HTTP

Introduction

HTTP remains the cornerstone of the web ecosystem, providing the foundation for exchanging data and enabling various types of internet services. It is an actively developed protocol, with the latest version HTTP/3 standardized a little over two years ago, and new options to enable it recently becoming available, such as the new DNS HTTPS records. At the same time, the web platform has been exposing more and more higher-level features that web developers can use to influence when and how resources are requested and downloaded over HTTP. This includes options like Resource Hints (for example preload and preconnect), 103 Early Hints and the Fetch Priority API.

In this chapter, we will first look at the current state of HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 adoption, and how their usage has evolved over time. We then consider the new web platform features, to get an idea of how well they’re supported and how people are using them in practice.

HTTP version adoption

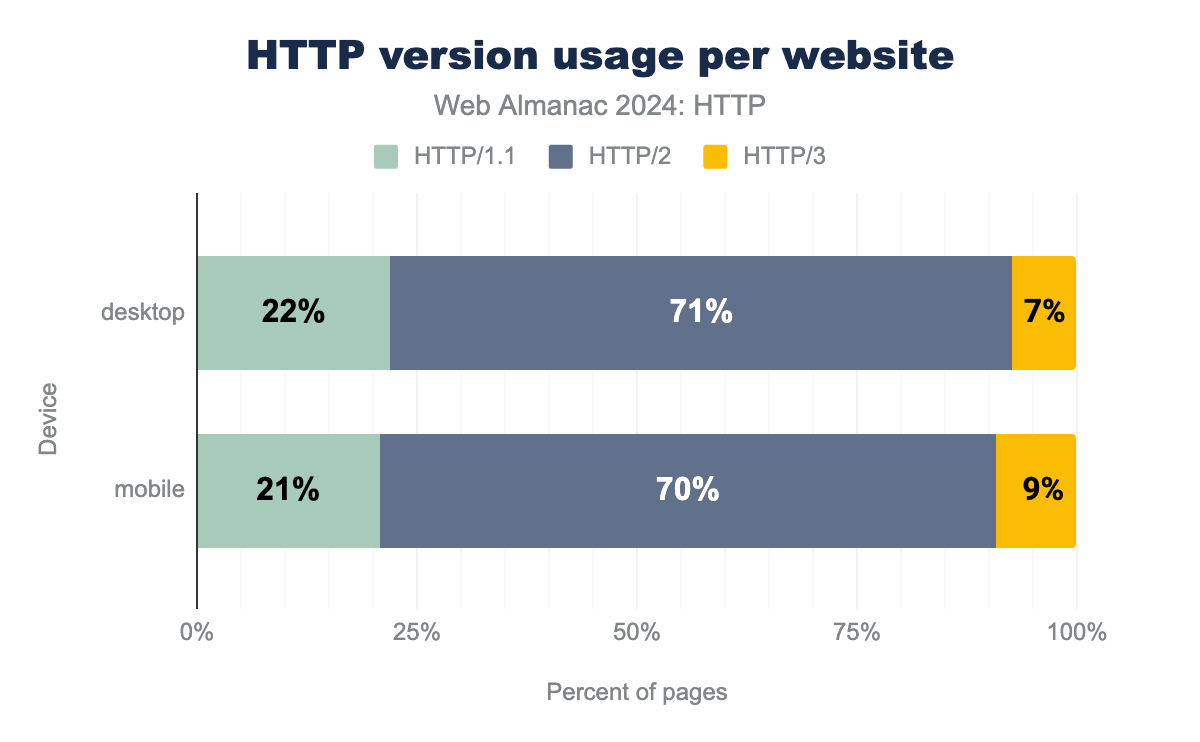

Conceptually, getting an idea of how widespread the adoption of HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 is should be easy: just report how often each of the protocol versions was used to load the observed web pages in our dataset. This is exactly what we’ve done in the graph below:

While these results might look sensible at first glance, they are actually quite misleading. Indeed, as we’ll see later, in reality HTTP/3 support across the web is closer to 30% instead of the 7-9% reported above. This discrepancy is due to the fact that HTTP/3 has to be discovered before being used, while the methodology used for the Web Almanac doesn’t really lend itself well to the main discovery option (see HTTP/3 via alt-svc). This causes a lot of HTTP/3-capable sites to still be loaded over HTTP/2 and thus HTTP/3 is getting underreported. We will discuss this in more detail below, but for now we will bypass this issue by grouping HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 together into a single label of HTTP/2+ to at least compare them to HTTP/1.1 in general.

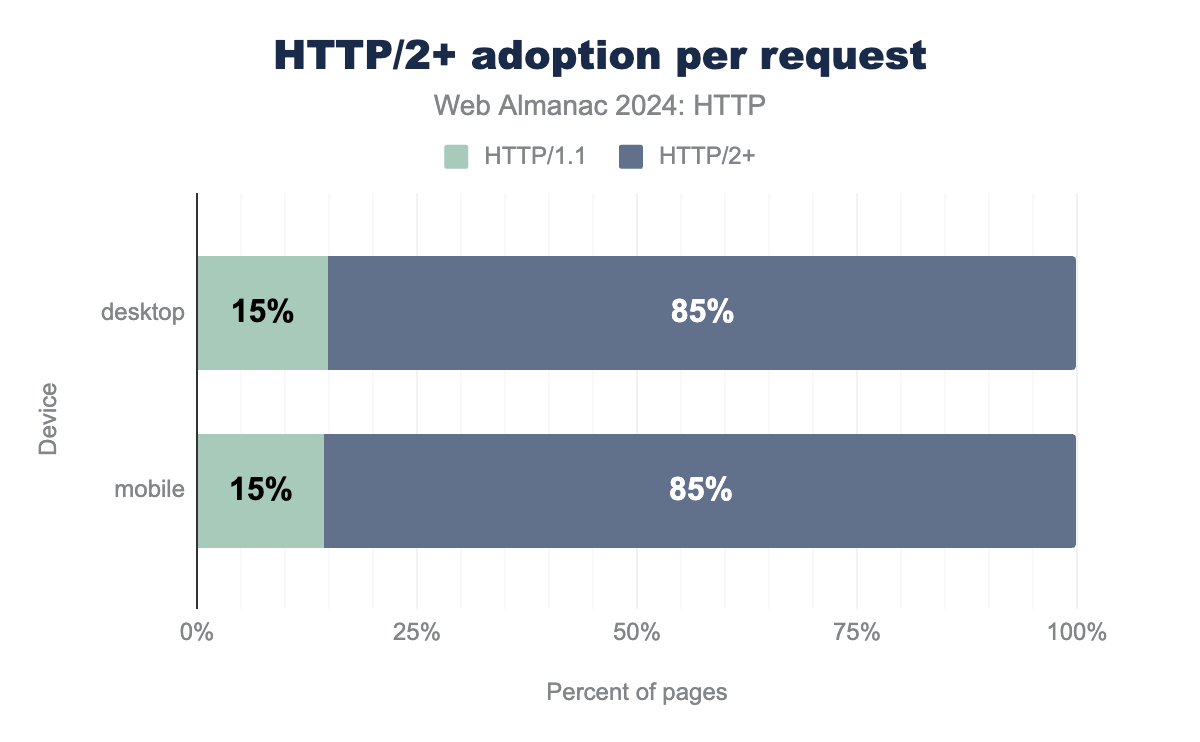

As such, we see that only 21-22% of home pages are loaded over HTTP/1.1 in 2024, a marked difference from 2022 where it was still 34% and especially 2020 where there was basically a 50/50 split between HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2+. However, this is just looking at how the main document (the HTML) of the page is loaded. Another way of looking at HTTP adoption is by looking at the version used for all requests (including subresources and third-parties), which skews the results even more towards HTTP/2+:

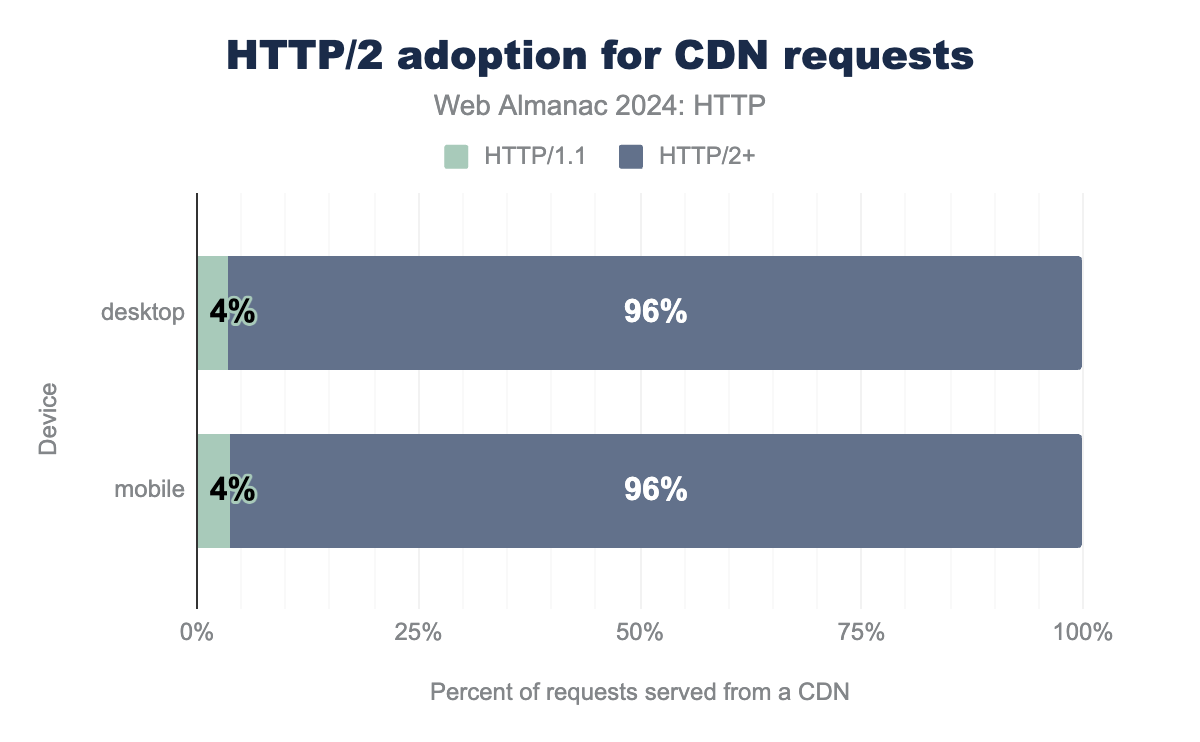

This is because many websites will load additional resources from a variety of third-party domains (for example, analytics, plugins/tags, and social media integrations). Due to their scale, these external services often either provide support for HTTP/2+ themselves or make use of a so-called CDN or Content Delivery Network (for example Akamai, Cloudflare or Fastly) that does it for them. In fact, CDNs are used very heavily on the observed websites in our dataset, with a whopping 54% of over 1.3 billion requests in our dataset being served from a CDN!

