メディア

はじめに

画像と動画はウェブのあらゆる場所に存在しています。しかし、これらがウェブページにエンコードされ埋め込まれる方法は驚くほど多様で複雑であり、ベストプラクティスも常に進化しています。Web Almanacは、この複雑さと私たちがそれをどのように管理しているかを確認する機会を提供し、ウェブ上のメディアの現状、これまでの進化、そして—もしかしたら—今後の方向性についての広範な視点を与えてくれます。さあ、始めましょう!

画像

最も一般的なメディアタイプである画像から始めましょう。画像のないウェブページを見ることはどれくらいありますか?私たちにとっては非常にまれで、もし画像がなければ、おそらくオタクな開発者のブログを見ているのでしょう。

1,000万以上のスキャンおよび解析されたページのうち、99.9%が少なくとも1つの画像をリクエストしたことは驚きではありません。

ほとんどすべてのページが、背景画像やファビコンだけであっても、何らかの画像を提供しています。

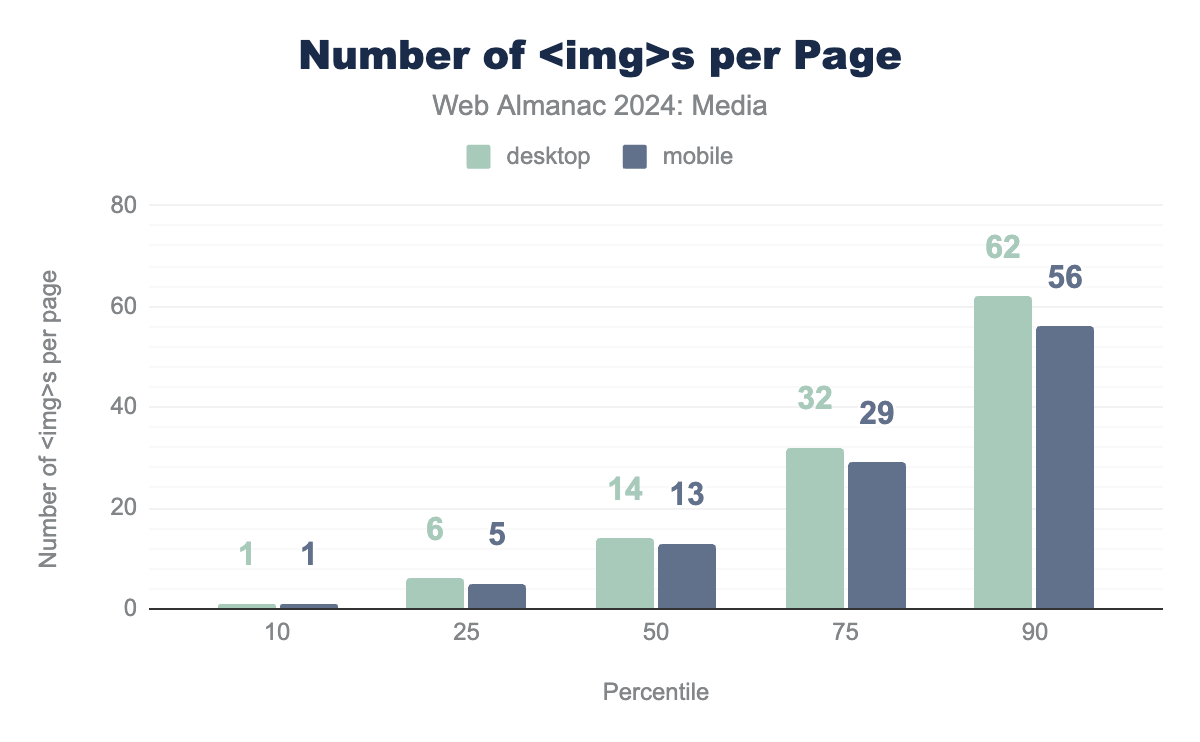

1ページあたりに見つかった<img>要素はいくつありましたか?

<img>要素の数。

モバイルページの中央値は13個の<img>要素を含んでいます。そして90パーセンタイルでも、ページは「わずか」56個の<img>しか含んでいません。今日のウェブのビジュアル的な性質を考えると、これは妥当なようです。

1ページに56個の<img>が多いと思うなら、モバイルクローラーが2,000個以上の<img>要素を含むページを見つけたとは言わないほうがいいでしょう。

<img>要素数(モバイル)。

画像は単に普及し豊富なだけではありません。ほとんどの場合、ユーザー体験の中心的な部分でもあります。それを測定する一つの方法は、ページの最大コンテンツフル描画(LCP)に画像がどれだけ関与しているかを確認することです。

ウェブ上での画像の重要性を強調しすぎることは難しいです。では、私たちが扱っているものを調査してみましょう!

画像リソース

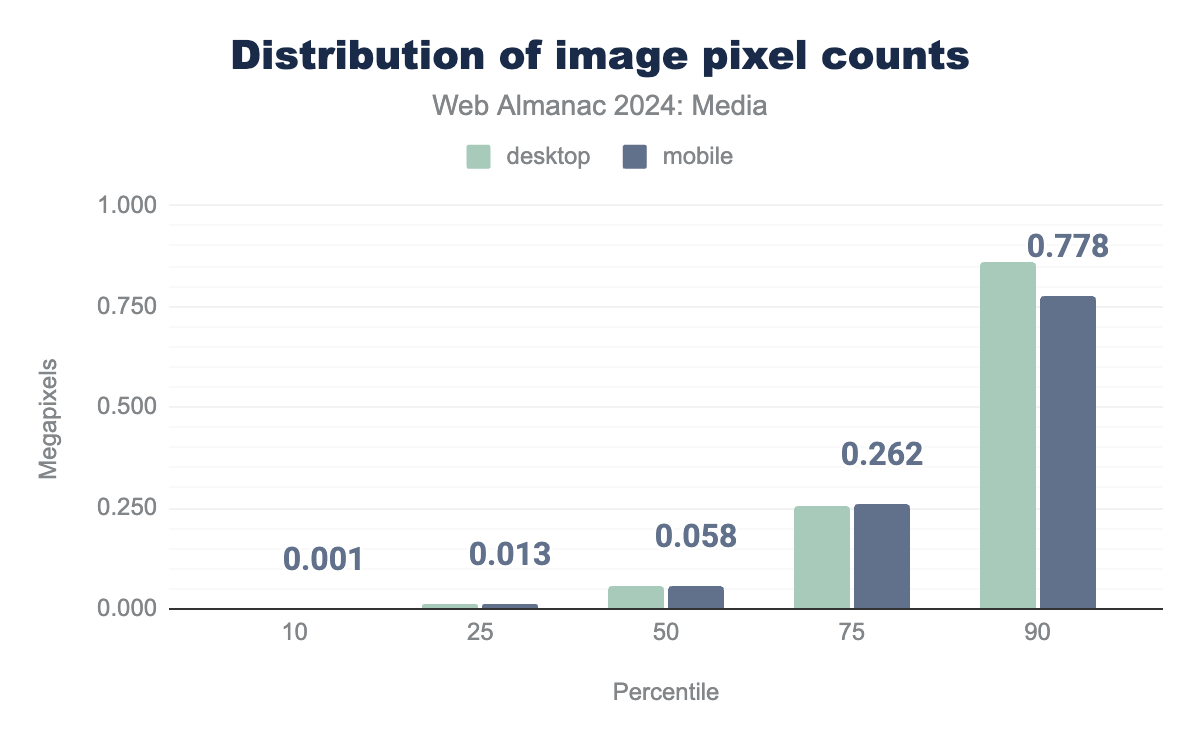

リソース自体から始めましょう。ほとんどの画像はピクセルで構成されています(ベクター画像は一旦脇に置いておきましょう)。ウェブ上の画像は一般的に何ピクセルあるのでしょうか?

おそらく驚くべきことに、多くの画像はたった1ピクセルだけで構成されています!

単一ピクセル画像

| クライアント | 1×1画像 |

|---|---|

| モバイル | 6.4% |

| デスクトップ | 6.0% |

<img>要素によって読み込まれたリソース。

1×1ピクセルの画像は、キャプチャされた画像リクエストの約6%を占めています。これらはおそらく、昨年のメディアの章で発見されたトラッキングビーコンやスペーサーGIFでしょう。そして振り返ってみると、嬉しいニュースがあります:1ピクセル画像の割合は2022年から1ポイント完全に低下しています。おそらく古い習慣が徐々により新しく優れた代替手段に置き換えられているのでしょう。

画像の寸法

ここで1×1よりも大きな画像に目を向けてみましょう。それらはどれくらいの大きさだったのでしょうか?

