Remove unnecessary EXIF data to reduce file size (thus also avoiding potential privacy issues).

- Implement a content negotiation strategy to serve the most efficient format based on browser capabilities.

- Periodically review and re-optimize images as new techniques emerge.

Remember, while adopting these formats can significantly reduce data transfer and processing requirements, it’s crucial to balance compression with maintaining necessary image quality. Over-compression can lead to degraded user experience and potential re-uploads, negating some of the sustainability benefits.

For more detailed information on implementing these formats and their performance implications, refer to our Performance chapter.

Responsiveness, size, and quality

As the diversity of devices accessing the web continues to grow, delivering appropriately sized images remains crucial for both performance and sustainability. Responsive image techniques allow us to serve optimized images for each scenario, reducing unnecessary data transfer and processing. It’s worth remembering that image quality doesn’t always need to be at maximum.

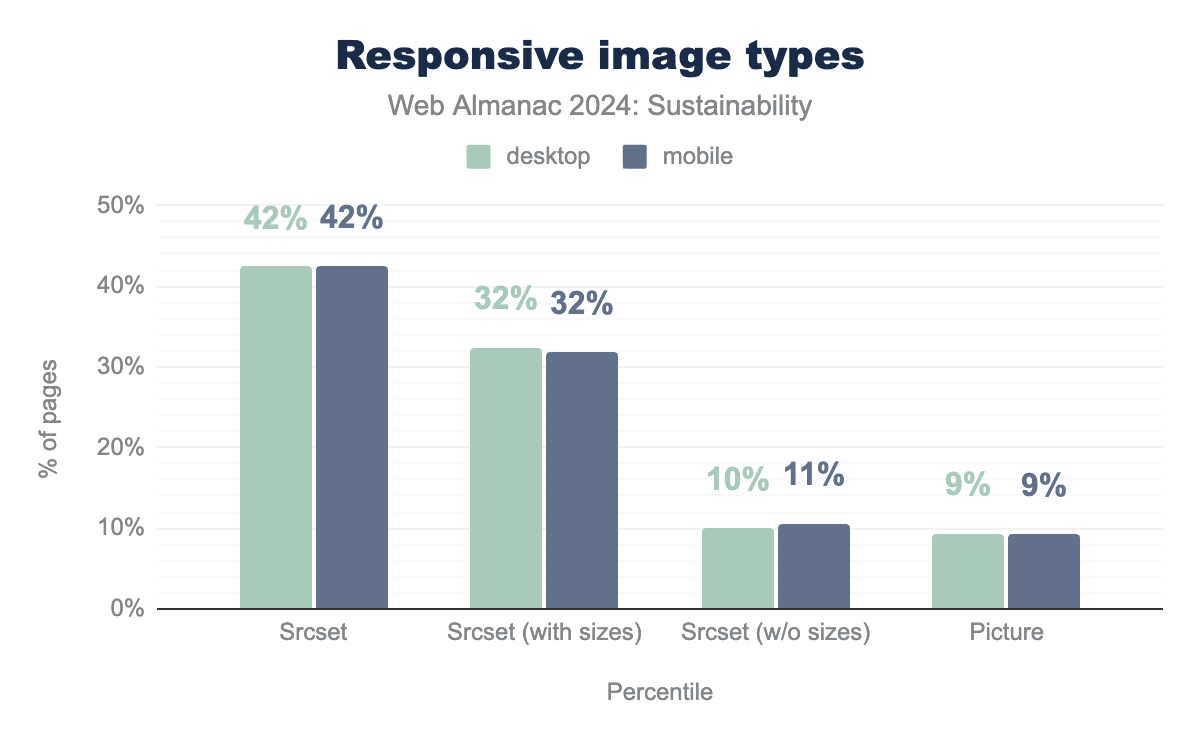

The data shows encouraging progress in the adoption of responsive image techniques:

- Overall usage of the

srcsetattribute has increased significantly, from about 33-34% in 2022 to 42% in 2024 across both desktop and mobile. - The use of

srcsetwith thesizesattribute, which provides more precise control over image selection, has also grown from around 25-26% to 32%. - There’s a slight increase in the use of

srcsetwithoutsizes, which, while not ideal, still offers some responsiveness benefits. - Usage of the

<picture>element has seen a modest increase from 8% to around 9.3% across both desktop and mobile.

This trend indicates a growing awareness among developers about the importance of responsive images. However, there’s still considerable room for improvement, as less than half of websites are currently utilizing these techniques.

To optimize your images for sustainability:

- Implement

srcsetandsizesattributes to serve appropriately sized images for different viewport sizes. - Use the

<picture>element for art direction and to serve modern formats like WebP and AVIF with appropriate fallbacks. - Optimize image quality, aiming for the sweet spot of size reduction without noticeable quality loss.

- Consider implementing automated tools in your build process to generate and optimize responsive images.

While the trend is positive, there’s still a long way to go before responsive images become ubiquitous. As web professionals, we should continue to advocate for and implement these techniques to create more sustainable and performant websites. For more detailed implementation strategies and performance impacts, refer to our Performance chapter and Media chapter.