These companies are typically at the forefront of implementing new standards and protocols. When they enable a new feature, it becomes available to all their customers, usually causing a fast increase in global adoption. As such, we can see that CDNs are still one of the main drivers of HTTP/2+ adoption, with less than 4% of all CDN requests happening over HTTP/1.1. This is again in stark contrast to requests not served from a CDN node, of which up to 29% still use HTTP/1.1.

Combined, these results show that while overall adoption of newer HTTP versions is higher than ever, there are still plenty of sites that are in danger of “being left behind”. These are mostly the (likely smaller) projects that can’t or won’t engage a CDN, but also don’t have the technical know-how or motivation to enable HTTP/2+ themselves at their origins. Conceptually, this makes sense, as the newer versions do have some costs associated with them, both in terms of complexity and—especially for HTTP/3—in terms of CPU usage. And while HTTP/1.1 of course still functions perfectly fine, there might be some performance/efficiency downsides, as only HTTP/2+ allows multiplexing of multiple resources onto one connection, as well as additional features like resource prioritization and header compression.

Still, personally I feel it’s good to have freedom of choice on the web, not just in terms of content, but also the tech stacks that are used, and that includes the protocols. Importantly, the current (over)reliance on CDNs (for performance and security) also does have its own downsides, with some people fearing a “centralization” of the web around a few large companies. I don’t think we’re quite there yet, but I have written previously about the worrying fact that it is increasingly only the CDNs/large companies that have the technical know-how to deploy the newer protocols at scale. I don’t know the right answer here, but feel it’s good to highlight both sides! However you feel about this, it is clear that CDNs already make up a large part of the web today, and that they are driving adoption of the newer HTTP versions.

Let’s thus move away from the philosophical back into the (deeply) technical now, and explore why exactly the Web Almanac dataset is only seeing low percentages of HTTP/3 being used!

Discovering HTTP/3 support

Measuring HTTP/3 adoption can be challenging because most modern browsers and clients will not try HTTP/3 the first time they load a page from a domain they haven’t seen before. The reasons why are complex and were explained in detail in previous Web Almanacs (2020 and 2021). The short version is that it could take the browser a (very) long time to fall back to HTTP/2 (or HTTP/1.1) if HTTP/3 is not available for the target domain—for example if the server doesn’t support it yet, or if the network is blocking the protocol.

This is less of a problem for HTTP/2 and HTTP/1.1, as they both run over the TCP protocol. If the server doesn’t support HTTP/2, it can just continue with HTTP/1.1 over the existing TCP connection the browser set up, getting an “instant fallback”. HTTP/3 however is different, as it replaces TCP with a new transport protocol called QUIC which in turn runs over the UDP protocol. If the browser only opens a QUIC+HTTP/3 connection to a server that doesn’t support it, that server wouldn’t be able to fall back to HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1, since that’s only possible over TCP, not QUIC/UDP. It would have to wait for the HTTP/3 connection to timeout (which can take several seconds) and only then open a new TCP connection for HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1, which would be very noticeable for the end users.

To prevent users suffering this potential delay, the browser will in practice only try HTTP/3 if it’s 100% sure the server will support it. But how can it be 100% sure? Well, if the server/deployment explicitly tells the browser it supports HTTP/3 first, of course!

There are two main ways of doing this:

-

The

alt-svcHTTP response header: the HTTP server advertises HTTP/3 support when a resource is requested over HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1 - The DNS HTTPS resource record: the DNS server indicates HTTP/3 support during name resolution, before connection establishment

The first option is by far the most popular today, but has the downside that it first needs a “bootstrapping” connection over HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1 to discover HTTP/3 support. The second option removes this downside by putting the information directly in the Domain Name System (DNS), which resolves before the first HTTP connection is even made. It is however much newer and thus less supported at the moment of writing.

To get a good idea of real HTTP/3 support in the Web Almanac dataset, we need to consider both separately, as they will give conflicting results.

HTTP/3 via alt-svc

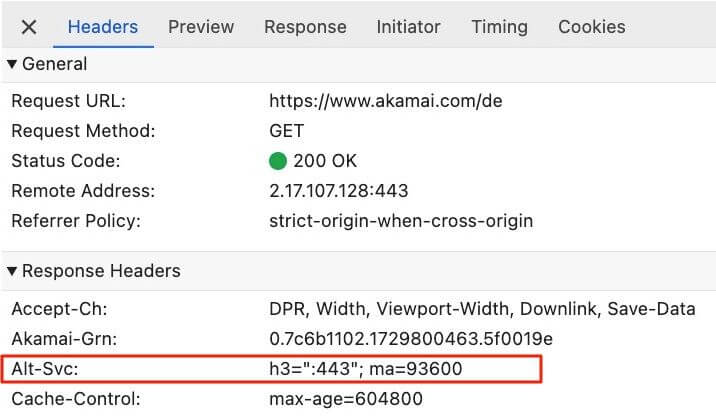

As discussed above, if the browser hasn’t connected to a domain before, it will only try HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1 over TCP, as those are most likely to be supported. For each HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1 response, the server can then send along a special alt-svc HTTP response header, indicating it is guaranteed to support HTTP/3 as well—at least for a specified timeframe: the ma (max-age) parameter.

alt-svc HTTP response header supporting HTTP/3 on UDP port 443 with ALPN value h3 and max-age of 26 hours for www.akamai.comalt-svc response header example.

alt-svc stands for Alternative Services: you’re currently using the HTTP/2 service, and there’s also an HTTP/3 service available (usually at UDP port 443). From then on, when the browser needs a new connection to the server, it can try to establish it over HTTP/3 as well! Using this mechanism thus means that HTTP/3 is typically only used from the second page load of a site onward, as the first load will happen over H2 or HTTP/1.1, even if the server supports HTTP/3. And that is the crux of the issue here, as the Web Almanac only measures the first page load by design.

In order to make results comparable and fair across websites, we want to load each page with a fresh browser profile and nothing in the HTTP/file/DNS/alt-svc/… caches. As such, the alt-svc mechanism is conceptually useless in our methodology, as we’d only use the initial HTTP/2 connection and never get to HTTP/3. This is why measuring HTTP/3 adoption directly by protocol used in our dataset (as we did in the first image above) is misleading, with HTTP/3 getting underreported.

Let’s now look purely at how HTTP/3 support is being announced via alt-svc to get an idea of how much support sites claim to have, even if it doesn’t actually show up in our dataset:

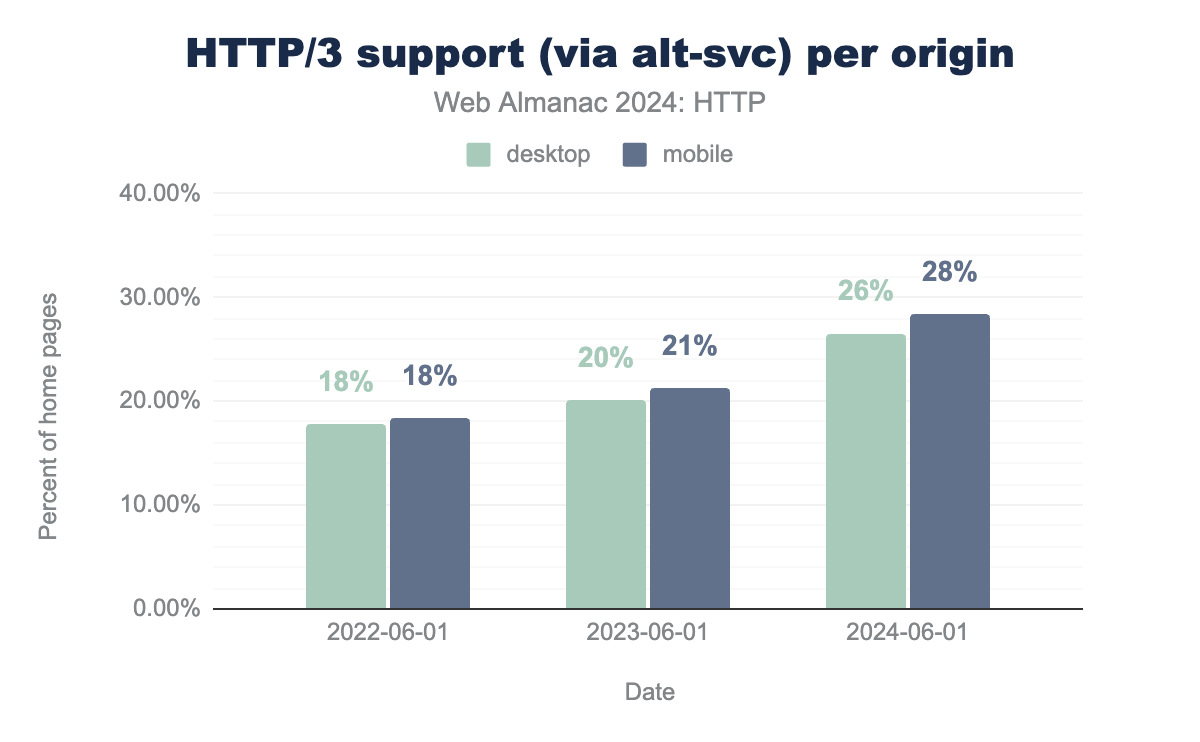

alt-svc) has increased steadily since 2022.