Web Almanacのモバイルクローラーはまったく成長していないにもかかわらず(360pxの幅のビューポートで、デバイスピクセル比3xでページをレンダリング)、0.058メガピクセルの中央値の画像は、前回調査した時よりも約25%大きくなっています。参考までに、正方形のアスペクト比では、0.058メガピクセルは約240×240になります。

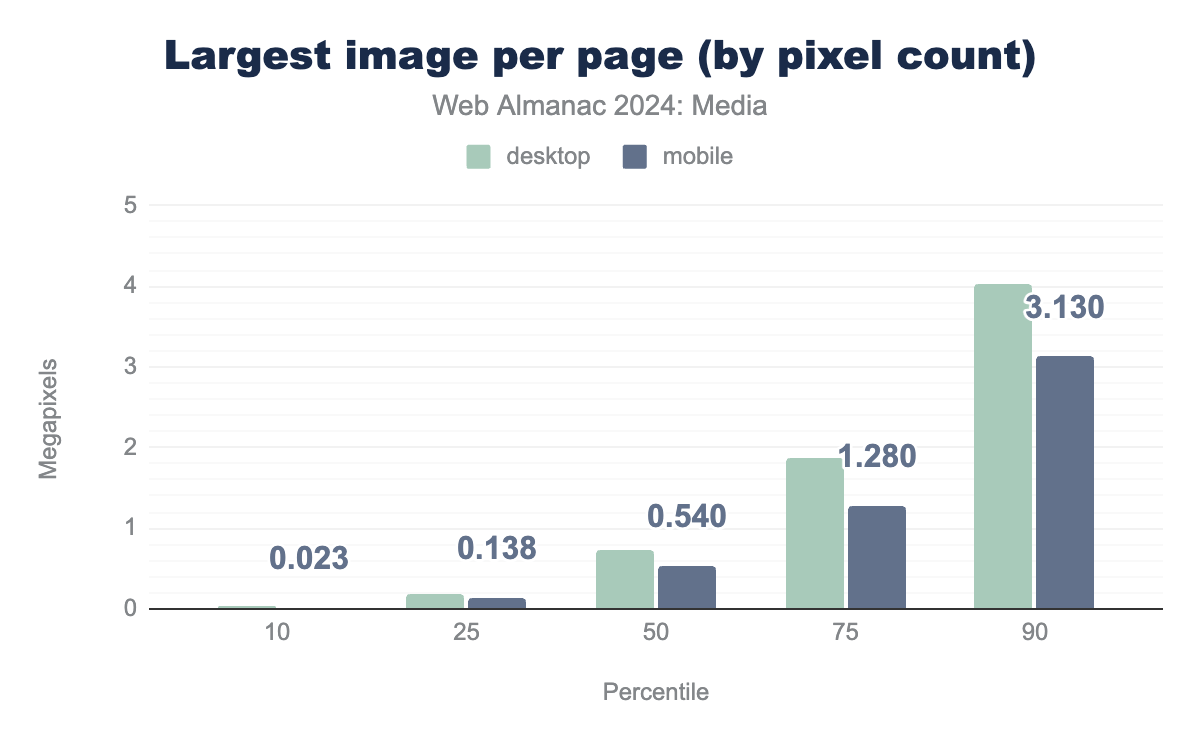

ほとんどのページには、中央値の画像のピクセル数の約10倍のピクセルを持つ画像が1つあります:

正方形のアスペクト比では、0.54メガピクセルは約735×735になります。モバイルクローラーのビューポートと密度を考えると、多くのページに高密度で全幅表示される「ヒーロー」画像が1つあるのはかなり可能性が高いです。

それよりも大きな画像を送信しているページの50%に関しては、ほぼ確実にモバイルクローラーが実際に表示できるよりも多くのピクセルを送信しており、適切に書かれたレスポンシブ画像のマークアップでそのムダを防ぐことができたはずです。しかし、これについては後ほど詳しく説明します。

画像のアスペクト比

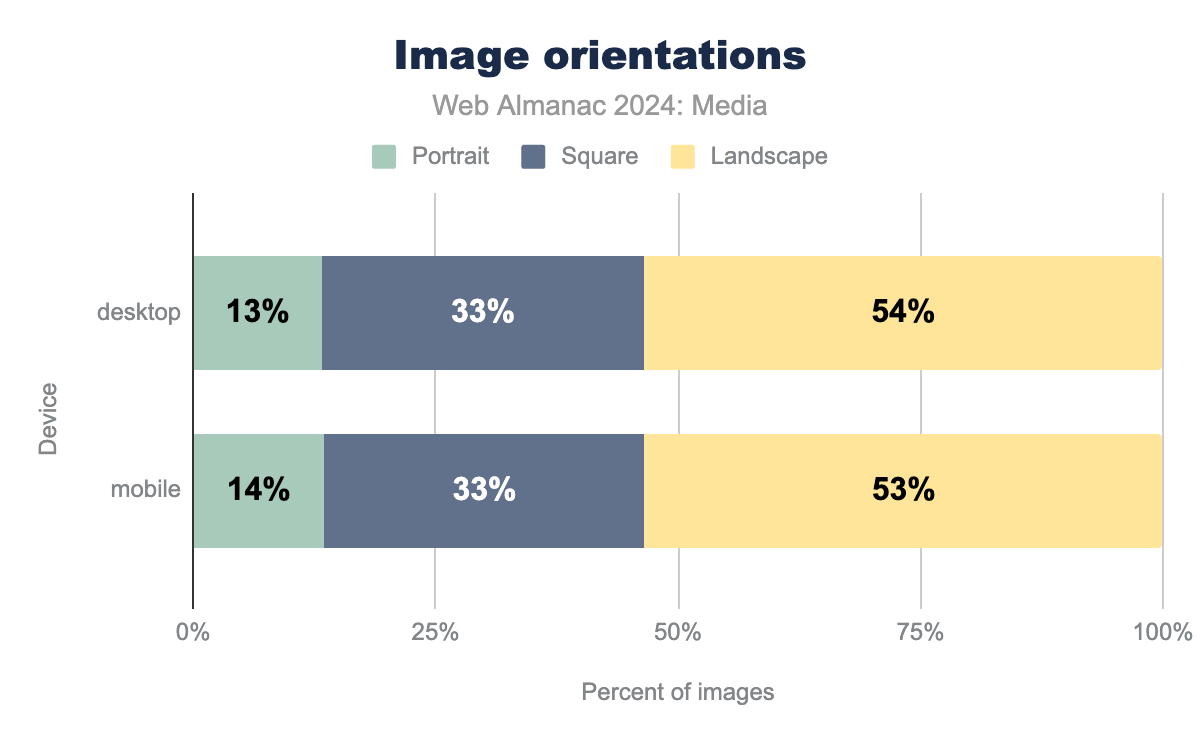

ウェブ上の画像のサイズについてある程度理解したところで、それらの形状はどうなっているのでしょうか?

ほとんどの画像は縦よりも横幅が広く、8分の1だけが横よりも縦が長く、完全に3分の1が正確に正方形です。正方形は断然、最も人気のある正確なアスペクト比です:

| アスペクト比(幅 / 高さ) | 画像の割合 |

|---|---|

| 1:1 | 33.2% |

| 4:3 | 3.5% |

| 3:2 | 2.9% |

| 2:1 | 1.8% |

| 16:9 | 1.6% |

| 3:4 | 1.1% |

| 2:3 | 0.8% |

| 5:3 | 0.5% |

このデータは2年前とほとんど変わっていません。依然としてデスクトップベースのブラウジングへの偏りを示しているようです—クリエイターは縦向きのモバイル画面を大きく美しい縦向きの画像で埋める機会を逃しています。

画像の色空間

特定の画像内で可能な色の範囲は、その画像の色空間によって決まります。ウェブ上のデフォルトの色空間はsRGBです。画像が別の色空間を使用していることを示さない限り、ブラウザはsRGBを使用します。

画像に明示的に色空間を割り当てる従来の方法は、ICCプロファイルを画像内に埋め込むことです。データセットでクロールされたすべての画像に埋め込まれたすべてのICCプロファイルを調査しました。

以下がトップ10です:

| ICCプロファイルの説明 | sRGB系 | 広色域 | 画像の割合 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICCプロファイルなし | ✓ | 87.7% | |

| sRGB IEC61966-2.1 | ✓ | 3.8% | |

| c2ci | ✓ | 3.2% | |

| sRGB | ✓ | 1.6% | |

| uRGB | ✓ | 0.9% | |

| Adobe RGB (1998) | ✓ | 0.7% | |

| Display P3 | ✓ | 0.4% | |

| c2 | ✓ | 0.3% | |

| GIMP built-in sRGB | ✓ | 0.3% | |

| Display | 0.3% |

ウェブ上の画像の大部分は、正しいレンダリングのためにsRGBのデフォルトに依存しており、ICCプロファイルをまったく含んでいません。

最も一般的なICCプロファイルは、完全な公式のsRGBカラープロファイルです。このプロファイルは比較的重く、3 KBの重さがあります。したがって、トップ10のICCプロファイルの残りのほとんどは、Clinton Ingrahmの424バイトのc2ciのような「sRGB系」プロファイルで、最小限のオーバーヘッドで画像がsRGBを使用していることを明確に指定しています。

この10年間で、ハードウェアとソフトウェアはますますsRGBで可能な色の範囲(いわゆるsRGB色域)の外側にある色をキャプチャして表示できるようになっています。Adobe RGB (1998)とDisplay P3は、トップ10に唯一2つの「広色域」プロファイルです。Adobe RGB (1998)の使用率は2022年からわずかに減少しましたが、Display P3は増加し、広色域ICCプロファイルの採用は相対的に約10%増加しています。絶対的な意味では、広色域ICCプロファイルはまだ比較的まれです。ウェブ上の画像の80分の1、ICCプロファイルを持つ画像の10分の1に見つかりました。

ここで非常に重要な注意点は、私たちの分析ではICCプロファイルだけを調査できたということです。前述の通り、これらのプロファイルは比較的重いものです。AVIFのような最新の画像形式(そして最近近代化されたPNGのような形式)では、CICPと呼ばれる標準を使用して画像の色空間をはるかに効率的に示すことができます—これにより一般的な色空間をわずか4バイトで示すことができます。現代的なPNGエンコーダや価値のあるAVIFエンコーダは、広色域の色空間を示すためにICCの代わりにCICPを使用するのが道理にかなっています。

しかし、私たちの分析では、CICPを含む画像は「ICCプロファイルなし」に分類されています。したがって、ウェブ上の広色域の使用に関する私たちの計算は、総採用率の推定値ではなく、下限と見なすべきです。言い換えれば、ウェブ上の画像の少なくとも80分の1は広色域であることがわかりました。