Lazy-loading

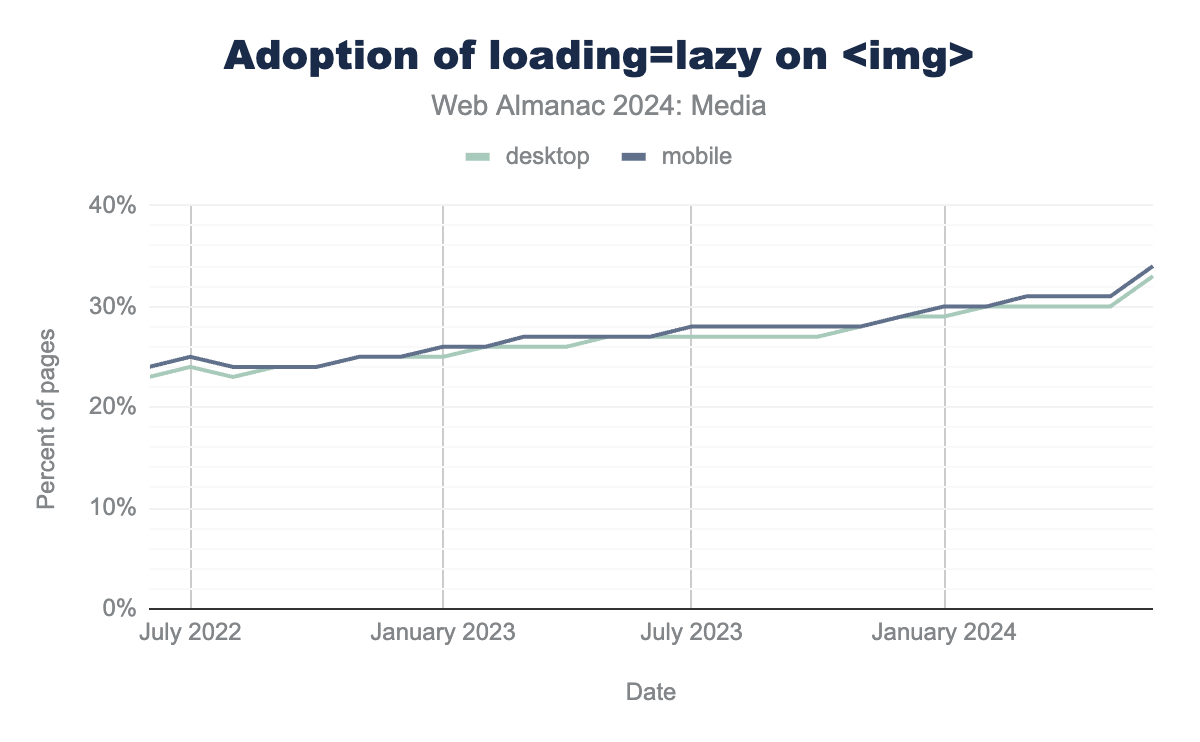

Lazy-loading remains a crucial technique for enhancing both performance and sustainability in web development. By loading images progressively we can significantly reduce initial page load times and unnecessary data transfer. This approach is particularly beneficial for sustainability, as it prevents the loading of images that users may never see, saving energy and resources.

<img>.

The past two year’s data reflects a growing awareness of the importance of optimized image loading. However, there’s still considerable room for improvement, as a significant portion of websites have yet to implement any form of lazy-loading. Regarding iframes, the advice remains largely unchanged:

- Native lazy-loading can be applied to iframes, offering similar benefits as with images.

- However, for optimal sustainability, consider avoiding iframes altogether when possible. Usage of iframes can lead to unnecessary resource consumption if overused or if embedded content isn’t controlled or optimized (e.g., third-party trackers or ads).

- The facade pattern remains a preferred approach for integrating external content like embedded videos or interactive maps.

For deeper insights & analysis, refer to our Performance chapter and Media chapter.

Efficiently encoding images

Image encoding plays a crucial role in web sustainability, directly impacting the amount of data transferred across networks and the energy consumed in the process. Efficient encoding reduces the size of images, which often constitute a large portion of a web page’s total size. This reduction in data transfer translates to lower energy consumption in data centers, network infrastructure, and user devices. Moreover, smaller, well-encoded images require less processing power to decode and render.

The cumulative effect of efficient image encoding across billions of web pages can lead to substantial global energy savings.

Video

Videos remain among the most resource-intensive elements on websites, significantly impacting sustainability. For more detailed information, refer to our Media chapter. When incorporating third-party videos, utilizing facades is still the recommended approach.

Additionally, configure your videos thoughtfully:

- Avoid preloading and autoplay to reduce unnecessary data transfer.

- Implement lazy loading for videos below the fold.

- Use appropriate compression techniques to reduce file sizes without compromising quality.

- Consider using adaptive bitrate streaming for varying network conditions.

Remember, every optimization in video delivery can lead to substantial energy savings given the large file sizes involved. Balancing video quality with sustainability goals is key to creating engaging yet environmentally responsible web experiences.

For further information, refer to:

Preload

Automatically preloading videos is a concern for web sustainability. This practice involves retrieving data that might not be useful for all users, potentially leading to unnecessary data transfer and energy consumption, especially on pages with high traffic volumes. From a sustainability perspective, preloading should ideally be avoided or only initiated upon user interaction.

Comparing the usage of the preload attribute between 2022 and 2024, we observe some changes. The percentage of websites not using preload has slightly decreased, from 58% to 55% on desktop and from 60% to 56% on mobile. This shift suggests a small increase in the use of preload attributes, which could have implications for sustainability.

It’s important to remember that the preload attribute only has three valid values: none, auto, and metadata (default). Using the preload attribute with no value or an incorrect value may be interpreted as ’metadata’, which can still involve loading up to 3% of the video to retrieve metadata. From a sustainability standpoint, ’none’ remains the most environmentally friendly option.

The slight increase in the use of ’metadata’ and the decrease in non-use of preload suggest that more attention needs to be paid to video preloading practices to enhance web sustainability.

For more detailed information on this topic, refer to Steve Souders’ 2013 article and the web.dev 2017 article on video preloading strategies.

Autoplay

The considerations surrounding autoplay continue to be critical from a sustainability perspective. Autoplaying videos consume data and energy for content that users might not be interested in viewing, potentially leading to unnecessary resource usage.

It’s important to note that the autoplay attribute can override preload settings, as autoplaying naturally requires loading the video content. This forced loading further impacts data consumption and energy use.

autoplay value on 6% of desktop videos and 6% of mobile videos. It is used with an value TRUE on 2% of desktop videos and 3% of mobile videos.Comparing the usage of autoplay between 2022 and 2024, we see some notable changes. The percentage of websites explicitly not using autoplay has decreased, from 53% to 45% on desktop and from 53% to 45% on mobile. This could be a concern for sustainability efforts. Also, we notice a slight increase for websites using an empty value for this attribute, which also triggers autoplay (and is bad for sustainability).

It’s crucial to remember that autoplay is a Boolean attribute, meaning its presence, even with an empty value, triggers autoplay behavior. The combined percentage of explicit autoplay usage (including autoplay, TRUE and other values) has remained relatively stable, around 8% for both desktop and mobile.

Given the sustainability implications, the trend towards more potential autoplay usage (through empty values) is worrying. Developers should be cautious about including the autoplay attribute, even if unintentionally, as it can lead to unnecessary data consumption and energy use. From a sustainability perspective, avoiding autoplay remains a recommended practice in most cases to reduce unnecessary data transfer and processing.

Animations

Animations continue to be a double-edged sword in web design. While they can enhance user experience, they pose challenges for both accessibility (more on this in the Accessibility chapter) and sustainability.

From a sustainability perspective, animations can be resource-intensive:

- They increase battery consumption and CPU/GPU usage, potentially reducing device longevity, especially on mobile devices.