When we last looked at HTTP/3 support in June 2022, the protocol wasn’t even fully standardized yet. Still, due to early deployments from some large players, around 18% of sites in the HTTP Archive dataset indicated they had support for HTTP/3. Now, two years later, we can see that support for the new protocol has steadily risen, up to 26% (desktop) to 28% (mobile), a near 10% overall increase. If that still seems low, it’s actually quite similar to HTTP/2’s evolution, which equally saw around 30% uptake in its second year after standardization (2017).

It is somewhat interesting to see that mobile home pages advertise a little better support for HTTP/3 than their desktop counterparts. This can potentially be explained by the fact that HTTP/3 will mainly deliver benefits over mobile/cellular networks (and so site owners might want to mainly enable it for that) and because some corporate environments still tend to block HTTP/3 on their networks (making it less interesting to enable for desktop clients).

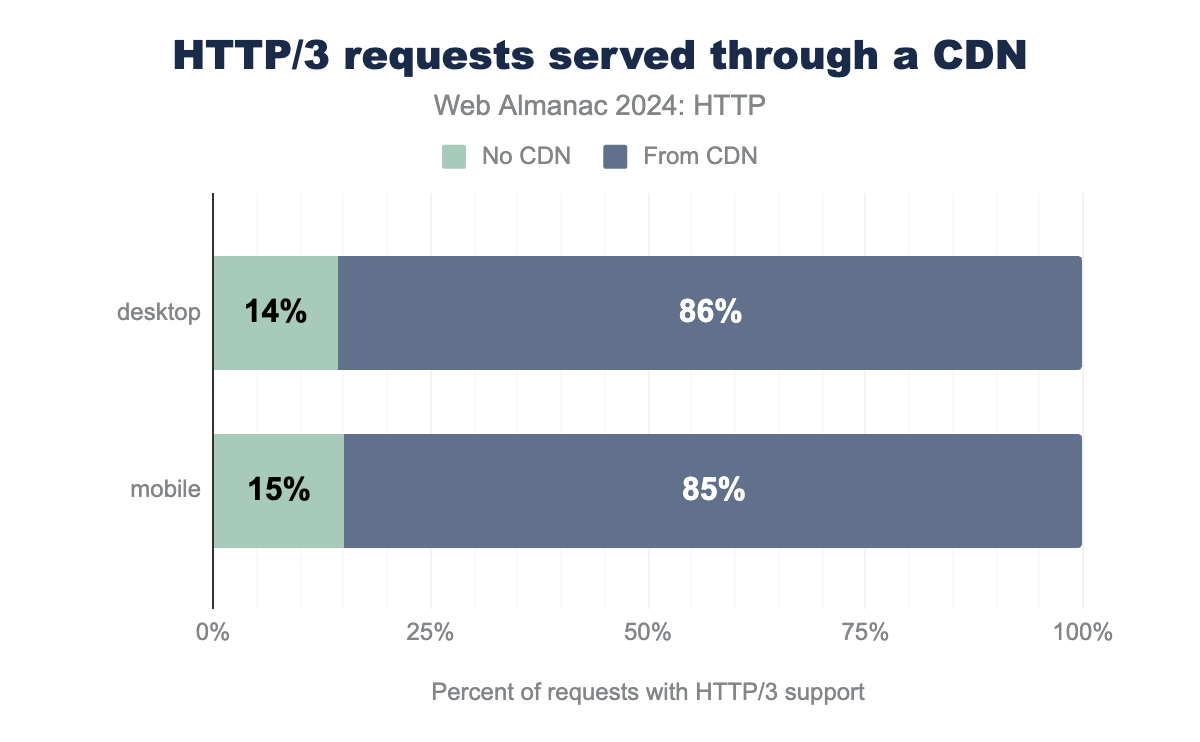

Similar to HTTP/2+ above, the support for HTTP/3 comes mainly from the CDNs, but in a quite extreme form in my opinion: around 85% of all HTTP/3 responses seen in our dataset came from a CDN. This compares to around 55% of all HTTP/2+ requests. This indicates that today very few website owners are self-deploying HTTP/3 at their origin and re-emphasizes my point from above that fast adoption of new technologies might (sadly) become a large-company-only thing. This is not entirely unexpected however; a lot of the popular “off the shelf” web servers do not have stable, mature, on-by-default HTTP/3 support yet-including projects like NodeJS, Apache and nginx. Running a scalable HTTP/3 deployment that uses some of the protocol’s more advanced features, like connection migration and 0-RTT, is far from easy. Still, I hope to see more people self-hosting HTTP/3 in the near future.

One important remark to make here is that not all CDNs show equally high HTTP/3 support:

HTTP/3 alt-svc |

CDN |

|---|---|

| > 90% | Facebook, Automattic, jsDelivr |

| 50% - 90% | Cloudflare, Cedexis |

| 10% - 50% | Google, Amazon Cloudfront, Fastly, Microsoft Azure, BunnyCDN, Alibaba, CDN 77 |

| 1% - 10% | Akamai, Sucuri Firewall, Azion, KeyCDN |

| < 1% | Twitter, Vercel, Netlify, OVH CDN, EdgeCast, G-Core CDN, Incapsula |

alt-svc responses for all requests served by first-party CDNs (with considerable traffic share).

Firstly, we see that some companies seem to go all-in on HTTP/3, with Facebook for example indicating HTTP/3 support on 99.86% of responses! This is in stark contrast to similar companies like Twitter/X, that don’t send alt-svc at all. Secondly, even some CDNs that clearly support HTTP/3 rarely reach high percentages, with Cloudflare leading the pack at 78% and Akamai tagging along at just 7%.

This most likely has to do with how exactly the CDNs enable the new protocol. For example, Cloudflare has enabled it by default for their free plans, leading to high (though not universal) use. In contrast, Akamai requires its customers to manually enable the feature in their configuration, which many seem slow/unwilling to do. As such, the amount of HTTP/3 support on the web could be much higher than around 28% if all CDN customers would enable it.

Finally, it is somewhat surprising that some more specialized deployments, like Automattic, heavily lean into HTTP/3 (99.92%) while others like Vercel and Netlify show near-zero HTTP/3 support. I can only speculate on the reasons for the latter, but assume it is mostly due to the complexity of setting up and maintaining the new protocol at scale, while these newer up-and-coming companies might prefer to focus on other parts of their stacks first.

In conclusion, we see that currently around 27% of all websites in the Web Almanac dataset announce HTTP/3 support through alt-svc. This number could potentially be much higher, if all websites that use a compatible CDN would enable it. At the same time however, the actual number of HTTP/3 requests we’ve seen in the dataset is much lower, between 7-9%. As we’ve explained, this is due to the used methodology and most of those 7-9% will come from another HTTP/3 discovery method using DNS records, so let’s look at those next.

HTTP/3 via DNS

We now understand that announcing HTTP/3 support via an alt-svc HTTP response header has some downsides, leading to the newer protocol only being used from the second connection to a server onwards. To get rid of this inefficiency, the browser would have to discover HTTP/3 support before it even opened the first connection to the server. Luckily, there is still one thing that happens before a connection can be setup and that is: DNS resolution.

The Domain Name System (DNS) is often described as a large phone book, which allows you to translate a hostname (for example www.example.org) into one or more IP addresses (with A and AAAA queries returning IPv4 and IPv6 results respectively). However, in essence, the DNS can also be thought of as just a very large, distributed Key-Value store that can hold other things besides IP addresses (and associated metadata like CNAMEs) as well. Some examples include listing email details with MX records, and using TXT records to prove ownership of a domain (for example for Let’s Encrypt).

The past few years, work has been ongoing to also add other information to the DNS, in particular with the new concept of Service Binding (SVCB) and HTTPS records. These new records provide the client with a lot more information about a service/origin than just its IP addresses: whether it’s HTTPS capable, whether it can use the new Encrypted Client Hello for extra privacy, or for our purposes, which protocols it supports and on which ports. This is intended to make initial connection setup/service discovery a bit more efficient, as currently this is often done through slower methods like a chain of redirects or the above alt-svc, or requires out-of-band methods like HSTS preload. They are also intended to help with complex load balancing setups (for example when combining multiple CDNs).

A full discussion on SVCB would take too much time here however, so we will focus only on how we can announce HTTP/3 support through the new HTTPS record as there are plenty of other blog posts and documents with more details on the wider applications. Let’s look at an example of the HTTPS record in the wild:

dig command line tool showing a DNS HTTPS record listing alpns h3 and h2, and providing both an ipv4hint and ipv6hint for blog.cloudflare.comAs we can see, blog.cloudflare.com indicates support for both HTTP/3 and HTTP/2 (in order of preference!) via the alpn="h3,h2" part of the response. ALPN stands for Application Layer Protocol Negotiation which was originally a TLS (Transport Layer Security protocol) extension to indicate which application protocols and versions a server supports. For example, to allow the graceful fallback from HTTP/2 to HTTP/1.1 discussed above.

The general approach—and ALPN name—is reused for the DNS HTTPS record as well. Additionally, the example shows the optional ipv4hint and ipv6hint entries, which allow steering of users to specific endpoints for specific services. For example, if not every single machine in the deployment actually supports HTTP/3 yet, say in a multi-CDN setup.