エンコード

ここまでウェブの画像リソースがどのようにエンコードされているかを把握したところで、それらがウェブサイトにどのように埋め込まれているかについて見ていきましょう。

フォーマットの採用状況

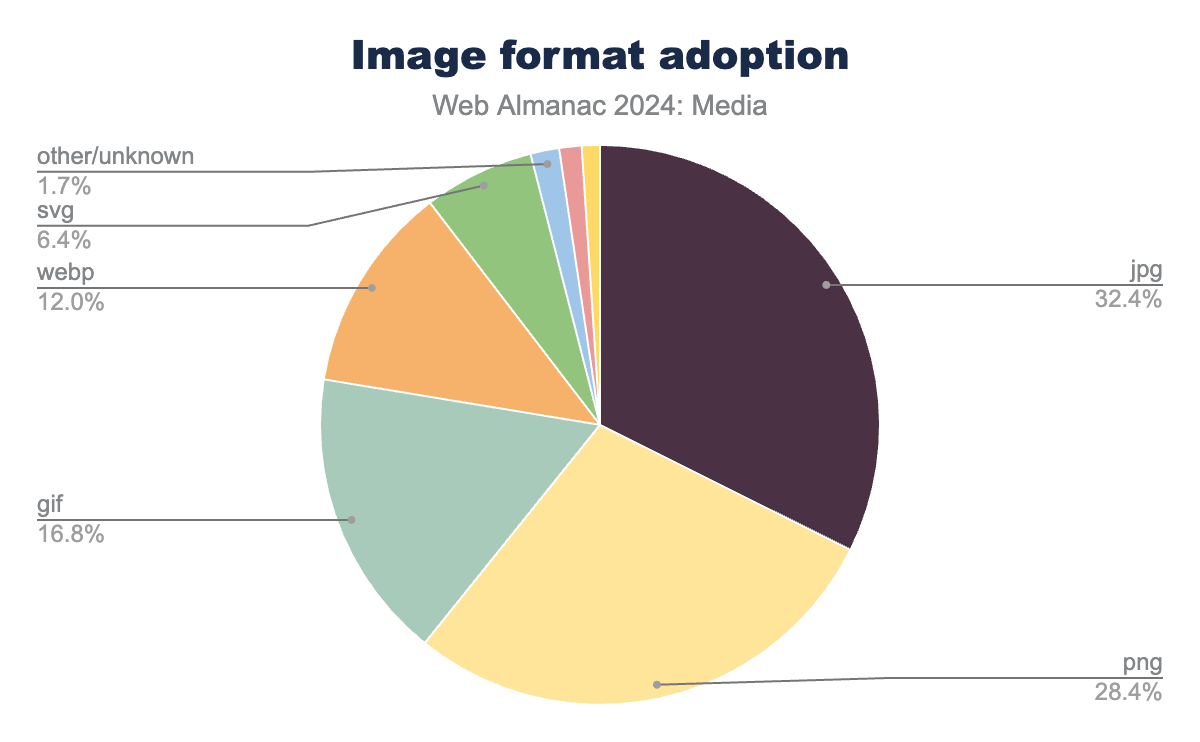

数十年間、ウェブ上で一般的に使用されていたビットマップフォーマットはJPG、PNG、GIFの3つだけでした。これらは今でも3つの最も一般的なフォーマットです:

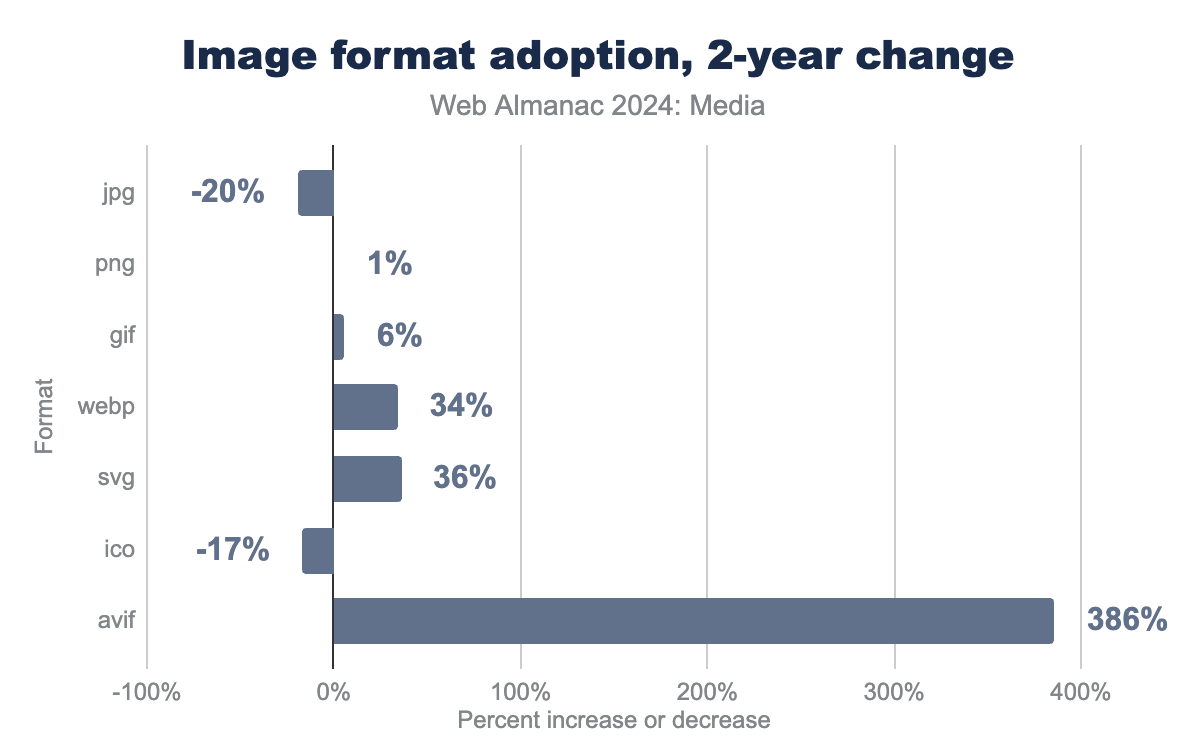

しかし、変化が起きていることを嬉しく報告できます。2022年以降の使用率における最大の絶対的変化はJPEGで、2022年のすべての画像の40%から8ポイント減少して2024年には32%になりました。これは2年間で大きな減少です。

その差を埋めるためにどのフォーマットがより多く使用されるようになったのでしょうか?WebPは3ポイント増加し、SVGは2ポイント弱増加し、AVIFはほぼ1ポイント増加しました。最も驚くべきことに、最も古く効率の悪いフォーマットであるGIFも1ポイント増加しました。

そして相対的な意味では、AVIFの使用は急増しています—2年前と比べて、クロールされたページで提供されるAVIFはほぼ4倍になりました。

クローラーがJPEG XLを受け入れていれば、おそらくかなりの数のJPEG XLも見られたでしょう。残念ながら、Chromiumベースのブラウザはこのフォーマットをサポートしていません。

ウェブ上のJPEG、PNG、GIFのほとんどすべては、最新のフォーマットを使用したほうが良いでしょう。WebPは良いですが、AVIFとJPEG XLはさらに優れています。ウェブ上のすべての画像という巨大な船が、これらのより効率的なフォーマットへとゆっくりではあるが確実に方向転換していくのは良いことです。またSVGの使用率が上昇していることも良いことです!

最後に、最も古いフォーマットについて少し言及しておきましょう:「すべてのGIFを燃やせ」は1999年に良いアドバイスでしたが、今日ではさらに良いアドバイスです。開発者はこの37年前のフォーマットを置き換える方法についてTyler Stickaのアドバイスに従うべきです。

バイトサイズ

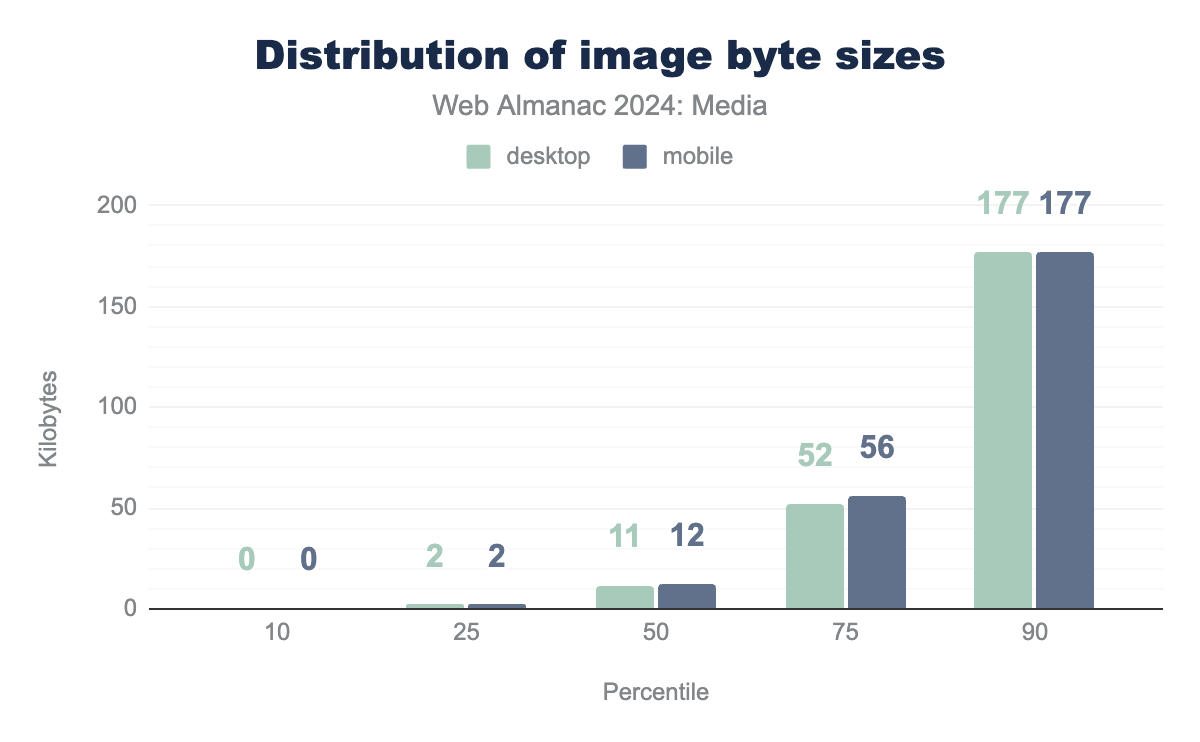

ウェブ上の典型的な画像はどれくらい重いのでしょうか?