- Animations often require additional code, which can delay rendering and increase page weight.

- Poorly optimized animations can lead to unnecessary repaints and reflows, further taxing device resources.

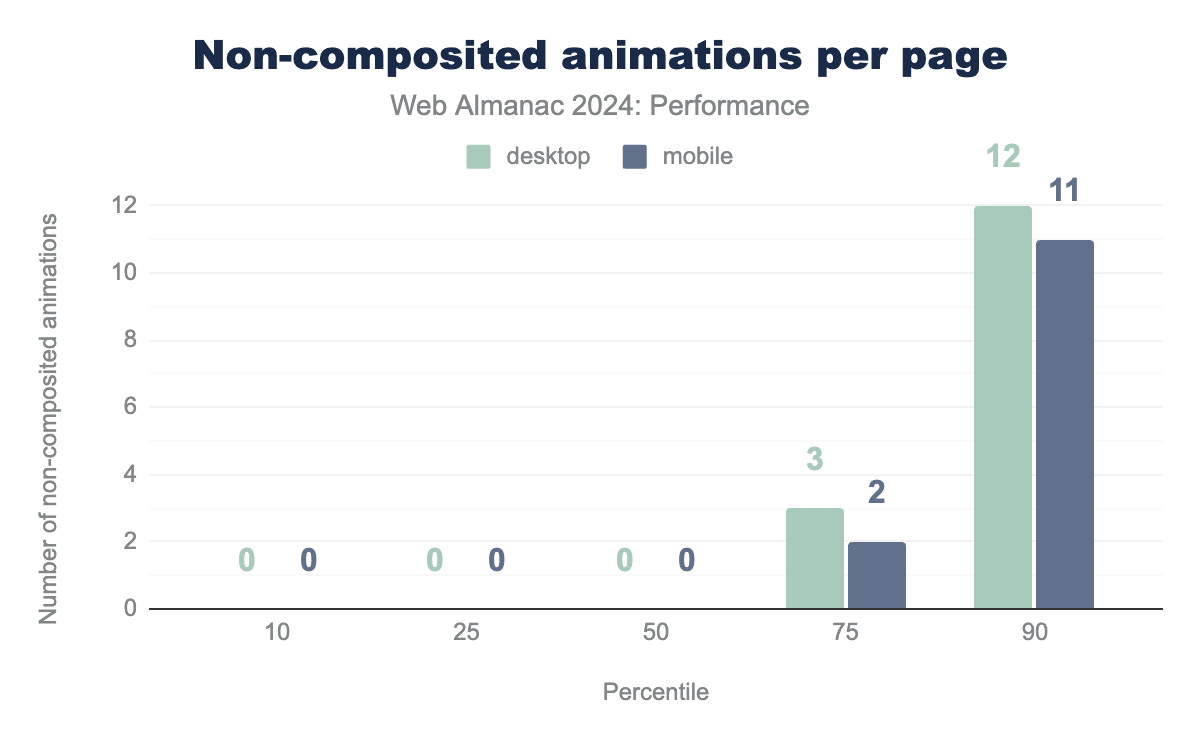

Recent data on non-composited animations provides insight into their usage across websites:

This data reveals:

- At least 50% of websites don’t use non-composited animations, which is positive from a sustainability perspective.

- There’s a significant jump in usage at the higher percentiles, with the 90th percentile showing 12 animations on desktop and 11 on mobile. This jump could severely impact the accessibility, performance, and sustainability of the webpage.

The case of carousels remains contentious: users, developers, and designers tend to despise them while organizations stick to them.

For arguments against using carousels, visit:

If animations are necessary for your design:

- Use CSS animations where possible, as they’re generally more performant than JavaScript-based animations.

- Consider using the

prefers-reduced-motionmedia query to respect user preferences for reduced motion. - Lazy-load animations that are not immediately visible on page load.

For further information, refer to:

Favicon and error pages

Favicons and error pages continue to play a subtle but important role in website performance and sustainability.

Key considerations remain:

- Always include a favicon to prevent unnecessary 404 requests.

- Ensure your favicon is properly cached to reduce repeated requests.

- Optimize your 404 page HTML to be as lightweight as possible.

- Set up redirects properly, so that users find the content they are looking for.

- While browsing to a missing page should lead to a 404 page, loading a missing resource should return a text message rather than the whole 404 HTML page (as is the case with some servers). You should also look for dead links.

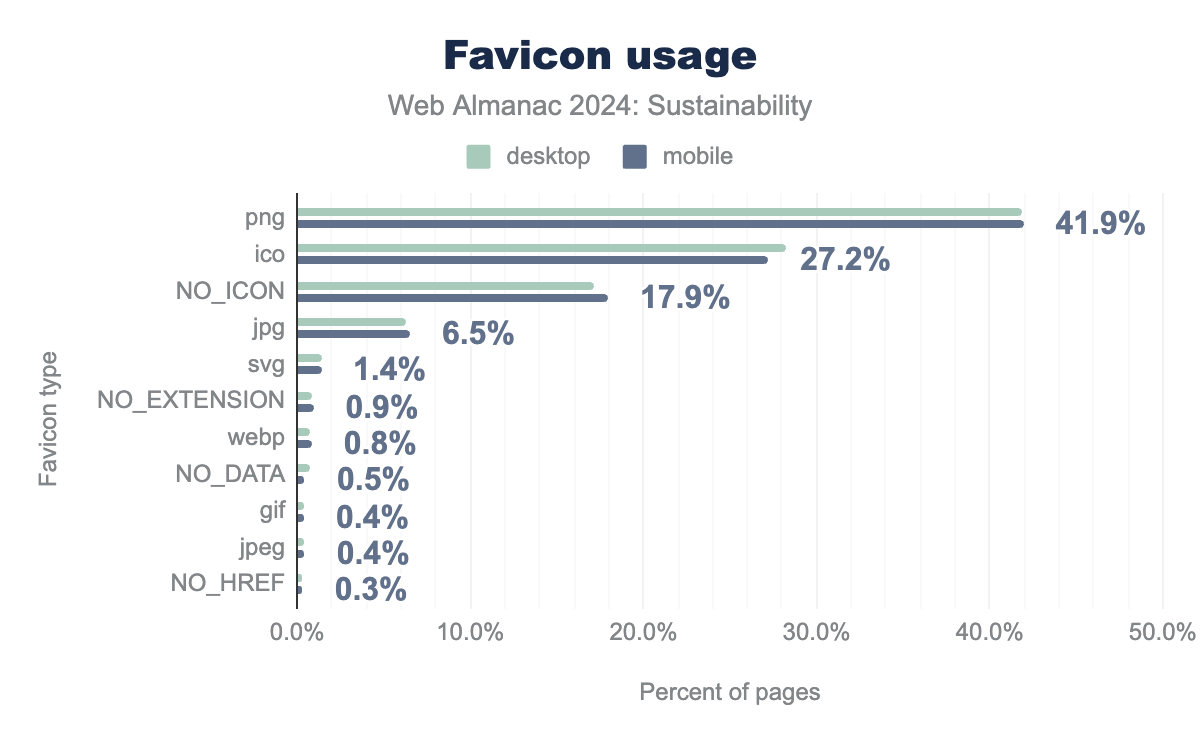

For optimal favicon sustainability:

- SVG: The ideal choice. SVGs are lightweight, scalable, and eliminate the need for multiple sizes, significantly reducing data transfer and storage needs.

- Optimized PNG: A well-optimized PNG (180x180 pixels for iOS in the base directory named apple-touch-icon.png) can be a good compromise between file size and broad compatibility. Note the filename and location requirements as browsers will seek this (based on the meta tag if used) if no SVG is provided.

- A favicon.ico with sizes 32x32 and 16x16 for compatibility purposes (older browsers will seek this within your base directory so having the file will reduce errors). These formats, when properly implemented, minimize data transfer, reduce storage requirements, and lower energy consumption across the web ecosystem. Always ensure your chosen format is properly optimized for the best sustainability impact.

When we compare the 2024 data to 2021 data (since there was no favicon data since the 2021 Markup chapter), we can say that the changes from 2021 to 2024 indicate a positive trend towards more sustainable favicon practices. The shift from ICO to more efficient formats like PNG, SVG, and WebP suggests improved awareness of file size and performance impacts. Also, the reduction in missing icons demonstrates better attention to detail, reducing unnecessary server requests. Finally, the growth in SVG and WebP usage, while still small, represents a move towards more sustainable, scalable formats.

While there’s still room for improvement, particularly in further adopting highly efficient formats like SVG and WebP, the overall trend suggests that developers are increasingly considering the sustainability implications of even small elements like favicons.

For further information, refer to:

Optimizing external content

One of the strengths of web development is the ease of integrating external content: from frameworks and libraries to third-party widgets and media. However, this convenience shouldn’t override considerations of necessity and efficiency. The environmental impact of external content is twofold: the immediate cost of transferring and processing the content, and the ongoing energy consumption from regular updates and continuous connections.

For each external element you consider adding, evaluate:

- Energy footprint: Consider both the operational energy (transfer, processing) and embodied energy (storage, infrastructure) costs

- Resource necessity: Could the functionality be achieved with a lighter, more energy-efficient solution?

- Cache efficiency: How frequently does the resource need to update, and could longer cache times reduce repeated transfers?

- Network impact: Will this resource require maintaining persistent connections or trigger frequent background requests?

Third parties

Since third-party requests make up a large portion of requests on the web, it’s interesting to make sure they come from “green” hosts. Back in 2022, we estimated that 91% of third-party requests came from “green” hosts. As of 2024, it has risen to a whopping 97%!

This sure looks like really great news but you should keep in mind this is somewhat biased. Most third-parties originate from Google whose servers are considered “green”. More generally, many cloud providers are considered “green” but the truth might be slightly more complicated, as explained in our Green Hosting section.

You should look at this year’s Third-parties chapter for more on all this.

Third-party resources, while often essential for modern web functionality, can significantly impact a website’s sustainability and performance. These external assets, ranging from scripts to stylesheets, can increase page weight and create performance bottlenecks. All of these factors contribute to higher data transfer and energy consumption.

To create more sustainable websites, it’s crucial to regularly audit and optimize third-party usage. This process might involve removing unnecessary services.

Tools like Google’s Lighthouse offer valuable insights into the impact of third-party code on site performance. The Third-Party Usage audit in Lighthouse can help identify how external resources affect page load time and overall performance.

By thoughtfully managing third-party resources, we can strike a balance between necessary functionality and website efficiency. This approach not only improves user experience but also contributes to a more sustainable web ecosystem.

Making third-party requests more sustainable

Making third-party requests more sustainable requires a strategic approach from the earliest stages of development. While outsourcing certain services can potentially reduce development time and redundancy, it’s crucial to rigorously assess each third-party component for its ecological impact.

Prioritize self-hosted content over embedded third-party services whenever possible. This approach gives you greater control over performance and emissions. For unavoidable third-party content, implement a ’click-to-load’ delay screen using the “import on interaction” pattern. This technique significantly reduces initial page load and unnecessary data transfer.

When evaluating libraries and frameworks, opt for performant alternatives that achieve the same goals with less overhead, keeping in mind that not using such tools could also be a possibility (thus sticking to vanilla JS for instance). Consider creating your own clickable icons and widgets rather than relying on third-party hosted solutions.

By carefully managing third-party integrations and prioritizing user preferences, we can significantly reduce the ecological footprint of our digital products while maintaining functionality and user experience. This is also usually beneficial to performance, security, privacy, and accessibility.

For further information, refer to:

For more detailed information on analyzing and optimizing third-party usage, refer to the Chrome Developers documentation.

Implementing technical optimizations

Historically, web performance introduced a lot of recommendations that contribute to efficiency, thus improving sustainability. It also sometimes encourages frugality. But there are still some performance recommendations that could be detrimental to environmental impacts (or at least need some discussion and careful consideration). For instance, CDN should be treated with care (see dedicated section below) and preloading or predictive loading should be avoided because they might result in loading resources that will never be used.

JavaScript

JavaScript has been an important language in the web’s growth, enabling dynamic and interactive experiences. However, when not optimized, it can also impact performance and energy consumption. Let’s focus on some quick wins: optimizations that are easy to implement and great for sustainability. These tweaks can significantly improve your site’s efficiency without sacrificing functionality. For a deeper dive into JavaScript’s pros and cons, check out our comprehensive JavaScript chapter.