In conclusion, if a browser queries the DNS for the HTTPS records (which is typically done in parallel or even before A and AAAA queries), and subsequently sees h3 in the ALPN list, then it is allowed/encouraged to also try HTTP/3 for its first connection to the server. This bypasses the alt-svc bootstrapping overhead.

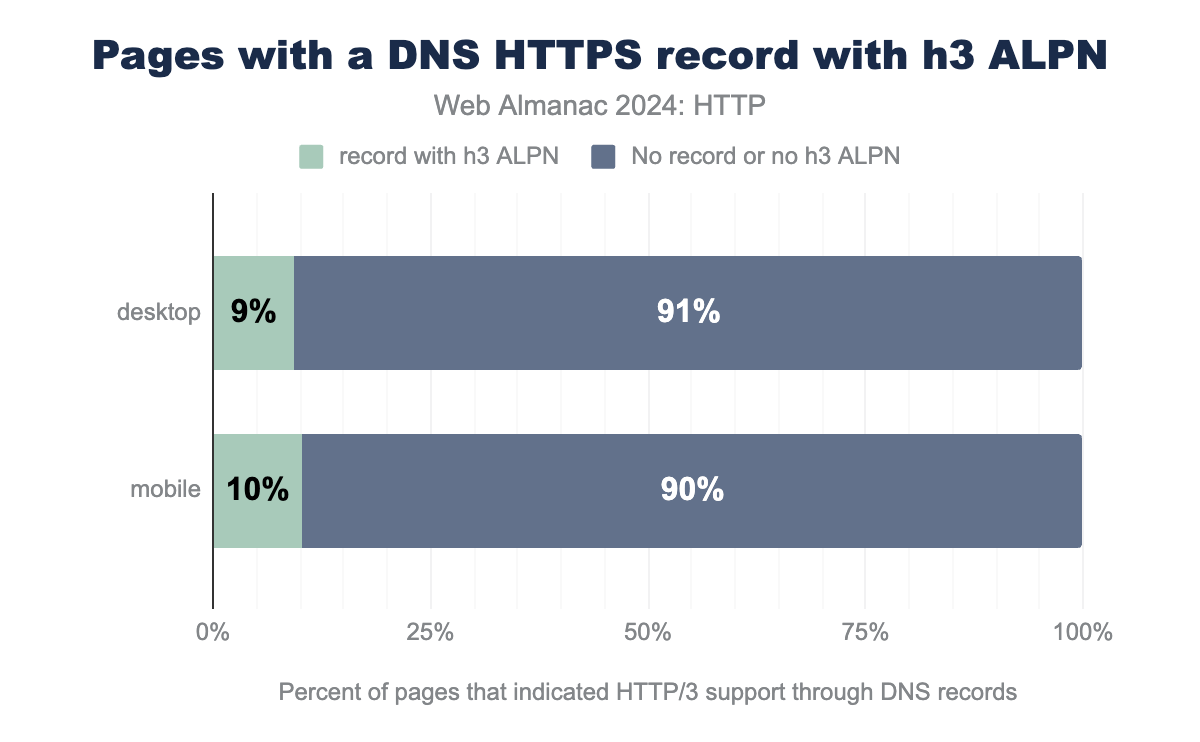

Let’s now take a look at how much we’ve seen the new DNS records being used in the wild in the Web Almanac dataset. Looking at the general use, we see that around 12% of both mobile and desktop pages have an HTTPS record of some kind defined. Not all of those include the h3 option in their alpn section however: that’s slightly lower at 9% (desktop) and 10% (mobile):

h3 ALPN token set, while 91% used either no DNS HTTPS record at all or one without the h3 ALPN token set. On mobile, 10% of pages used an HTTP/3-capable DNS HTTPS record.This means that 9-10% (or over 20 million) of all considered pages in our dataset indicate HTTP/3 support through DNS. However, this does not automatically mean that HTTP/3 is also actually used by the browser. As we showed in the first image of this chapter, only about 7% (desktop) to 9% (mobile) of pages were actually loaded over HTTP/3. This is definitely in the same order of magnitude as the DNS HTTPS adoption, but not quite the same.

This can have many different reasons, including: networks blocking the newer protocol, HTTP/3 somehow losing the “race” to a HTTP/2 connection (we’ll discuss this in the next section, Other considerations), the DNS HTTPS record being misconfigured, the DNS response for the record being delayed, the HTTP/2 connection being reused due to connection coalescing. Still, it shows that this newer/alternative method of indicating HTTP/3 support early in the page loading process has strong potential to improve upon the alt-svc approach! This is especially true for our Web Almanac methodology, as we confirmed that 99% of all page loads observed over HTTP/3 were indeed triggered by the presence of DNS HTTPS records (the 1% discrepancy is a bit weird though, and a good topic for future analysis).

It is also interesting to compare this to similar research done by Jan Schaumann in October 2023, who found that for over 100 million tested domains, only about 4% provided HTTPS records, which increased to a whopping 25%+ for the top 1 million domains on the Tranco list. He concluded that DNS HTTPS record adoption is “effectively driven by Cloudflare setting the records by default on all of their domains”. This would be in-line with our previous findings that it is the big CDNs that drive new feature adoption, so let’s see what our data says:

h3 DNS records |

CDN |

|---|---|

| > 60% | None (yet!) |

| 50% - 60% | Cloudflare |

| 2% - 50% | BunnyCDN, Alibaba |

| < 2% | Akamai, Amazon Cloudfront, Microsoft Azure, Fastly, Netlify, Google, Incapsula, Azion, Sucuri Firewall, Vercel |

| < 0.05% | Automattic, OVH |

We can indeed see that Cloudflare is clearly the leader of the pack here, setting h3 in the HTTPS DNS record for over 50% of its hosted sites. Most of the other large CDNs do seem to have some support and are testing the feature, but they rarely get above 2%. An interesting outlier here is Automattic, which had near universal HTTP/3 support via alt-svc, but only 0.04% for DNS HTTPS records. Outside this, of the 8.5 million pages not loaded via a CDN, only 0.46% had a DNS HTTPS record configured for HTTP/3 support, again reinforcing our conclusion that (for better or worse) CDNs are the ones driving adoption of cutting edge features at scale.

It will be interesting to track the use of DNS HTTPS and SVCB records in the coming years of the Web Almanac to both see how their adoption evolves, and how that will map to actual HTTP/3 use in the dataset.

Other considerations

In practice, there is even more complexity in the protocol selection/connection setup process used by modern browsers.

One example is an algorithm called Happy Eyeballs (yes, really!), which describes how to test for and choose from several different options. This is used to decide between HTTP/2 and HTTP/3, but also IPv4 and IPv6—for which it was originally invented. This algorithm typically “races” different connections against each other and then picks the “winner” to continue the page load on-which means that we sometimes will still see HTTP/2 even though HTTP/3 is supported, if HTTP/2 wins the race. This data is not yet tracked in our dataset, so we don’t really know how often this happens-though in practice this would also heavily depend on testing location and the network used.

Another example is the concept of connection coalescing (which they really should have just called “connection reuse” in my opinion), which says that browsers should prefer to reuse an existing connection instead of opening a new one. In practice, if two domains (a.com and b.com) share the same TLS certificate, the browser can (and often does) re-use an existing connection to a.com to fetch b.com/main.js. You can imagine the headaches this gives if a.com has HTTP/3 enabled and b.com does not… We did not yet analyze how often this happens in the Web Almanac dataset, but from personal experience debugging problems with this, I can assure you it’s definitely out there!

cdn.shopify.com that see both HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 connections to that domain.

Finally, browsers don’t always wait for an existing (HTTP/2) connection to be closed before opening a new (HTTP/3) connection; sometimes they try to switch much more agressively, even during an ongoing page load over HTTP/2! This can cause “hybrid” page loads, which makes interpreting Real User Monitoring (RUM) metrics and comparing HTTP/2 to HTTP/3 performance quite challenging. Measuring how often this happens in our dataset is a bit tricky, but we tried to get an idea by seeing how many domains had both HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 connections opened for them during individual page loads. We find a high dual-protocol usage especially for third parties, with for example connect.facebook.com seeing both HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 in the same page load 34% of the time, and cdn.shopify.com even switching in 96% of cases. It’s not always this high though, with www.facebook.com interestingly only seeing a switch on 12% of pages it’s used on, and various wp.com trackers showing only 1-6% (likely because only a few resources are loaded from these domains and there’s no time/need to switch). One caveat is that these switches are also potentially influenced by other factors, such as needing a new connection for CORS reasons or being used in an iframe. Still, I believe the data shows that those “hybrid” page loads are quite common and should be taken into account, even though it’s yet unclear which exact impact this has/can have on performance metrics like Largest Contentful Paint.

All of this just reinforces our story so far that there is a lot going on at the network layer nowadays, which makes everything more difficult, from properly judging real adoption from our dataset, to deploying the protocol yourself without CDN support, to correctly analyzing and debugging results from RUM data. While adoption of these newer features is steadily rising due to support from big deployments, it will probably level out relatively soon, taking a long time for smaller deployments and especially individuals to start using the newer protocols. Just like we still see a considerable amount of HTTP/1.1 out there, I expect HTTP/2 also won’t be going anywhere for quite some time.

Now that I’ve probably scared you away from ever looking into the internals of protocols ever again, let’s consider some higher-level features that allow you to nudge their behaviour without having to understand what ALPN or SVCB stand for.

Higher-level browser APIs

As we’ve seen in the first part of this chapter, the adoption of HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 are on the rise, and that’s a good thing (mostly). These new protocols implement a lot of performance and security best practices that have tangible benefits for end users. For developers however, the protocols and their features often remain a black box, as there are very few ways to tune them directly. You basically just tick a box on your CDN or server configuration, and hope the browser and server get it right.