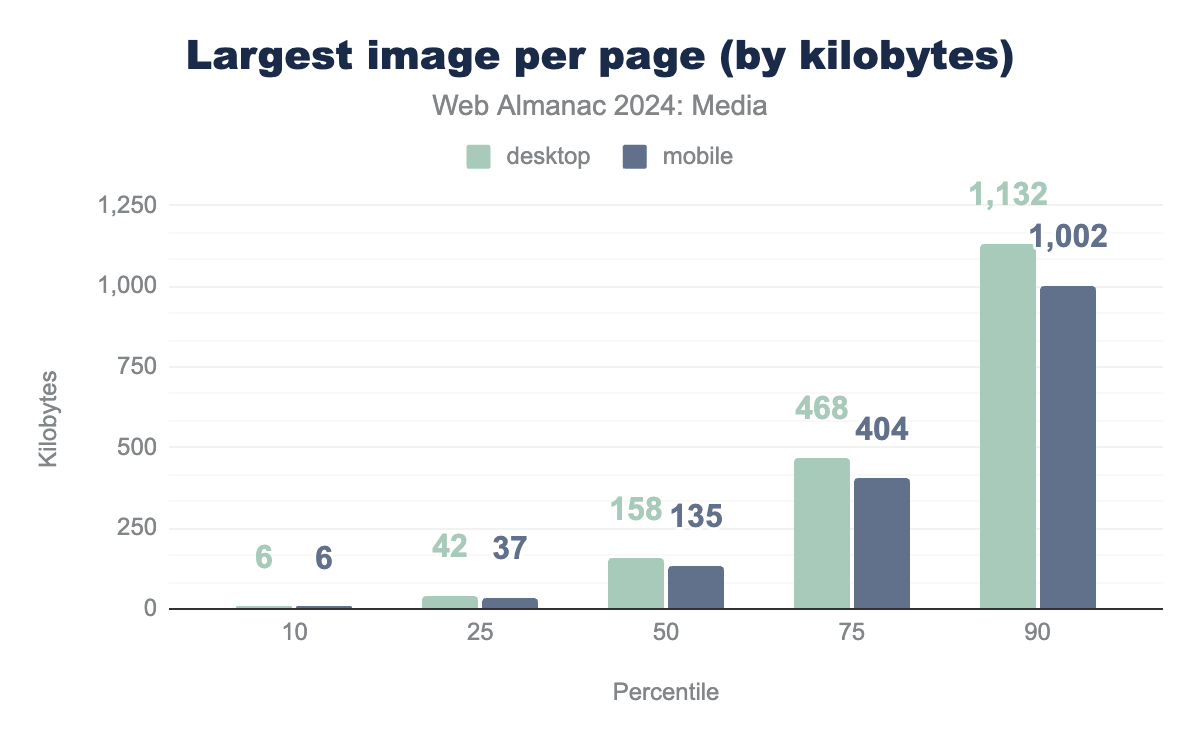

中央値の12 KBは「そんなに重くないじゃないか!」と思わせるかもしれません。しかし、ピクセル数を見たときと同様に、ほとんどのページには多くの小さな画像と、少なくとも1つの大きな画像が含まれていることがわかりました。

ほとんどのモバイルページには、135 KB以上の画像が1つあります。これは2022年以降8%の増加です。そして分布の上位に行くほど、加速しています:75パーセンタイルは10%増加し、90パーセンタイルは13%増加(ほぼ正確に1メガバイト)しています。

画像はより重くなり、最も重い画像はより速く重くなっています。

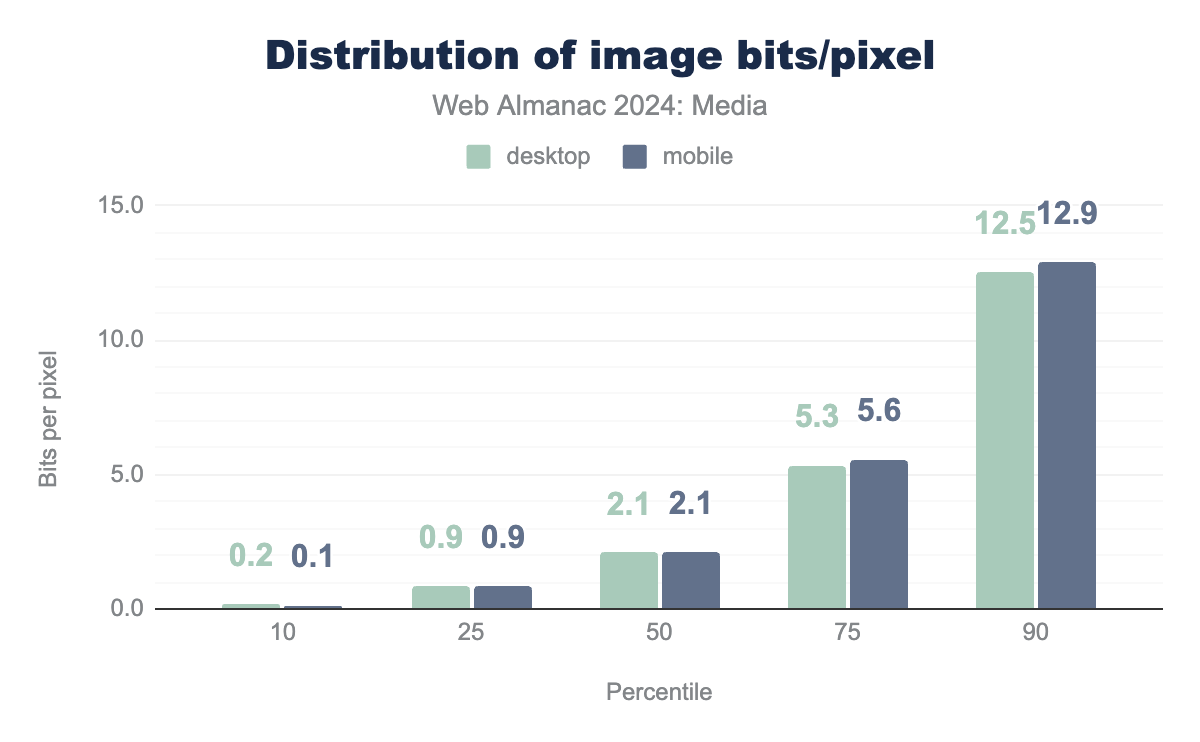

ピクセルあたりのビット数

バイト数とピクセル数はそれ自体で興味深いですが、ウェブ上の画像データがどれだけ圧縮されているかを知るためには、バイト数とピクセル数を組み合わせてピクセルあたりのビット数を計算する必要があります。これにより、画像の解像度が異なる場合でも、画像の情報密度を同等に比較することができます。

一般的に、ウェブ上のビットマップは、チャネルごと(ピクセルごと)に8ビットの非圧縮情報としてデコードされます。したがって、透明度のないRGB画像がある場合、デコードされた非圧縮画像はピクセルあたり24ビットの重さになると予想できます。

可逆圧縮に関する良い経験則は、ファイルサイズが2:1の比率で縮小されるべきということです(8ビットのRGB画像の場合、ピクセルあたり12ビットになります)。1990年代の非可逆圧縮方式(JPEGやMP3)の経験則は10:1の比率(ピクセルあたり2.4ビット)でした。

画像の内容とエンコード設定に応じて、これらの比率は大きく異なり、MozJPEGやJpegliのような最新のJPEGエンコーダは、デフォルト設定でこの10:1の目標を上回ることが多いことに注意すべきです。

要約すると:

| ビットマップデータの種類 | 予想される圧縮率 | ピクセルあたりのビット数 |

|---|---|---|

| 非圧縮RGB | 1:1 | 24ビット/ピクセル |

| 可逆圧縮RGB | ~2:1 | 12ビット/ピクセル |

| 1990年代の非可逆RGB | ~10:1 | 2.4ビット/ピクセル |

そこで、これらすべてを背景として、ウェブ上の画像はどのようになっているでしょうか:

中央値の画像はピクセルあたり2.1ビットに圧縮されており、これは1990年代の経験則よりも少し多い圧縮を表しています。これはまた、2022年に最後にウェブの画像を調査したときに見た圧縮率よりも8〜10%多い圧縮です。

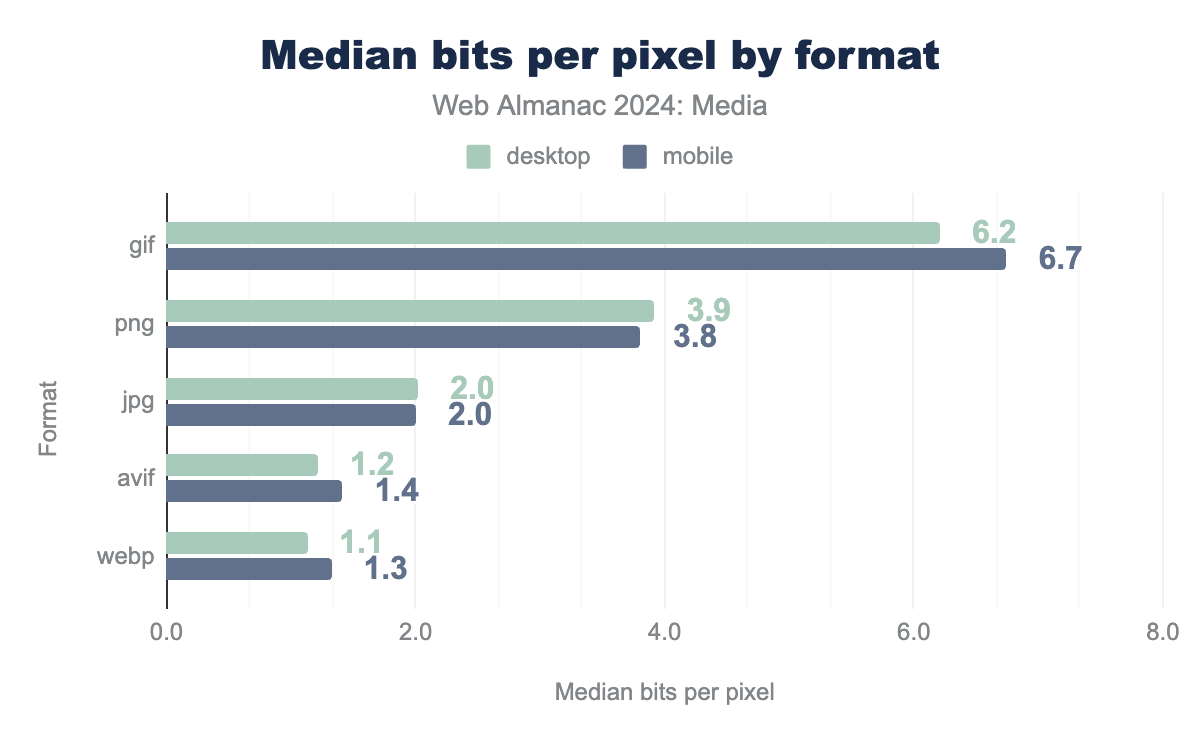

圧縮をフォーマット別に分類すると、2022年と比較して2024年はすべてのフォーマットでピクセルあたりに費やされるビットが少なくなっていることが分かります—1つを除いて。