Minification, tree shaking & code splitting

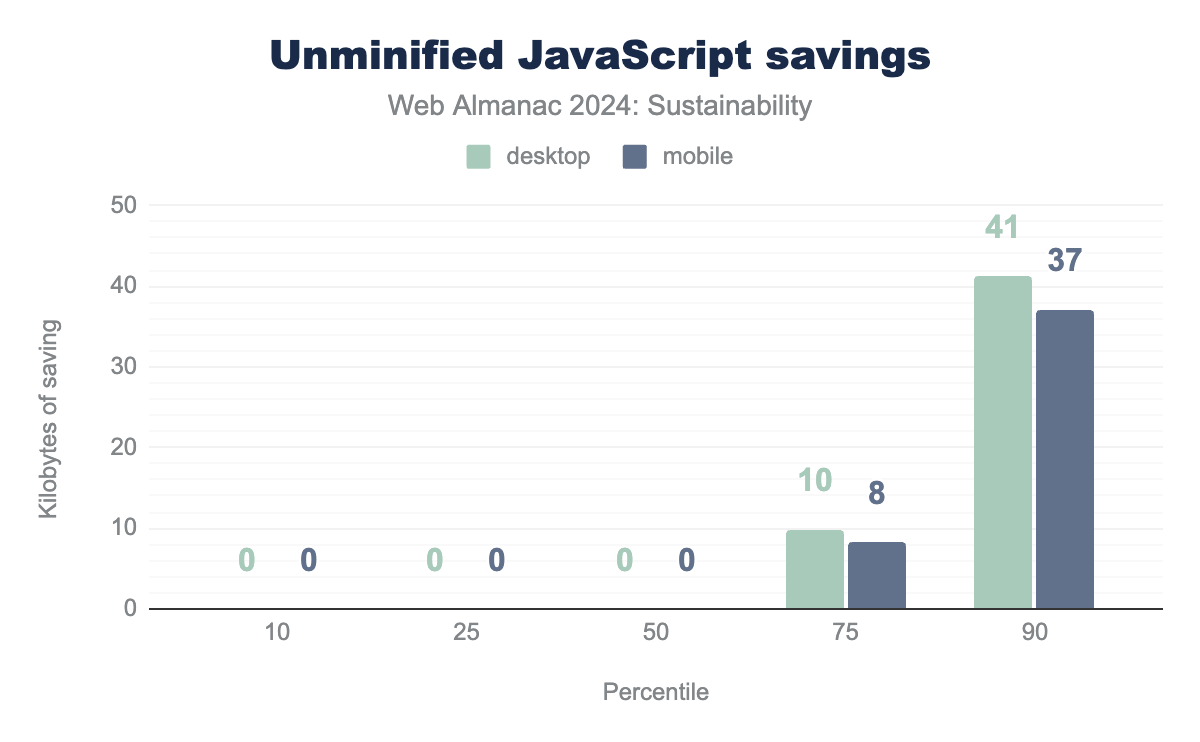

Optimizing JavaScript through minification, tree shaking, and code splitting remains crucial for improving website performance and sustainability. By focusing on these optimization techniques, we can significantly reduce data transfer, improve load times, and ultimately decrease the energy consumption associated with web browsing. Remember, even small savings per site can lead to substantial cumulative benefits across billions of page views.

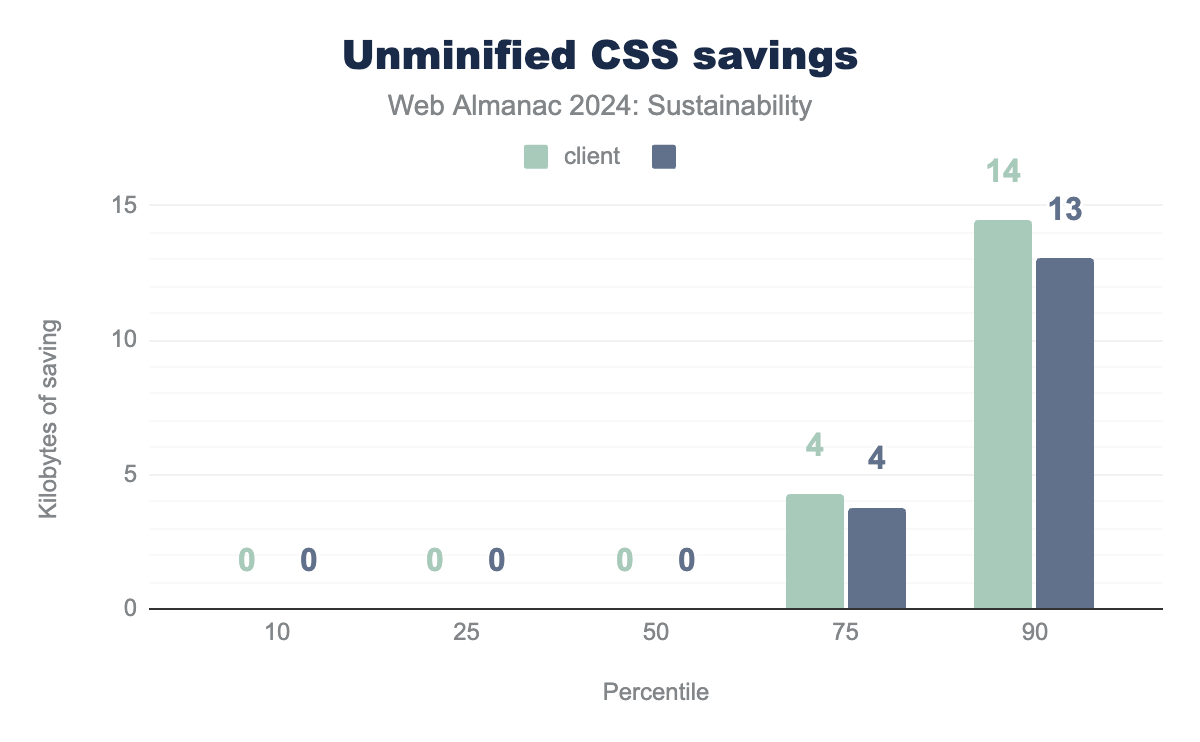

Compared to 2022, these figures show a slight increase in potential savings at the higher percentiles, indicating that some websites have accumulated more unminified code.

While many sites are effectively minifying JavaScript, there’s still significant potential for savings, especially for larger sites.

As developers, we can make our apps & websites more sustainable by:

- Implement tree shaking to eliminate dead code, which can provide additional savings beyond minification.

- Use code-splitting to load JavaScript on demand, reducing initial payload sizes.

For a deeper dive into JavaScript’s pros and cons, check out our comprehensive JavaScript chapter.