However, there are a few higher-level features (such as image lazy loading, async/defer javascript attributes, Resource Hints, the Fetch Priority API), that allow us to influence what happens on the network to an extent. Even though these are not technically always directly tied to HTTP as a protocol, they can have a major impact on how some protocol features (such as connection establishment and resource multiplexing) are used in practice, so we discuss some of them in this chapter.

Resource Hints

Firstly, there are the “Resource Hints”, a group of directives that can be used to guide the browser in various network-related operations, from setting up (parts of) a network connection, over loading a single resource, to doing fetches of entire pages ahead of time. The main ones are dns-prefetch, preconnect, preload, prefetch, and modulepreload. There was also a prerender option which had a bit of a hard time finding its place in the ecosystem, and that use case now moved mostly to the new Speculation Rules API.

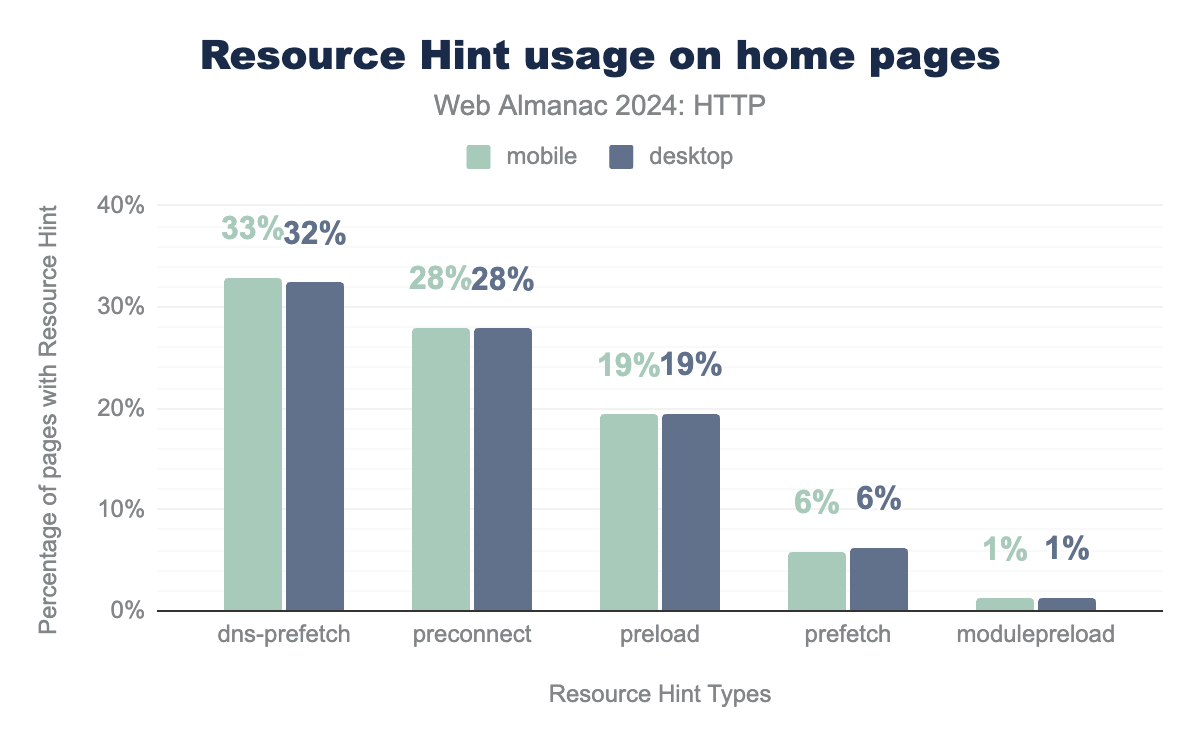

dns-prefetch is used on 33% of all mobile pages (32% for desktop), preconnect is used on 28% of pages (desktop and mobile), preload is used on 19% of pages (desktop and mobile), prefetch on 6% and modulepreload on 1%.These directives have found an impressive uptake over the years, with over 30% of all pages in our dataset using dns-prefetch, 28% utilizing preconnect and preload closing in on 20%.

Personally, I find the high usage of dns-prefetch somewhat surprising, as in my opinion you should almost always use preconnect instead, as it does more (establishing the full connection including TCP+TLS or QUIC handshakes) with negligent overhead, and is also very well supported. Furthermore (though purely anecdotally), I often see developers use both dns-prefetch and preconnect right after each other for the same domain, which is almost completely useless nowadays, as preconnect automatically includes a DNS lookup as well and is well supported as noted. Still, an overall high use of these directives is good for performance, as it helps hide connection setup latency to subdomains or third-party domains that might host important assets, such as images or fonts.

Some (at least to me) unexpected yet good news is that very few pages seem to overuse these hints. In general, you should rely on the browser to get things right itself—through features like the preload scanner. You should only use the Resource Hints sparingly for those cases where you know the browser doesn’t have enough information—for example, when the 3rd party domain/resource is not mentioned in the HTML directly but only in a CSS/JS file. And this is exactly what most people have been doing (yay!): even at the 90th percentile, pages will only use 3 dns-prefetch, 2 preconnect and 2 preload directives, which is great!

Specifically for preload, we also looked at how many resources are preloaded in vain and not actually used on the page. The results were again quite encouraging: less than 4% of desktop pages uselessly preload 1 or 2 resources, and less than 2% have 3 or more unused preloads!

Still, even though most pages seem to get it right, it’s always fun to look at some of the worst offenders. There will always be pages which include way too many hints, usually either due to misconfiguration or a misunderstanding of what the features are supposed to do.

For example, one page had a whopping 3215 preloads! Looking more closely however, it was clear that they are preloading the exact same image over and over again, most likely due to a misconfiguration of their framework/bug in their code.

The second worst offender took it easy with “just” 2583 preloads, all of different versions/subsets of various asian fonts from Google Fonts. Finally, one page preloads an amazing 1259 images, turning them into a “smooth” scrolling background animation; arguably, you could say here preload is actually used in a good way to improve the intended effect, though I wouldn’t recommend it in general!

Luckily as well, some of the worst problem cases in our dataset have been fixed since our June 2024 crawl, such as a “Sexy Pirate Poker” site going from 2095 to just 14 preloads (steady as she goes, mateys!).

A final silver lining is that no pages had more than 1,000 dns-prefetch or preconnect directives. The worst ones utilized a measly 590 and 441 domains respectively.

In general, Resource Hints remain powerful features that should be used sparingly to great effect, something which most developers seem to understand. Let’s now take a deeper look at preload specifically though, as it is one of the more powerful hints that is widely supported, and it can have a large impact on performance, both positively and negatively (if used incorrectly).

Preload

Generally speaking, preload should mainly be used to inform the browser of resources that are not linked directly in the main HTML document but that you as a developer know will be important/needed later—such as things loaded dynamically with JS fetch() or CSS @import and url(). Preloading them allows the browser to request them earlier from the server, which may improve performance—but can also degrade it, if you try to preload too much.

Good concrete examples include fonts (which are typically loaded via CSS and only requested by the browser when it actually needs them to render text), JS submodules or components imported dynamically, and (Largest Contentful Paint, LCP) images that are loaded via CSS or JS (which you probably shouldn’t do in the first place, but sometimes there’s no other option).

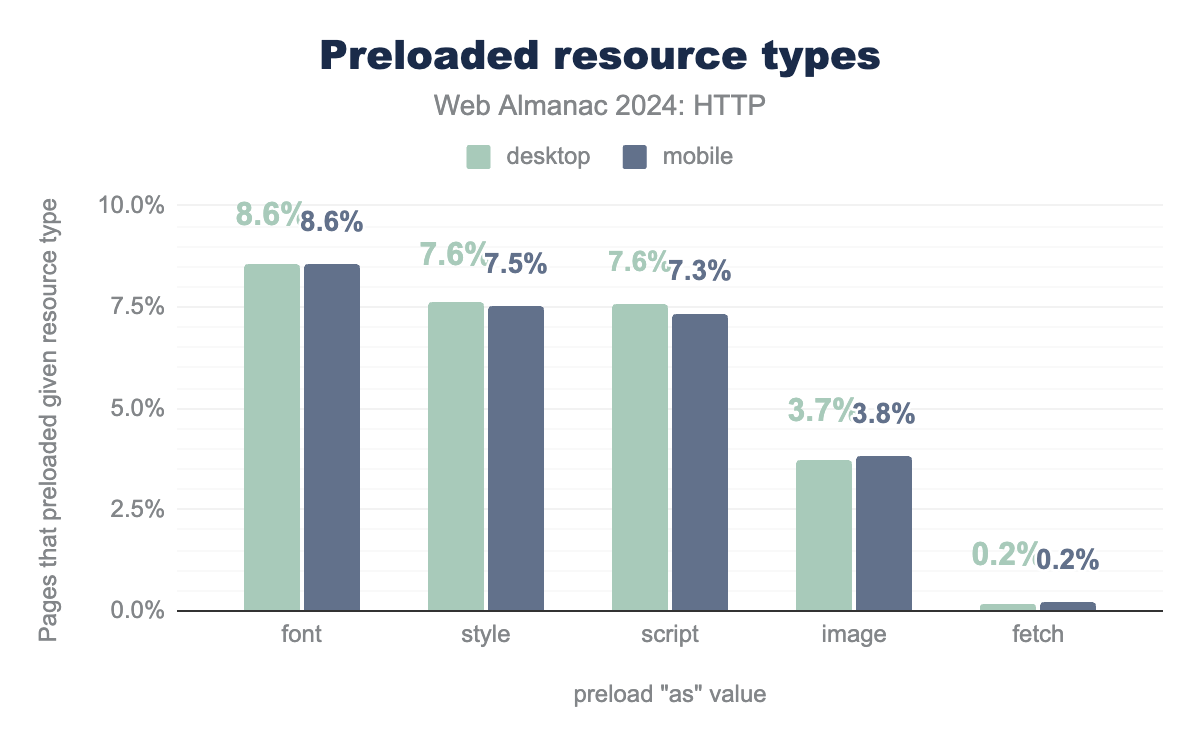

As we saw above, about 20% of all pages utilize preload, and because you have to explicitly indicate which type of resource you’re trying to preload with the as attribute, we can get some more information on how exactly sites are using it.

preload for 5 specific resource types. Fonts are preloaded on 8.6% of all desktop and mobile pages, stylesheets are preloaded on 7.6% of desktop and 7.5% of mobile pages, script preloads are found on 7.6% of desktop and 7.3% of mobile pages, images are preloaded on 3.7% of desktop and 3.8% of mobile pages, and fetch calls are preloaded on 0.2% of both mobile and desktop pages.As expected, fonts are the most popular target for preloads, occurring on about 8.6% of pages.