フォーマット別のピクセルあたりビット数

2022年と比較して、モバイルでは、中央値のPNGは約10%多く圧縮され、中央値のWebPは約7%多く圧縮され、中央値のJPEGは約3%多く圧縮されています。ここでの原因を正確に知ることは難しいですが、私たちは圧縮の増加は2つのことのより広い採用の結果であると仮説しています:より多くの価値を提供する最新のエンコーダと、すべての画像がユーザーに届く前に適切に圧縮されていることを確認する自動画像処理パイプラインです。

この傾向に逆らった1つのフォーマットはAVIFでした。中央値のAVIFのピクセルあたりビット数は、2022年の約1.0から2024年には約1.4ビット/ピクセルに増加しました—これは47%の増加です。面白いことに、私たちは同じ根本原因を仮説としています。現在の多様なAVIFエンコーダは、2年前のAOMの公式libavifエンコーダよりもデフォルト設定で品質を犠牲にすることが少ない、異なる品質/ファイルサイズのトレードオフを行っている可能性が高いです。

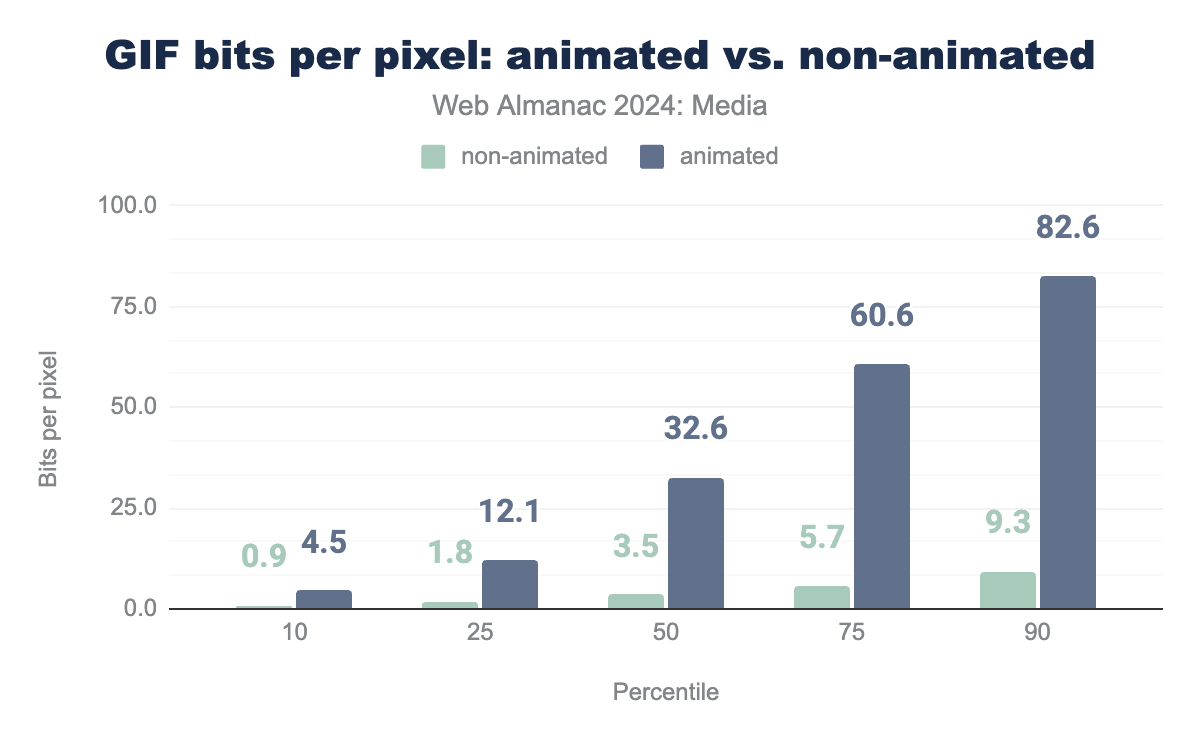

GIFがなぜ大幅に効率的になったのかはわかりませんが、なぜGIFが他のすべてのフォーマットよりもはるかに圧縮率が低いのかはわかります。私たちのクエリはピクセルごとであり、多くのGIFがアニメーションであるにもかかわらず、アニメーション画像を考慮していません!

GIF、アニメーションとそうでないもの

どれだけのGIFがアニメーションなのでしょうか?

アニメーションGIFとアニメーションではないGIFを分けてみると、アニメーションではない中央値のGIFははるかに合理的に圧縮されていることがわかります:

3.5ビット/ピクセルは中央値のPNGよりも少ないです!

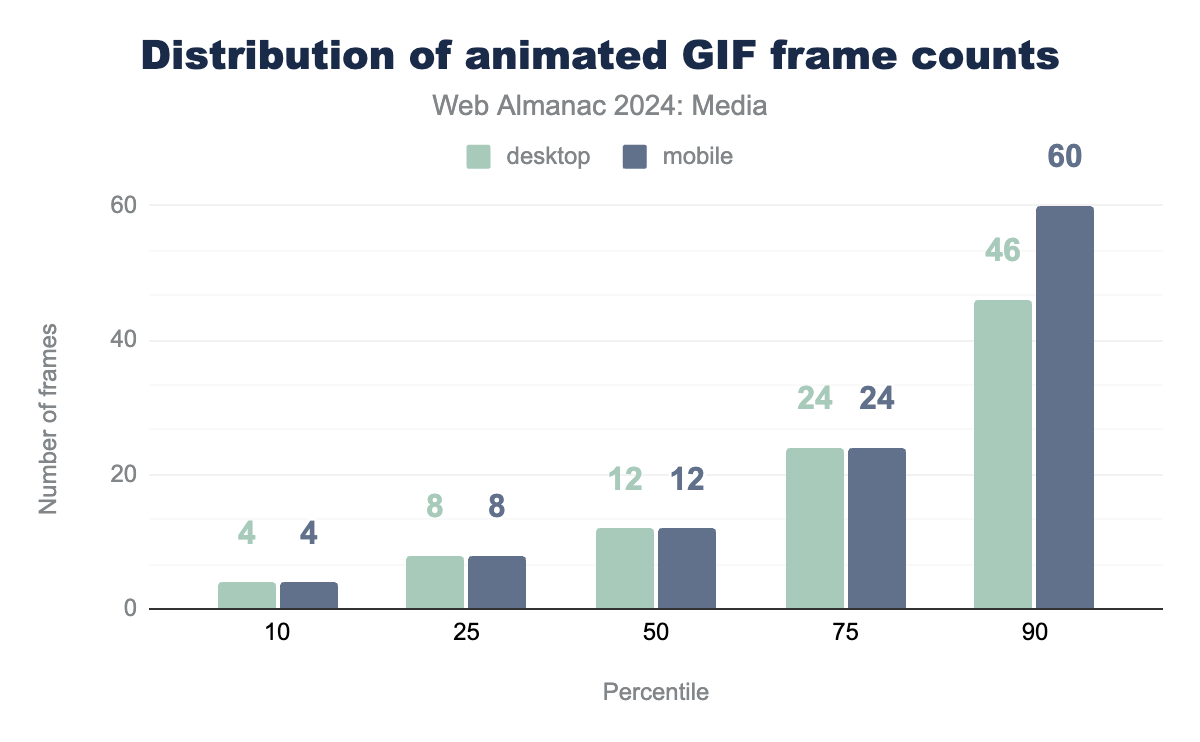

特にアニメーションGIFに目を向けると:それらはどれくらいのフレーム数を持っているのでしょうか?

一般的には:10〜20フレームで、これは2022年からほとんど変わっていませんが、最も長いGIFは特にモバイルでより長くなっています。

参考までに、最も多くのフレーム数を持つGIFも調査しました:

24フレーム/秒では、一通り再生するのに37分以上かかります。すべてのアニメーションGIFはおそらく現在では動画であるべきですが、これは間違いなくそうあるべきです。

埋め込み

ウェブの画像リソースがどのようにエンコードされているかを理解したところで、それらがウェブサイトにどのように埋め込まれているかについて何が言えるでしょうか?