For further information, refer to:

CSS

Cascading Stylesheets (CSS) have also been a critical feature in the growth of the Internet’s popularity. The ability to add stylistic flourishes to pages and apps brings a unique visual appeal to content and features. The visual complexity of the Web however brings with it challenges in offering a sustainable product or service.

Web performance plays a critical role as too many page repaints or heavy burdens on the CPU can consume energy on the client-side. CSS also has to consider factors such as how it makes the best use of the form it is being consumed on to avoid triggering asset loading unnecessarily or wasting critical material resources if turned into a physical object (printing).

Let’s focus on some quick wins, some of which will be familiar to you from the JavaScript section to help improve your code efficiency without sacrificing functionality.

Minification

While minification for JavaScript is a common practice (as mentioned earlier in this chapter), it’s also important to recognize the value of minifying other static text assets such as CSS files due to the data savings that can be obtained. Tools within IDEs can help automate and streamline this process to increase efficiency.

Compared to 2022, these figures show a slight decrease in potential savings, suggesting a modest improvement in CSS minification practices or potentially a shift towards more efficient CSS authoring. The decrease in potential CSS savings since 2022 indicates progress, but further optimization is possible.

As developers, we can make our apps & websites more sustainable by:

- Consider using CSS Modules approaches, which can help eliminate unused styles.

- Implement critical CSS techniques to inline essential styles and defer the loading of non-critical CSS.

For further information, refer to:

Print stylesheet

Reducing the impact of physical documents is critically important because any single-use item not only uses material resources (such as paper and ink), but there is a risk involved that the item may not be recycled properly, or that its production may not come from a sustainable source. Therefore we must treat the creation of such items as a precious commodity and avoid producing more than is required to reduce excess waste.

Having a print-friendly stylesheet (using the @media print and @page at-rule) will allow you to define styles that stylistically affect how the end product will appear on the printed page. This allows you to organize content to fit onto the page better, remove content that doesn’t transcend well from digital to print (such as navigation), and include extra information where appropriate (for URLs alongside links as an example).

When creating a print-friendly stylesheet, be considerate of the user preference towards color or monochrome output, the color of paper used in the printer tray, the size of paper provided for printing, and the orientation of paper (responsive design of a sort that exists in print).

For further information, refer to:

User preferences (dark mode)

Visitors have their preferred way of browsing websites, and one of the most common preferences is “lights on or off” otherwise known as the use of dark mode. While this may outwardly appear to be a visual or stylistic choice, there are some sustainability and accessibility considerations to take into account with this choice.

Before we get into the sustainability benefits, it is worth quickly discussing that while the use of dark mode for some people can increase readability, it can affect others negatively by acting as a trigger for people with astigmatism, It is therefore important that the ability to turn on and off features like dark mode be available to visitors and user preferences (on OS or browser) taken into account.

Dark mode itself can be a real benefit for sustainability on OLED screens due to the use of dimmed pixels (blacks and low colors). Studies have shown that on such devices the reduction of energy use can vary but it does make a real difference (and as the screen is the primary energy emitter for handheld devices, this is important).

There are several other user-preference media queries available to CSS that may (depending on usage) have sustainability benefits for your visitors such as monochrome (to default printing to a single cartridge type), prefers-reduced-motion (to reduce processor-intensive animated effects), and the upcoming prefers-reduced-data (that allows designing around low bandwidth devices).

For further information, refer to:

Including as little code as possible directly in HTML

The practice of inlining JavaScript and CSS directly in HTML can bloat HTML files and potentially harm overall performance and sustainability, as well as security. This issue is particularly prevalent in websites built with Content Management Systems (CMS) and those implementing the Critical CSS method.

The importance of the separation of concerns (HTML, CSS, and JavaScript) cannot be understated as also touched upon earlier in this chapter. While CSS can’t defer or asynchronously load assets like JavaScript that would be render-blocking (without reliance on JavaScript itself), it still retains the same key benefit of being able to cache such assets. In doing so, a large library of CSS styles can be re-used among many pages without having to be re-downloaded.

For further information, refer to:

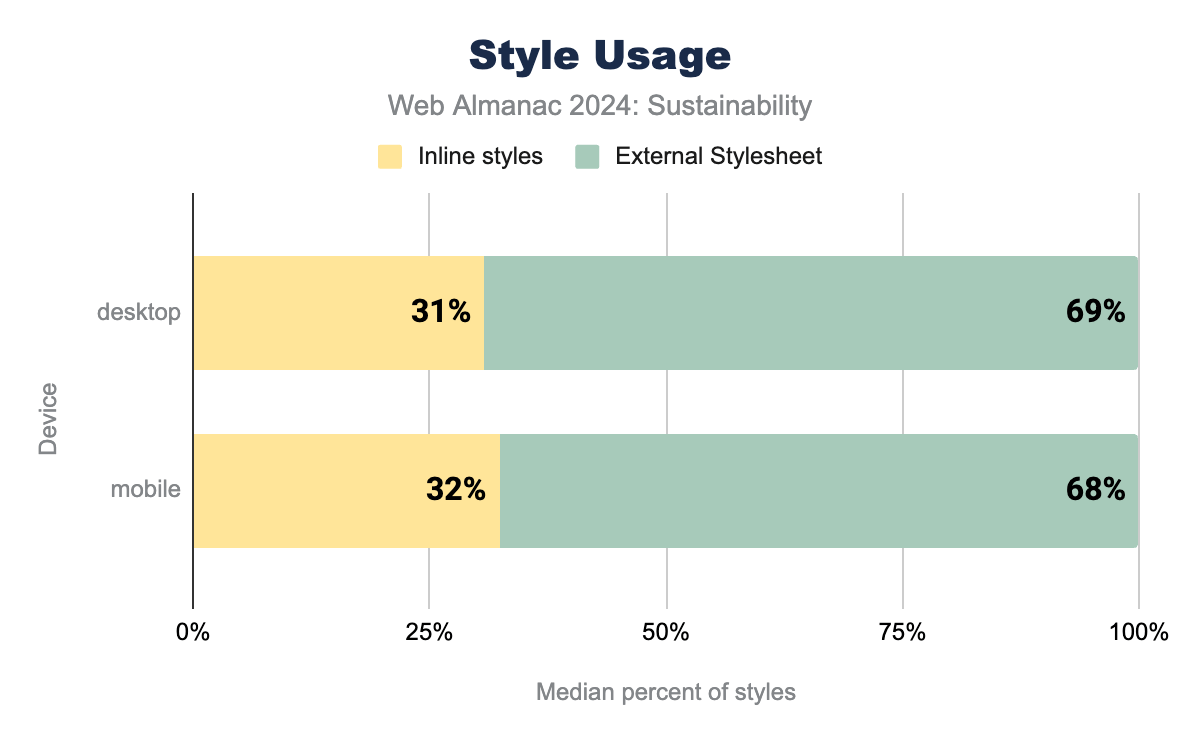

When we compare this year’s data to 2022 data we can see the following:

-

Increase in inline stylesheet usage:

- Desktop: from 25% in 2022 to 31% in 2024.