Somewhat unexpected however was the high use of preload for stylesheets and scripts. These could conceptually be useful, but that would mean over 7.5% of pages should probably reduce their critical path depth, if they need preload to speed that up. In practice people often misuse the feature by preloading resources right before they’re mentioned in the HTML; say by having a <link rel=preload> for style.css the line above the <link rel=stylesheet> for the same file, which doesn’t really do anything.

A worse problem I’ve seen is that people preload their async and defer JS files, often those that are loaded via a <script> tag at the bottom of the <body>. This is not as harmless as it might seem, as these preloads can end up actively delaying other resources—such as actual render blocking JS and important images. This is because the browser doesn’t know these scripts will be tagged as async/defer when they’re actually loaded, so it defaults to loading them as if they’re render blocking scripts with a high priority!. We didn’t run the queries to see how many of the 7.5% of pages misuse preload like this, but from my personal experience, it could be pretty widespread.

In contrast, while perhaps too many async/defer JS scripts are being preloaded, potentially too few JavaScript modules (<script type=module>) are benefiting from this hint. While about 9.6% of all desktop pages already use JS modules (which I found impressively high), only about 13% of those (1.24% of all pages) also preload at least one module. I would have expected this to be a bit higher, since the JS modules mechanism has extensive support for dynamically loading code, which could benefit from preloads to improve performance.

Potentially, this is because—due to annoying CORS-related reasons—you actually need a special flavor of preload specifically for JS modules, (predictably) called modulepreload. It could be that too few people are aware of this special type to use it, or just that JS modules are too new to have been fully figured out, or because people aren’t really using dynamic imports or deep import trees in practice; future Web Almanac analysis will have to tell.

A different, more positive note is that fewer than 4% of pages preload an image, which I had expected to be a lot higher, as 79% (desktop) to 69% (mobile) of pages have an LCP element that’s an external source URL such as an image.

Similar to CSS, it is usually pretty useless to preload an image that’s already linked to in the HTML directly (for example as an img or picture tag), as the browser typically discovers the image early enough even without preload. Luckily, it seems that developers are not making this mistake often: in our dataset, of all the pages that have an <img> as their LCP element (46% on desktop, 41% on mobile), less than 1% actually preload that image (0.7% desktop, 0.9% mobile).

In contrast, there are images that can benefit from preloading, for example those LCPs loaded via CSS as background images, as those are typically only discovered late. In our dataset, 27% of desktop pages and 25% of mobile pages have a <div> as their LCP element, which often means it has a CSS background image. Out of those cases, 2.3% (desktop) and 2% (mobile) actually preload the LCP resource url, more than double than was the case for <img>! While that’s a good thing, in my opinion people are actually potentially underutilizing preload for this use case—though note that you should really only preload the LCP background image, not others!

The astute reader might have noticed that the total amount of pages preloading images (~3.8%) is quite a bit higher than those preloading the LCP element (~1.3% total), which makes me wonder which other images people are preloading then and why…; another thing best left for future analysis!

Finally, as with the general Resource Hints, it’s also interesting to look at outliers and obvious mistakes. For preload to function, you MUST set the as attribute, and it can only be set to a select few types: fetch, font, image, script, style, track. Anything else will cause the preload to be in vain. As such, it’s interesting to see over 17,000 pages (about 0.11% overall) use an empty value, with 0.03% - 0.01% utilizing invalid (though probable) values like stylesheet, document, or video. Other noteworthy (luckily much less frequent) values include: the fancy Cormorant Garamond Bold, the cool slick, the spicy habanero and the supercalifragilisticexpialidocious Poppins.

103 Early Hints

Resource Hints are typically conveyed through <link rel=XYZ> tags inside the page HTML’s <head>. However, though you may not know this, Resource Hints can also be sent in the HTTP response headers for the HTML page instead (albeit with a slightly different syntax). In fact, I’m pretty sure most of you don’t know this, since only about 0.04% of all pages (or about 5,500 desktop home pages) utilizes this option—compared to about 20% that use the HTML tags. This is not too surprising though, as there are only very few cases in which the HTTP header option is easier or better than the HTML tag option in my opinion.

However, this might be changing a bit, with the (relatively) new 103 Early Hints feature. This mechanism is sometimes called the rightful successor to HTTP Server Push. It allows a server to send back an intermediate 103 response (part of the HTTP 1XX range of status codes) before the actual final response for a request (say a 200 OK or 404 Not Found).

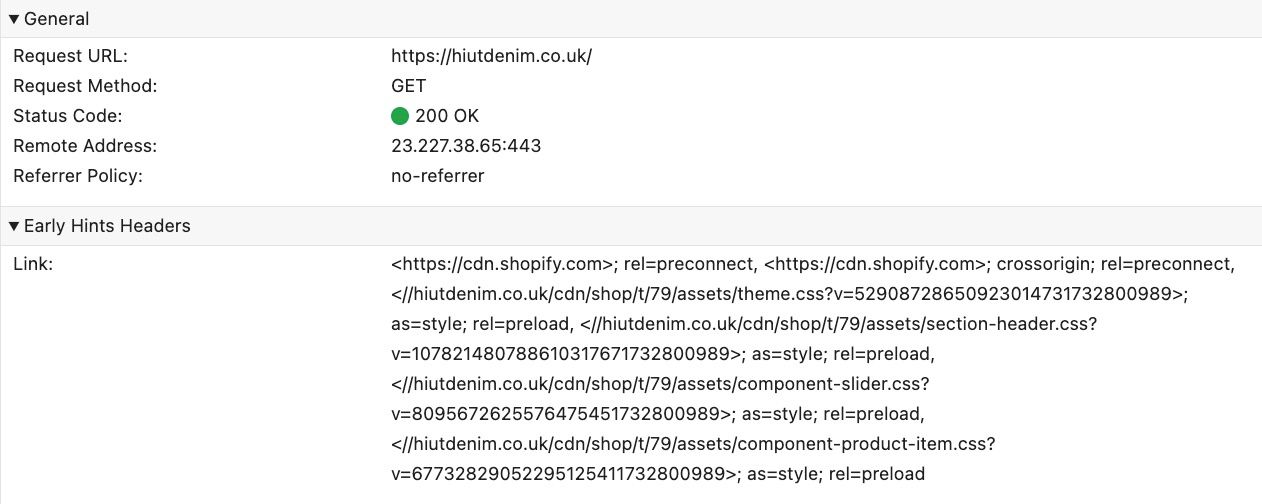

This is especially useful in CDN setups where the HTML is not cached at the CDN edge. In that scenario, the CDN can very quickly send back a 103 Early Hints response to the browser, while it forwards the request for the HTML to the origin server. This 103 response can contain a list of preconnect and preload Resource Hints (encoded as HTTP response headers), which the browser can start executing while it is still waiting for the final HTML response to come in.

preconnect to two shopify-related domains, and preload 4 CSS files.If everything goes well, the connections to external domains are ready and the preloaded resources are in the browser’s cache by the time the HTML comes in, providing an impressive performance boost!

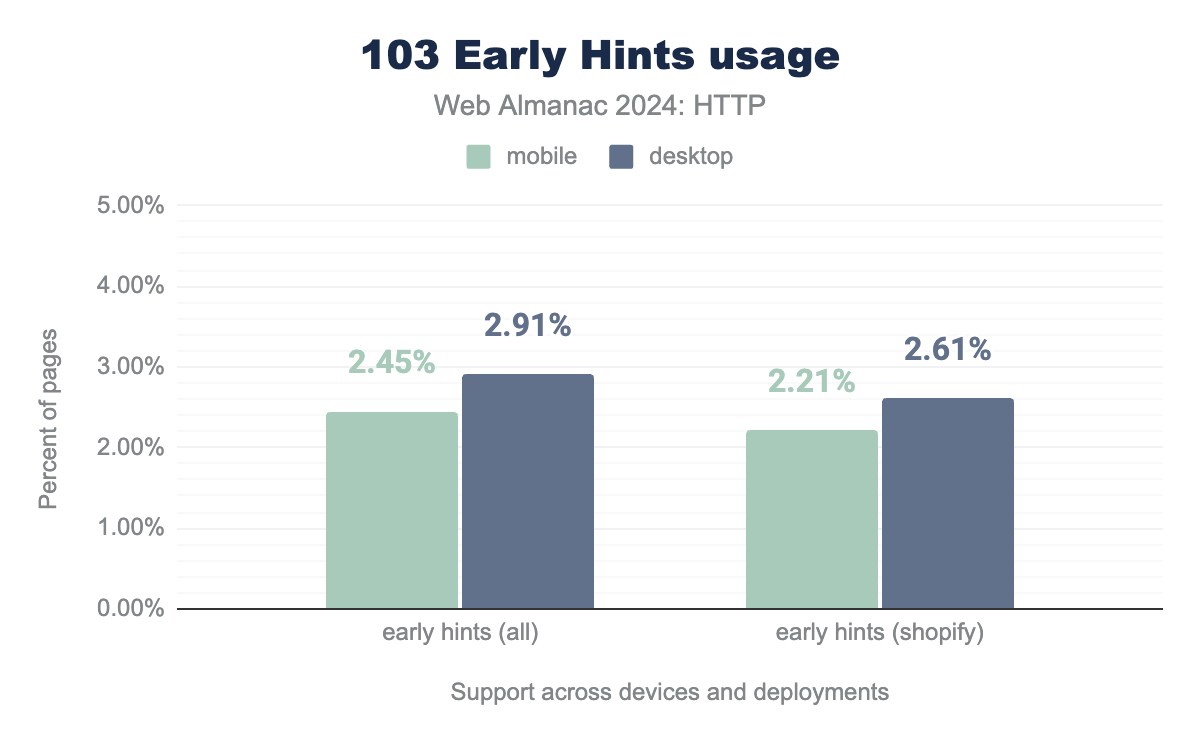

Disappointingly though, 103 Early Hints adoption has not increased a lot since our first look in 2022: from 1.6% of all desktop pages then, to just 2.9% this year. This is not incredibly surprising however, since properly configuring this feature is not easy, and getting full benefits from it typically requires using a CDN or a similarly distributed deployment.