遅延読み込み

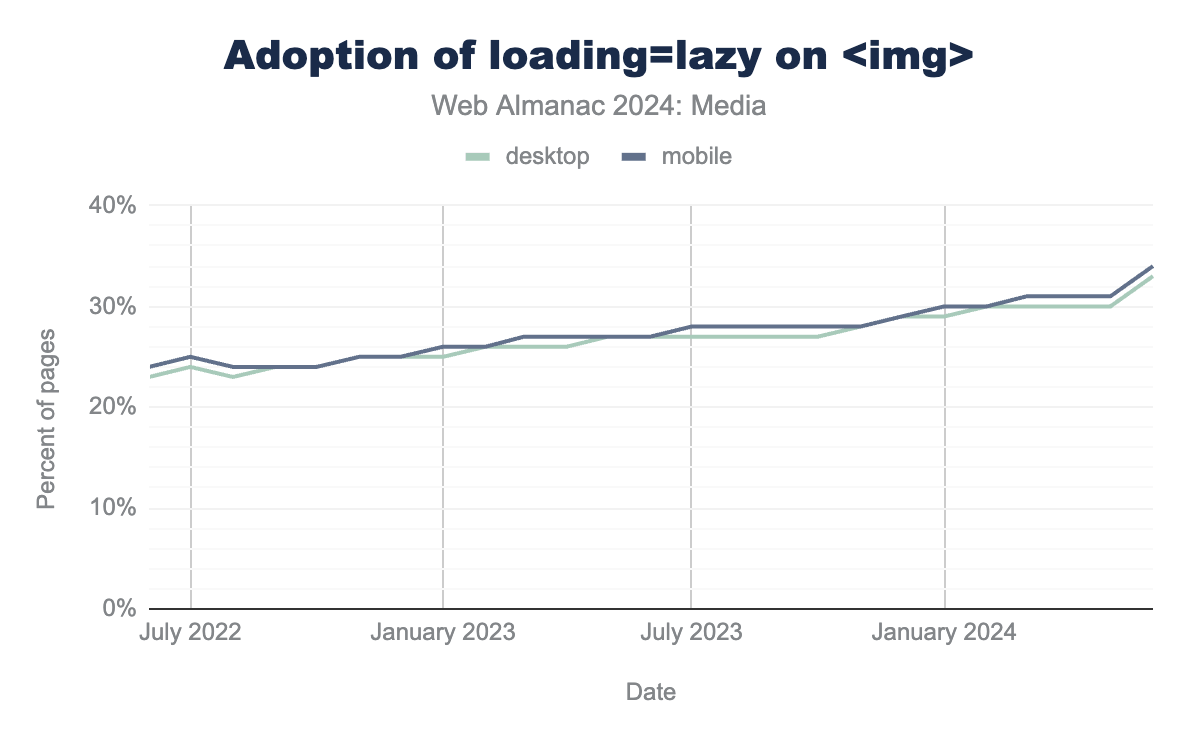

ウェブサイトに画像が埋め込まれる方法における最近の最大の変化は、遅延読み込みの急速な採用でした。遅延読み込みは2020年に導入され、わずか2年後にはほぼ4分の1のウェブサイトで採用されました。その上昇は続き、現在ではすべてのウェブサイトの完全に3分の1で使用されています:

<img loading=lazy>)の採用状況。

そして、昨年と同様に、遅延読み込みを少し使いすぎているようです:

<img>要素の割合。

LCP要素を遅延読み込みすることは、ページを大幅に遅くするアンチパターンです。LCP対象の<img>の10個に1個近くが遅延読み込みされていることは落胆させられますが、過去2年間でわずかに改善されていることを報告できることは嬉しいことです。違反サイトの割合は2022年から0.3パーセントポイント減少しています。

alt テキスト

<img>要素で埋め込まれる画像は、内容を持つべきものです。つまり、単なる装飾ではなく、意味のあるものを含むべきです。WCAG要件とHTML仕様の両方によれば、ほとんどの場合、<img>要素には代替テキストが必要であり、その代替テキストはalt属性によって提供されるべきです。

alt属性を持つ画像の割合。

残念ながら、<img>要素の45パーセントにはaltテキストがありません。さらに悪いことに、今年のアクセシビリティの章からの詳細な分析によると、altテキストを持つ<img>の多くも、その属性にはファイル名や他の意味のない短い文字列しか含まれていないため、それほどアクセシブルではありません。

2022年以降、altテキストの導入は1パーセントポイント増加していますが、私たちはさらに—そしてそうしなければなりません—改善できます。

srcset

遅延読み込みの前に、ウェブ上の<img>要素に起きた最大の変化は、「レスポンシブイメージ」のための機能セットで、これによって画像がレスポンシブデザイン内に適合するように調整できるようになりました。2014年に最初にリリースされたsrcset属性、sizes属性、<picture>要素は現在10年の歴史を持っています。私たちはこれらをどれくらいの頻度で、どれくらい上手に使用しているでしょうか?

まず、srcset属性から見ていきましょう。これによって作成者は、コンテキストに応じてブラウザに選択肢となるリソースのメニューを提供できます。

srcset属性を使用しているページの割合。

前回確認した時、この数字は34%でした—2年間で8パーセントポイントの増加は重要であり、勇気づけられます。

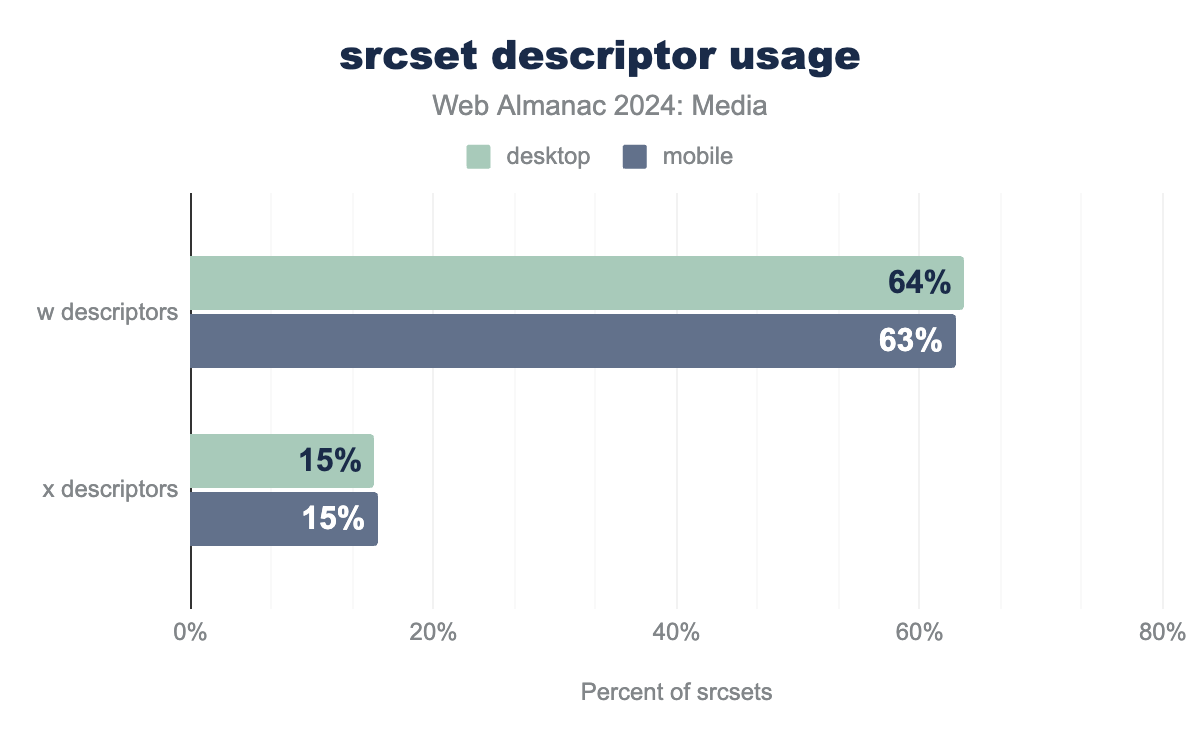

srcset属性により、作成者は2つの記述子のいずれかを使用してリソースを記述できます。x記述子はリソースの密度を指定し、ブラウザがユーザーの画面密度に応じて異なるリソースを選択できるようにします。w記述子はブラウザにリソースの幅をピクセル単位で提供します。sizes属性と組み合わせて使用すると、w記述子によりブラウザは可変レイアウト幅と可変画面密度の両方に適したリソースを選択できます。

x記述子とw記述子を使用しているsrcsetの割合を示す棒グラフで、モバイルとデスクトップの両方を示しています。x記述子はデスクトップとモバイルの両方でsrcsetの15%で使用されています。w記述子は4倍多く使用されており、デスクトップでは64%、モバイルでは62%の頻度で使用されています。srcset記述子の使用状況。

x記述子が最初に出荷され、理解しやすいものですが、w記述子はより強力です。w記述子がより一般的であることを見るのは勇気づけられます。そして、x記述子の採用は2022年からほとんど増加していませんが、w記述子の使用はまだ成長し続けています—w記述子の採用はモバイルで4パーセントポイント、デスクトップで6パーセントポイント増加しています。

sizes

先ほど、w記述子はsizes属性と組み合わせて使用すべきだと述べました。では、私たちはsizesをどれくらい上手に使用しているでしょうか?あまり上手ではありません!

sizes属性は、画像の最終的なレイアウト幅についてブラウザへのヒントとなるもので、通常はビューポート幅に対する相対値です。sizes属性は明示的にヒントであることが意図されているため、多少の不正確さは問題なく、むしろ予想されています。

しかし、sizes属性が少し以上に不正確である場合、リソース選択に影響を与える可能性があり、実際の画像のレイアウト幅が大きく異なる場合でも、ブラウザがsizes幅に合わせて画像を読み込む原因となります。

では、私たちのsizesはどれくらい正確でしょうか?