- Mobile: from 25% in 2022 to 32% in 2024.

-

A corresponding decrease in external stylesheet usage:

- Desktop: from 75% in 2022 to 69% in 2024.

- Mobile: from 75% in 2022 to 68% in 2024.

This trend shows a clear shift towards more inlining of CSS, particularly on mobile devices. While this approach can improve initial render times by reducing HTTP requests, it also presents challenges:

- Increased HTML file sizes, potentially slowing down initial page loads.

- Reduced caching efficiency, as inline styles, can’t be cached separately from HTML.

- Potential for redundant code across multiple pages. In the end, even though inlining critical CSS could help reduce the initial render time we must be careful to not inline more than that because it could have the exact opposite effect and delay the initial render.

Obsolete code

In the rapidly evolving landscape of web development, obsolete code is an often overlooked source of inefficiency that can significantly impact a website’s sustainability footprint.

Obsolete code refers to unnecessary, outdated, or redundant code that remains in a codebase. This can include:

- Deprecated JavaScript and CSS features.

- Polyfills for outdated browsers.

- Unused functions or styles from previous iterations of a site.

- Legacy code supporting discontinued features.

From a sustainability perspective, obsolete code is problematic for several reasons:

- Increased File Size: Obsolete code bloats JavaScript and CSS files, leading to larger file sizes. This results in increased data transfer, consuming more energy both in transmission and processing.

- Unnecessary Processing: Browsers still need to parse and execute obsolete code, even if it’s not used. This consumes additional CPU cycles and, consequently, more energy on user devices.

- Maintenance Overhead: Obsolete code makes codebases harder to maintain, potentially leading to inefficient workarounds and further code bloat over time.

- Security: Obsolete code is much more likely to have known security issues that could put users at risk.

For further information, refer to:

CDN

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) play a crucial role in optimizing web performance and, by extension, improving the sustainability of web applications. By distributing content across multiple, geographically dispersed servers, CDNs reduce the distance data needs to travel, leading to faster load times and reduced energy consumption.

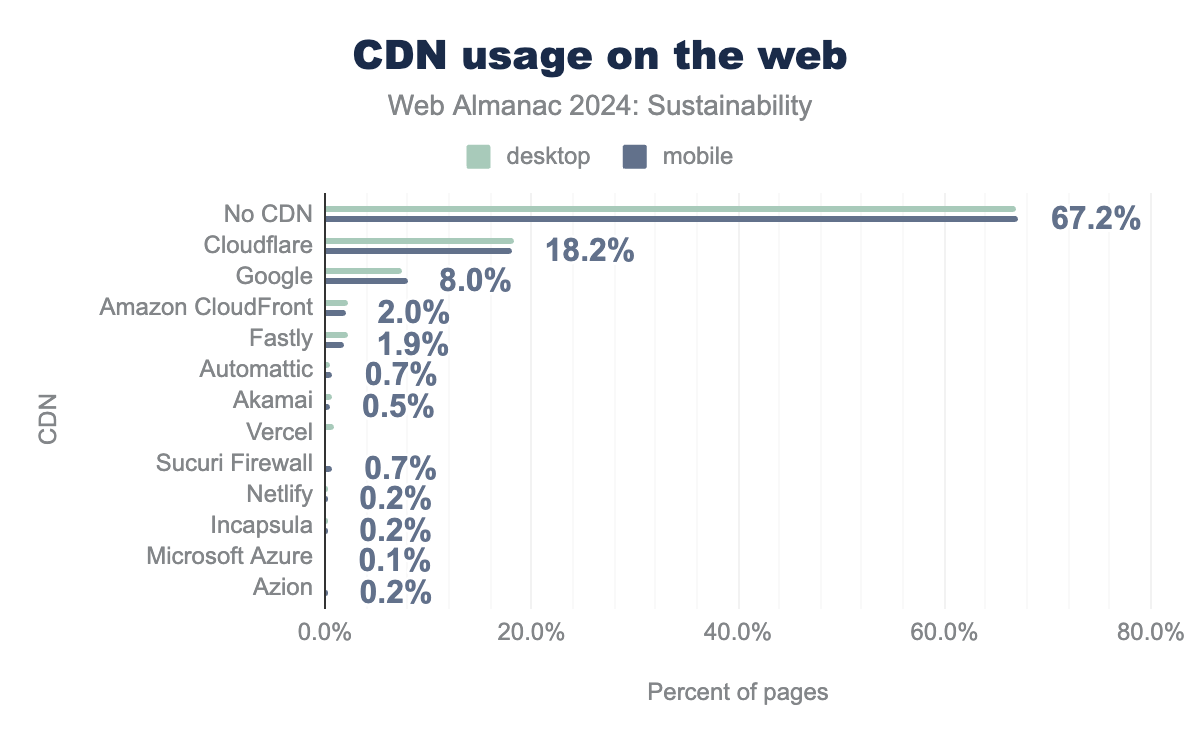

Comparing this data to 2022 data, we observe several notable trends:

- Increased CDN Adoption: The percentage of websites not using a CDN has decreased from 69.7% to 66.88% for desktop and from 71.2% to 67.20% for mobile. This indicates a growing recognition of CDN benefits.

- Cloudflare’s Growth: Cloudflare has solidified its position as the leading CDN provider, increasing its market share from 16.9% to 18.28% on desktop and from 15.1% to 18.16% on mobile.

- Google’s Expansion: Google’s CDN usage has seen significant growth, rising from 5.2% to 7.40% on desktop and from 6.5% to 7.95% on mobile.

- Shifts in the Market: While Fastly has seen a slight decrease in usage, Amazon CloudFront has maintained its position. Newer players like Vercel have entered the top 10, indicating a dynamic and evolving CDN market.