Support has also been somewhat spotty, with Safari and Firefox only adding support recently (with Safari only allowing preconnect), it having been disabled for a while on Cloudflare, and the Akamai CDN only making it generally available in July this year. Still, I would have expected the uptake to be a bit higher, given that Cloudflare has had the feature available even for its free customers since 2022.

Staggeringly, we see that an overwhelming majority of Early Hints comes from just one deployment: Shopify (a Cloudflare customer) accounts for 90% those 2.9% of desktop pages that support Early Hints. This means that only about 39,000 non-Shopify desktop home pages employed the new feature. As such, it’s difficult and not very useful to draw broad conclusions about its real potential based on what we see in the Web Almanac’s dataset.

Still, there are a few interesting trends (mostly from Shopify’s deployment), including that the amount of preconnects is pretty much stable from the 10th up to the 90th percentile (usually preconnecting to https://cdn.shopify.com twice, once with and once without crossorigin). Preload on the other hand is lower at 1 at p75, increasing to 2 at p90.

Interestingly, stylesheets are the most preloaded resource type in Early Hints, about 4x as much as scripts. While fonts were the most popular for preloads in the HTML, here they are the least popular, coming even behind images. This I find quite weird, since in my opinion fonts are still excellent targets for preloading even in Early Hints, while images should probably be avoided, as preloads in Early Hints currently don’t support responsive images (preloads in the HTML do of course, don’t worry)!

In conclusion, while 103 Early Hints is still somewhat absent in our dataset, I feel this will improve over time, as more deployments support it, as it becomes easier to configure—for example, with automated Early Hints—and as more people become aware of its potential!

The Fetch Priority API

While the Resource Hints discussed above can influence when a connection is opened or when a resource is requested, they don’t really say much about what happens after that: How is the connection used? How are the resources downloaded? That is the purview of other features, among them the Fetch Priority API (previously called “Priority Hints”), which helps control how resources are scheduled on HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 connections.

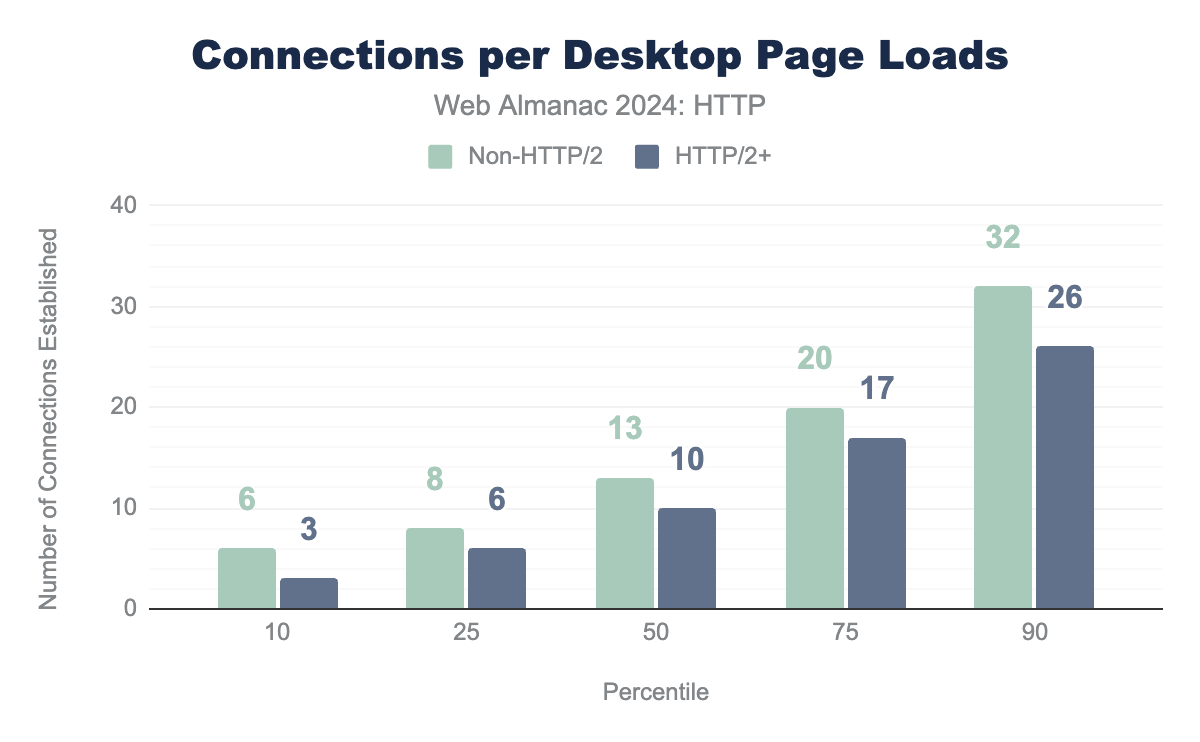

One of the main reasons to switch from HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 is that you need fewer connections. On the newer protocols, many resources can be “multiplexed” onto a single connection—requested and loaded concurrently—while on HTTP/1.1 you have to open multiple parallel connections to get a similar effect. As each connection has a certain overhead associated with it (TCP+TLS/QUIC handshakes, some memory at the server, competing congestion controllers, …), setting up and maintaining fewer connections is more efficient.

The differences here are a bit less clear than a few years ago though; in 2021, there was a 4 connection difference at p50 and p75 between the protocol versions, now this has shrunk to 3—potentially due to aspects like HTTP cache partioning, crossorigin woes or perhaps more 3rd parties being used. It is still clear however that the new protocols indeed reduce the connection count and improve efficiency and at p10, only half as many connections are needed!

However, now that we have more resources sharing a single underlying connection, that means that we somehow need to decide what gets downloaded first as we typically don’t have enough bandwidth to just download everything in one big parallel flow. This “resource scheduling” is governed by a “prioritization mechanism” in HTTP/2 and HTTP/3. How this really works under the hood is a bit too complex to really dig into here however, so we will focus on the basics you need to understand the Fetch Priority API (more details can be found in blogposts, talks, academic papers and of course, web.dev).

In general, the browser will assign each request a priority: an indication of how important it is to the page load. For example, the HTML document and render-blocking CSS in the <head> might get highest priority, while less critical resources (such as images in the <body> or JS tagged as async or defer) might get low. When the server then receives multiple requests from the browser in parallel, it knows in which order to reply: from highest to lowest priority, and following the request order for resources with the same priority value.

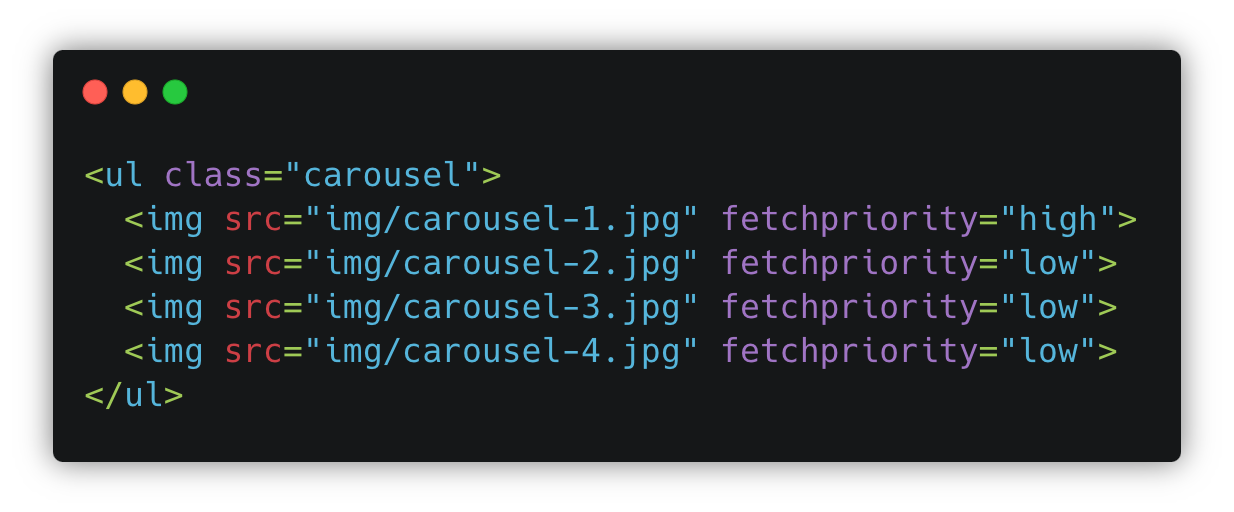

high to increase priority of the first image in an image carousel, while using low to decrease the priority of the other images that are hidden at the start.Browsers use a complex set of heuristics (“educated guesses”) to determine the priorities of the resources—based on factors like their position in the HTML document, their type, and loading modifiers such as async/defer. This however also sometimes means the browser gets it wrong, or it simply does not have enough information to make a smarter choice.