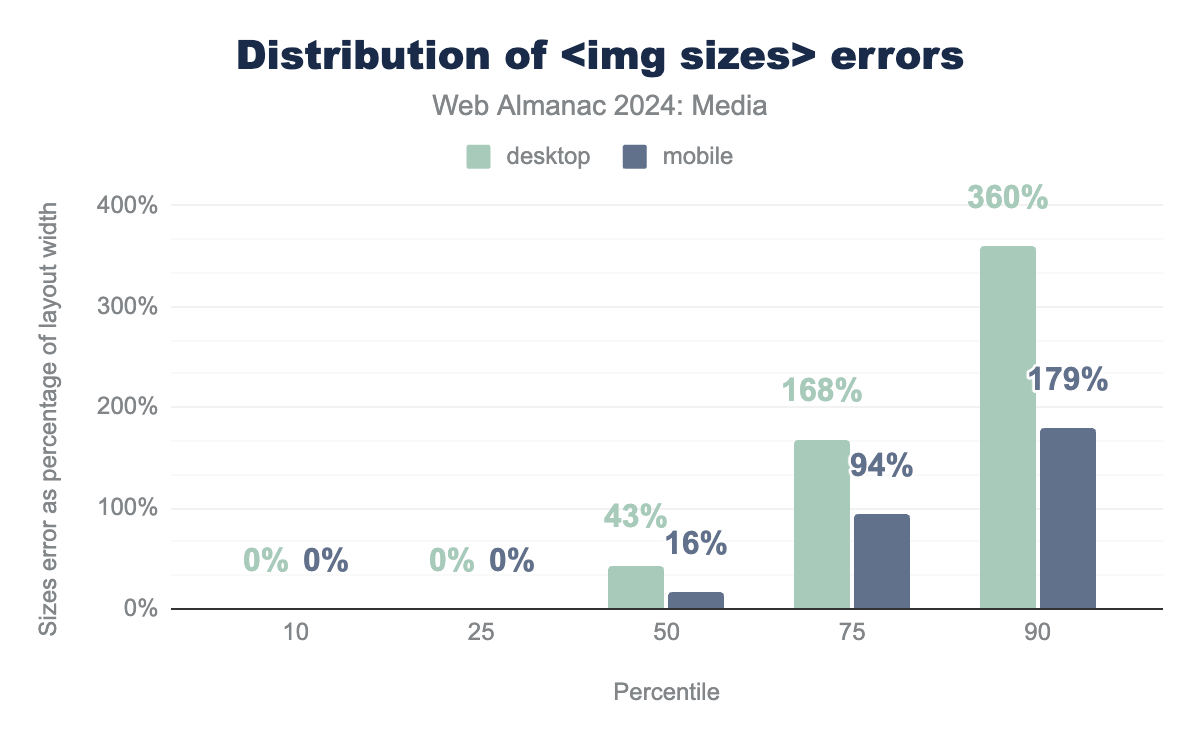

sizes属性の相対的なエラーの分布を示す棒グラフ。最初はすべてゼロで、10パーセンタイルと25パーセンタイルではデスクトップとモバイルの両方で0%です。50パーセンタイルではデスクトップで43%、モバイルで16%、75パーセンタイルではそれぞれ168%と94%、そして90パーセンタイルではデスクトップで360%、モバイルで179%となっています。<img sizes>エラーの分布。

多くのsizes属性は完全に正確ですが、中央値のsizes属性はモバイルで16%、デスクトップで43%大きすぎます。この機能のヒント的な性質を考えると問題ないかもしれませんが、ご覧のように、75パーセンタイルと90パーセンタイルはかなり悪い状況です。最も懸念されるのは、これらの数値がすべて過去2年間で大幅に悪化していることで、デスクトップの中央値のsizesは2年前よりも2倍以上不正確になっています。

こうした不正確さの影響はどれほどでしょうか?

srcset選択に影響を与えるほど不正確だったsizes属性の割合。モバイルでは14%です。

デスクトップでは、デフォルトのsizes値(100vw)と画像の実際のレイアウト幅の差がモバイルよりも大きくなる可能性が高く、5つに1つのsizes属性が不正確すぎて、ブラウザがsrcsetから最適ではないリソースを選択する原因となっています。これらのエラーは積み重なります。

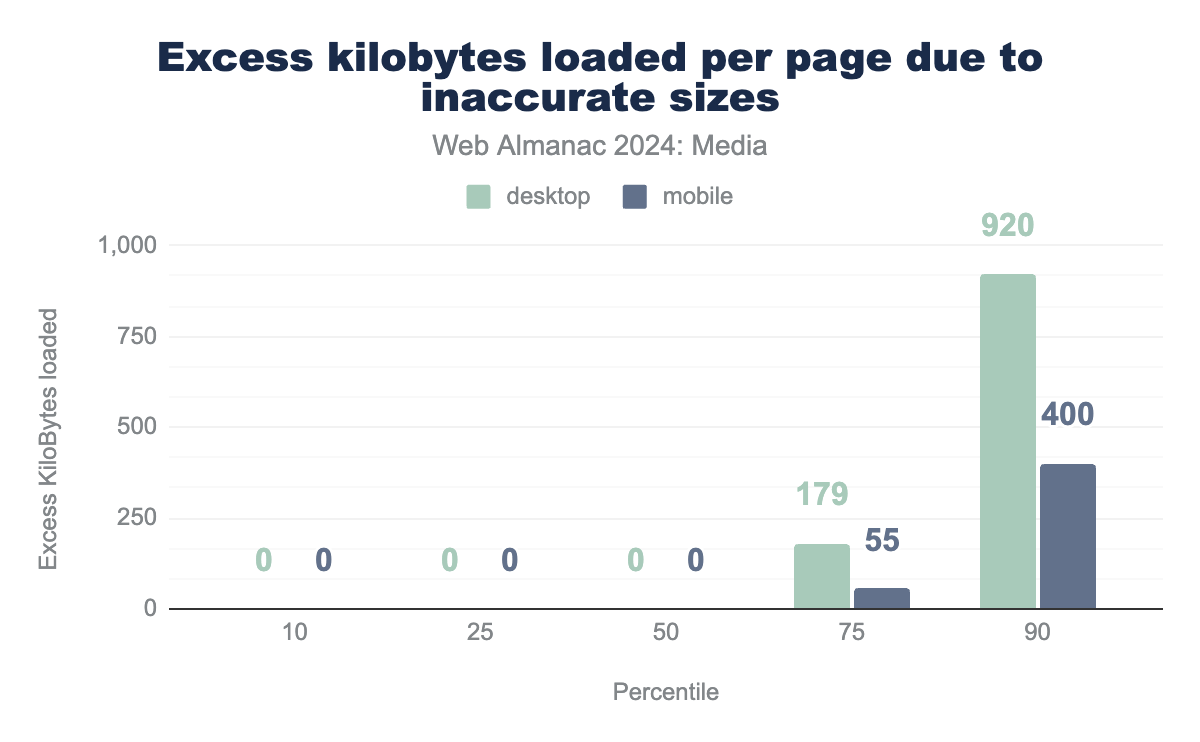

sizes属性によってページごとに無駄に読み込まれるキロバイトの分布を示す棒グラフ。最初はゼロばかりです。10パーセンタイル、25パーセンタイル、50パーセンタイルでは、モバイルとデスクトップの両方でゼロキロバイトです。75パーセンタイルでは、デスクトップクローラーは179キロバイト、モバイルでは55キロバイトの無駄を検出し、90パーセンタイルでは、デスクトップでは920キロバイト、モバイルでは400キロバイトでした。sizesによってページごとに読み込まれる余分なキロバイト。

私たちの推定では、w記述子を使用するデスクトップページの4分の1が、不正確なsizes属性のために180KB以上の無駄な画像データを読み込んでいます。つまり、srcsetにはより良い、より小さなリソースがあるにもかかわらず、sizes属性が非常に誤っているため、ブラウザはそれを選択しません。w記述子を使用するデスクトップページの最も悪い10%は、不良なsizes属性のために約1メガバイトの余分な画像データを読み込んでいます。

これはかなり問題ですが、さらに悪いことに、これらの数字はすべて、わずか2年前と比較して約2倍悪化しています。状況は悪く、さらに悪化しています。

開発者が追求すべき2つの解決策があります。

LCP対象および他の重要な画像については、開発者はsizes属性を修正する必要があります。sizesを監査および修正するための最良のツールはRespImageLintで、これは他の多くのレスポンシブ画像の問題も修正するのに役立ちます。

ビューポート外(below-the-fold)や重要でない画像については、作成者はsizes="auto"を採用し始めるべきです。この値は遅延読み込みと組み合わせてのみ使用できますが、ブラウザに<img>の実際のレイアウトサイズをsizes値として使用するよう指示し、使用される値が完全に正確であることを保証します。

遅延読み込み画像の自動sizesは現在Chromeでのみ実装されていますが、SafariとFirefoxの両方がそれをサポートする意向を表明しています。彼らがすぐにそれを実装し、開発者が(フォールバック値を伴って)今すぐそれを展開し始めることを期待しています。

<picture>

2014年に最後に登場したレスポンシブイメージ機能は<picture>要素でした。srcsetがブラウザに選択肢となるリソースのメニューを提供するのに対し、<picture>要素は作者が主導権を握り、どの子<source>要素からリソースを読み込むかについての明示的なコンテキスト適応型の指示をブラウザに与えることができます。

<picture>要素はsrcsetよりもはるかに少なく使用されています:

<picture>要素を使用しているモバイルページの割合。

この数字は2022年から1.5パーセントポイント以上増加していますが、<picture>を使用する1ページに対してsrcsetを使用するページが4ページ以上あるという事実は、<picture>のユースケースがより限定的であるか、<picture>の導入がより困難であるか、あるいはその両方であることを示唆しています。

人々は<picture>をどのような目的で使用しているのでしょうか?