From a sustainability perspective, the increased adoption of CDNs is a positive trend:

- Reduced Data Travel: By serving content from geographically closer locations, CDNs minimize the distance data needs to travel, reducing overall network energy consumption.

- Improved Caching: CDNs often provide advanced caching mechanisms, reducing the need for repeated data transfers and server processing.

- Load Balancing: By distributing traffic across multiple servers, CDNs can help prevent server overload, potentially reducing energy consumption during traffic spikes.

- Edge Computing: Many modern CDNs offer edge computing capabilities, allowing for data processing closer to the end-user, which can further reduce energy consumption.

For a deeper dive into CDNs, check out our comprehensive CDN chapter.

For further information, refer to:

Text compression

Text compression is a crucial technique for reducing the size of transmitted data, playing a significant role in improving both website performance and sustainability. By compressing text-based resources such as HTML, CSS, and JavaScript before sending them over the network, we can substantially reduce data transfer and, consequently, energy consumption.

Common text compression methods include:

- Gzip: Widely supported and effective for most text-based content, typically achieving 60-80% compression ratios.

- Brotli: A newer algorithm that often outperforms Gzip, especially for smaller files, with potential compression improvements of 15-25% over Gzip.

- Zopfli: A Gzip-compatible algorithm that can achieve better compression ratios but at the cost of longer compression times, making it suitable for static content.

- Zstandard (zstd) is also a serious contender that shows great performance for both compression and decoding.

More on this in this article from Paul Calvano.

The data shows that over half of websites are not using any form of text compression, with 53.47% of desktop sites and 51.38% of mobile sites sending uncompressed content. This represents a significant missed opportunity for reducing data transfer and, consequently, energy consumption.

Among sites using compression, Gzip is slightly more prevalent than Brotli, being used by 24.05% of desktop sites and 24.65% of mobile sites. Brotli, despite its superior compression capabilities, is used by 21.59% of desktop sites and 23.03% of mobile sites.

Given that text compression can significantly reduce data transfer volumes, the widespread lack of adoption represents a substantial opportunity for enhancing the web’s energy efficiency. Encouraging the use of compression, particularly more efficient algorithms like Brotli, could lead to meaningful reductions in data center energy usage, network traffic, and client-side processing requirements.

As we move towards a more sustainable web, text compression remains a key tool in our optimization toolkit, offering a relatively simple yet highly effective way to reduce our digital carbon footprint.

For further information, refer to:

Caching

Caching is a crucial technique in web optimization that significantly contributes to sustainability efforts. By reducing the need for repeated data transfers and server processing, caching plays a vital role in minimizing the energy consumption associated with web operations.

From a sustainability perspective, effective caching offers several key benefits:

- Reduced Data Transfer: By storing resources closer to the user, caching dramatically decreases the amount of data transmitted over networks. This directly translates to lower energy consumption across the web infrastructure.

- Decreased Server Load: With fewer requests reaching origin servers, the overall energy usage in data centers can be significantly reduced.

- Cumulative Environmental Impact: For frequently accessed resources, the energy savings compound with each cache hit, potentially leading to substantial reductions in overall carbon footprint over time.

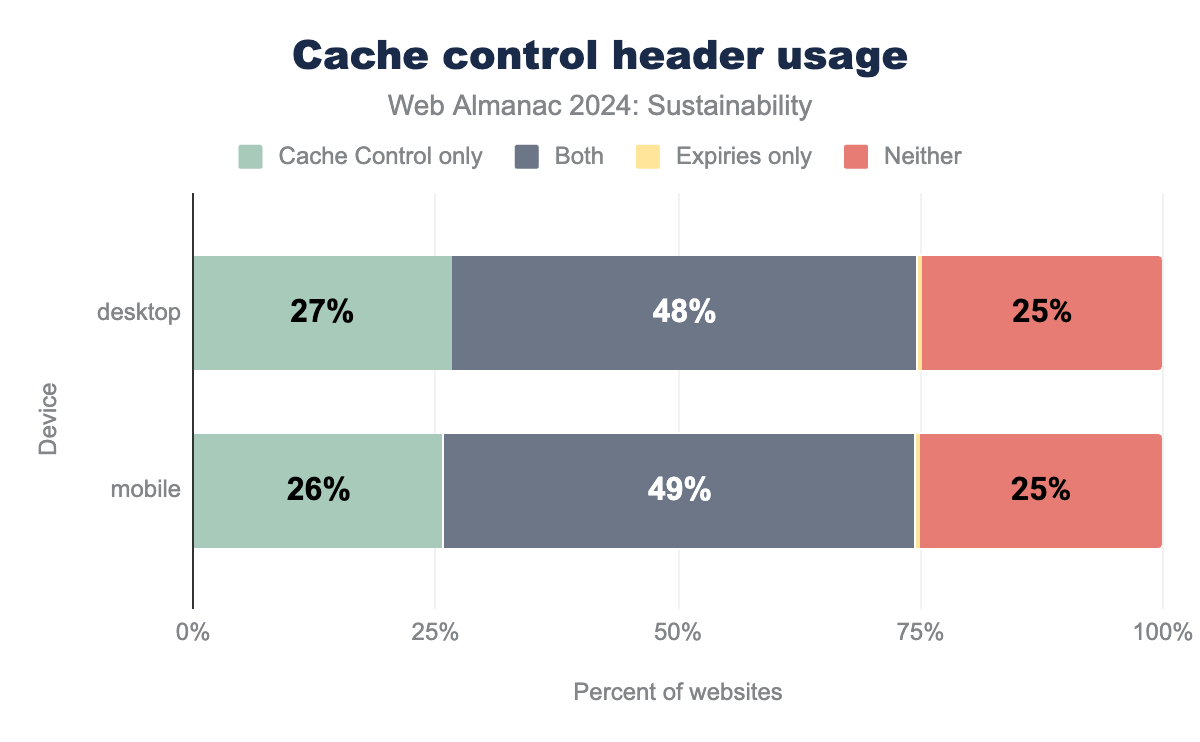

An analysis of cache header usage between 2022 and 2024 reveals subtle shifts in caching practices:

- The use of both Cache-Control and Expires headers has slightly decreased, from 51% to 48.08% on desktop and 48.57% on mobile. Conversely, the use of Cache-Control only has increased from 23% to 26.65% on desktop and from 22% to 25.92% on mobile.

- The percentage of sites using neither caching header has remained relatively stable, with a marginal decrease from 25% to 24.89% on desktop and a slight decrease from 26% to 25.13% on mobile.