A good example here are LCP images: the browser can’t really accurately predict which image will end up being the LCP element just from the HTML. As such, it generally requests all images at the same priority, in discovery order; so if your LCP image is lower in the HTML (below say some images in the menu that’s hidden by default) it will end up loaded later than it probably should.

It is for these reasons that we now have the Fetch Priority API! It lets us tweak/nudge the browser’s default heuristics so it assigns high(er) or low(er) priority values to individual resources—meaning they get loaded earlier/later than they otherwise would. This is done by adding the fetchpriority attribute with a value of either high or low to a resource.

It can be used on many things, not just images but also <script> and <link> tags and even fetch() calls (there, it’s just the priority attribute though, because naming things is hard). The Fetch Priority API has been supported in Chrome for a while now, with Safari adding support late last year, and Firefox landing the feature in October 2024. As such, let’s see how it’s being used in the wild!

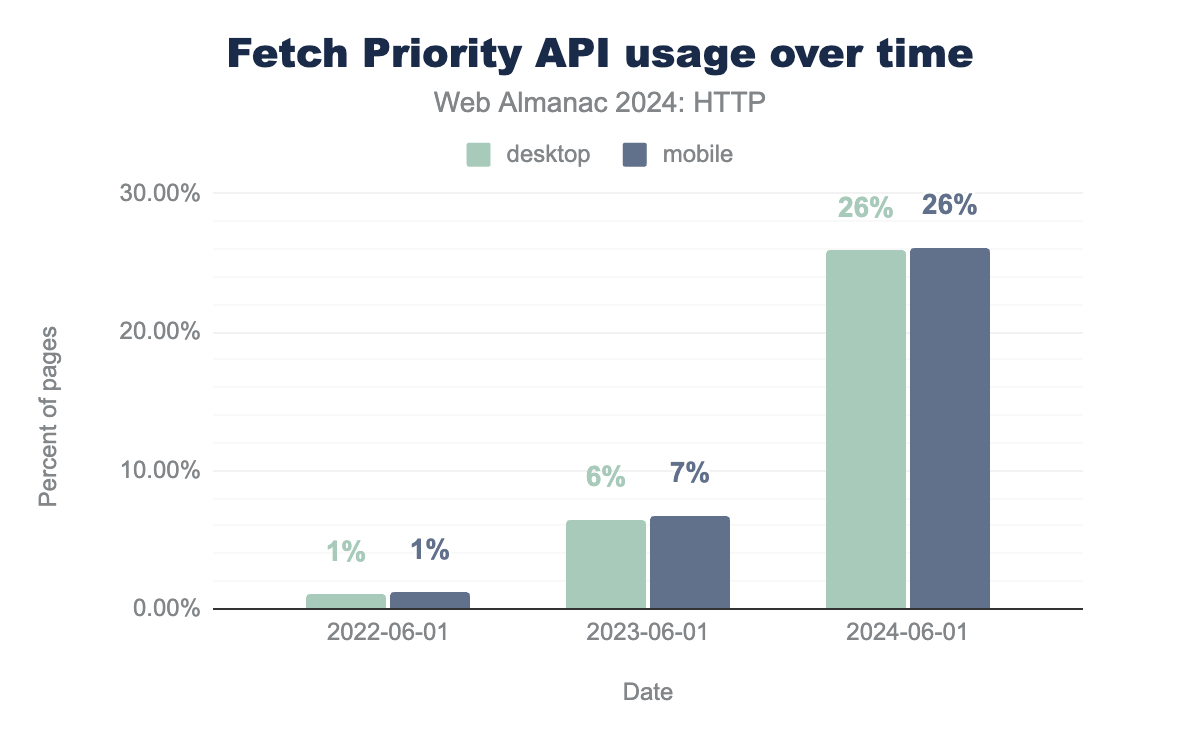

Fetch Priority adoption has positively soared in 2024! Going from around 7% in 2023 to 26% of pages in 2024 using at least one fetchpriority attribute is truly a stunning result. Many pages even use more than 1 instance, with the 90th percentile showing 2 uses per page, up to 9 for desktop pages at the 95th (just like with Resource Hints there are of course also people overdoing it, with one page using it an incredible 2382 times!).

<img>-tag with fetchpriority=high as their LCP element

Let’s look at how fetchpriority is being used specifically for LCP images since that is one of the main motivating use cases for this new feature. For example, for those 46% of desktop pages that have an <img> element as their LCP, a good 12% (or 5.6% of all desktop pages) also tag it as fetchpriority=high; This could/should arguably be (much) higher, but luckily only 0.14% tagged the LCP <img> as fetchpriority=low, so I’ll take it!

Sadly, this is offset by the fact that over 16% of desktop pages does still lazy load their LCP image, which you should really never do… luckily, only 4,500 pages were written by cats who don’t know whether they want to stay in or go outside (and thus have an LCP element with both loading=lazy AND fetchpriority=high, which is just weird).

We also looked into which initial priority LCP images were requested with in general. By default, images in Chrome have low priority, unless they’re one of the first 5 images in the HTML, in which case they get medium priority. Images can get promoted to high priority if the browser determines early on they’re in the viewport or, as you’d expect, if fetchpriority=high is used.

Again looking at all the desktop pages having an <img> element as their LCP, we see that 42% starts at low (so they’re not even in the top 5!), 45% are medium (a bit better) and just 12% get requested as high (almost entirely due to fetchpriority=high). As such, despite the impressive and rapid uptake of fetch priority in the past 2 years, there is still a large window of opportunity to do some “low hanging fruit” optimizations for many pages by tagging their LCP as fetchpriority=high—after first removing loading=lazy, of course!

Preload again

The fetchpriority attribute can also be used on <link> tags. That’s not only useful for CSS stylesheets, but also for (you guessed it!) <link rel=preload>. So even though we’ve already spent a lot of time on preload above, let’s revisit it here for some added nuance, as fetch priority really makes a difference here too.

Conceptually, preload by itself doesn’t/shouldn’t change a resource’s priority, only when it’s discovered and therefore requested by the browser. This is true for images for example : even if you preload your LCP, it will still be low priority, unless you also add fetchpriority=high to your preload, which is often unexpected for people!

In other cases, preload DOES seem to “change” the priority. For example, the case when preloading async/defer JS (as discussed above as well), where the browser will assign them high priority instead of low because it doesn’t get enough context from the preload. In these cases, it can be very useful to use fetchpriority=low on the JS preload, to “correct” the browser heuristics to where we know they should be.

fetchpriority=high set that are for images

We looked at how people are combining preload with fetchpriority in our dataset. Of all desktop pages with preloads using fetchpriority (about 2% of all desktop pages), an impressive 73% are for images with fetchpriority=high. While this can indeed be a good idea for LCP images, it does have some rough edges and can be a footgun if used incorrectly at the top of the <head>, actually delaying JS lower down the document. For this reason, nowadays I even recommend just not preloading the LCP in favor of just having it in the HTML with fetchpriority=high on the <img> directly.

On the other end, 16% of these preloads are for scripts with fetchpriority=low, indicating at least some webmasters (what is this, 2005?!) are aware of potential issues with async/defer there and try to prevent them. For styles, people don’t really seem to know what they want (or use cases are diverse), as 3% is loaded as high and 5% as low. Note that a lot of these nuances are also discussed on web.dev, so make sure to read up on things there.

Finally, an interesting 0.06% of pages tries to preload things with a highest value for fetchpriority, which is not supported (you can only use high or low)!

Conclusion

In summary, despite HTTP being invented early in the 1990s, its third version is still making waves on the Internet, finding a steadily increasing adoption that should reach 30% soon. This is aided by the introduction of some new capabilities, such as DNS HTTPS records, which make discovering and using HTTP/3—and other newer protocol features—faster and easier.

While the newer protocol versions are typically presented as a black box to developers (indeed, we can’t even consciously choose to use HTTP/3 in fetch()), some high-level features exist that allow tweaking the underlying behaviours. For example, Resource Hints have become more powerful now they can be used inside 103 Early Hints responses, allowing browsers to preconnect and preload even before the HTML is known. Complementary, the Fetch Priority API can help improve browser heuristics that decide in which order resources are downloaded from a server on HTTP/2’s and HTTP/3’s heavily multiplexed connections. Developers have found their way to some of these features quite easily (with especially Fetch Priority rising to a 25%+ usage share in a mere 2 years), while remaining hesitant on some others (at less than 3% usage share, 103 Early Hints seems difficult to use or just unknown to many).

Still, there remain challenges ahead. CDNs are the outsized driving force between the fast adoption of many of these new technologies (85% of all HTTP/3 traffic was served through a CDN). This is both “good” and “bad” for the ecosystem in my opinion. Good because they battle-test new technologies quickly and give them a huge market share right out of the gate, ensuring good chances for survival. Bad because this causes the web to become ever more centralized around a few large companies (54% of all requests in our dataset were served from a CDN), with people not using them being at risk of being left behind.

This goes hand in hand with the increasing complexity of how the web works at the lower layers. Protocols like HTTP/3 are complex to understand, let alone deploy, but even the “simpler” high-level features can be difficult to really apply correctly in practice (the high amount of preloaded scripts is somewhat concerning). There is plenty of potential for misuse and shooting yourself in the foot and not everything is as well documented as it could be (the 16% of pages lazy loading their LCP image is a testament to that).

Still, I see a clear silver lining here. While it is my job to look for the mistakes people make (so I can help fix them!), I was pleasantly surprised to see that most of the obvious mistakes are in fact NOT as widespread as they sometimes seemed from personal experience. Let’s hope it remains that way as these newer features find even further adoption on the wider web. Hopefully, as developers become more familiar with the underlying features of the network protocols, some of the inherent complexity stops being a barrier to adoption, and even HTTP/3 can move beyond its CDN roots. Let’s work together to make that happen!