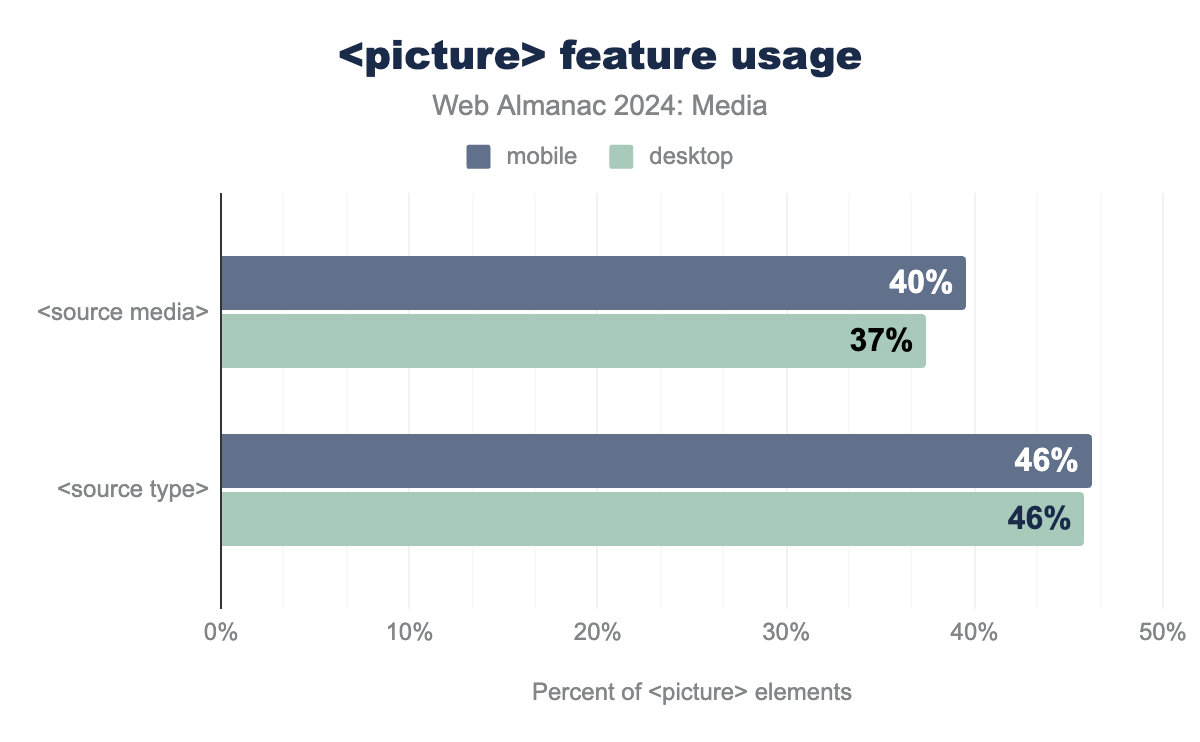

<picture>要素は、作者にリソースを切り替える2つの方法を提供します。タイプ切り替えにより、作者は最先端の画像フォーマットをサポートするブラウザに提供し、他のすべてのブラウザにはフォールバックフォーマットを提供することができます。メディア切り替えはアートディレクションを容易にし、作者がメディア条件に基づいて<source>間を切り替えることを可能にします。

picture要素と組み合わせて、source要素上でmedia属性とtype属性を使用しているページの割合を示す棒グラフ。mediaはモバイルではpicture要素の40%、デスクトップでは37%で使用されています。typeはモバイルとデスクトップの両方でpicture要素の46%で使用されています(ただし、モバイルの棒グラフはわずかに大きくなっています)。<picture>機能の使用状況。

2022年からmedia属性の使用は3パーセントポイント減少していますが、type切り替えの使用は3パーセントポイント増加しています。この増加は、次世代画像フォーマット、特にまだ普遍的なブラウザサポートを享受していないJPEG XLの人気の高まりと関連している可能性が高いです。

レイアウト

私たちはすでにウェブの画像リソースがどのようなサイズであるかを見てきました。しかし、ユーザーに表示される前に、埋め込まれた画像はレイアウト内に配置され、場合によっては押しつぶされたり引き伸ばされたりして適合させる必要があります。

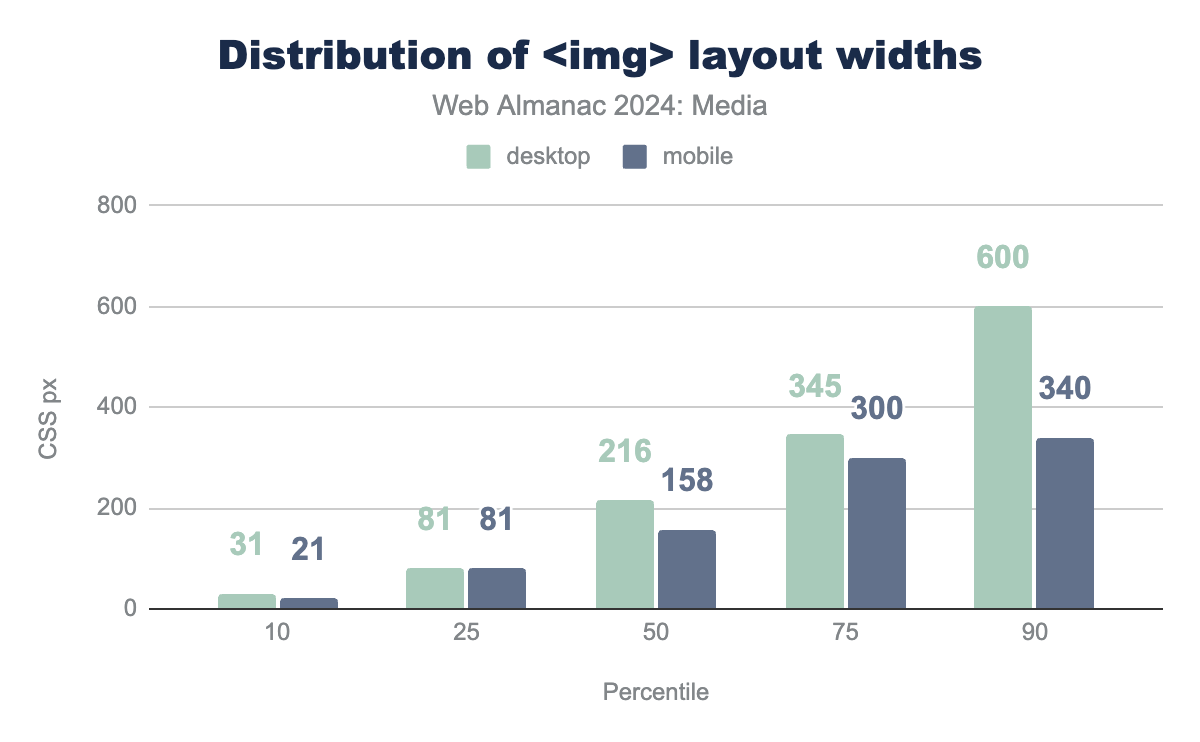

レイアウト幅

まず次の質問から始めましょう:ウェブの画像はページに描画されるとどれくらいの幅になるのでしょうか?

<img>レイアウト幅の分布。

ウェブ上のほとんどの画像はレイアウト内ではかなり小さくなっています。興味深いことに、モバイルのレイアウトサイズの大部分は2022年からほとんど変わっていませんが、デスクトップのレイアウトサイズの上位半分はすべて約8%増加しています。

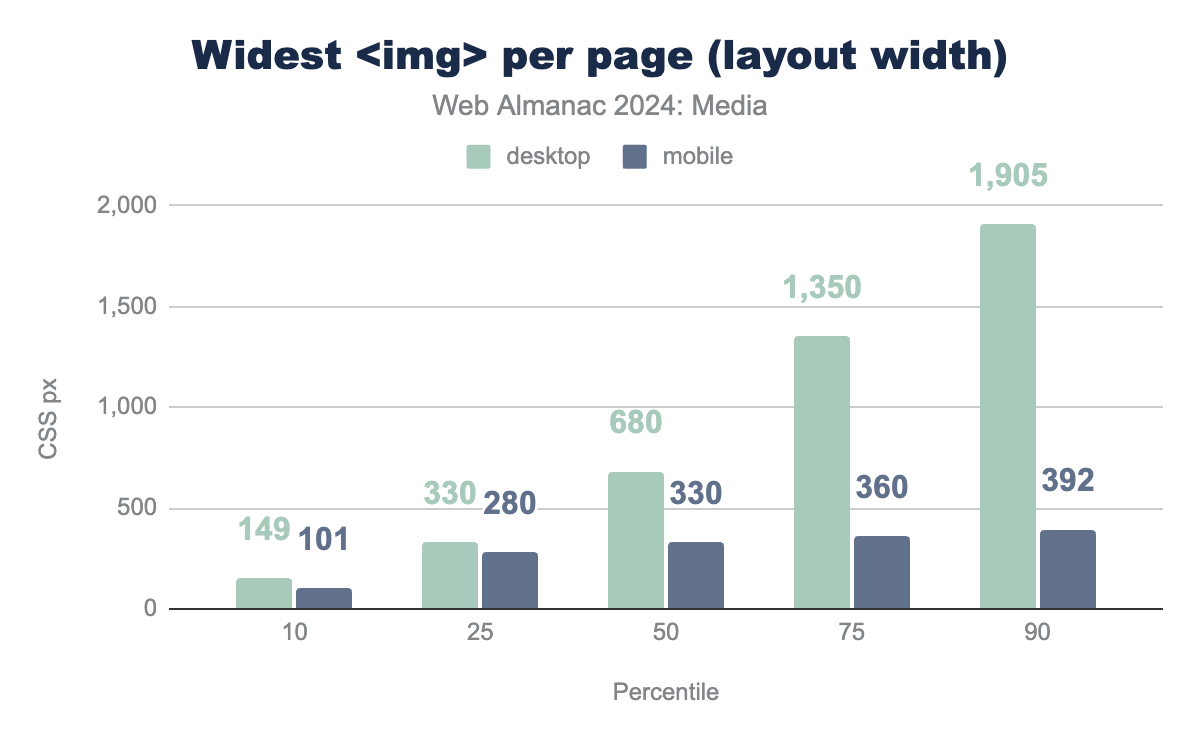

しかし、レイアウトサイズの大多数が小さい一方で、ほとんどのページには少なくとも1つのかなり大きな<img>があります。

<img>(レイアウト幅別)。

すべてのモバイルページの半分には、ビューポートのほぼ全体を占める画像が少なくとも1つあります。上位の方では、モバイルレイアウトは画像がそれ以上のスペースを占めないようにうまく抑制しています。分布がモバイルクローラーのビューポート幅(360px)にすぐに近づき、それをわずかに超えるだけであることがわかります。

これに対してデスクトップのレイアウト幅は、まったく頭打ちになっていません。それらは拡大し続け、75パーセンタイルでフルビューポート幅(1360px)に達し、90パーセンタイルではそれを大きく超えています。同様に興味深いのは、デスクトップでの25、50、75パーセンタイルのレイアウトサイズが2年前よりも大きくなっている一方で、分布の端はほとんど変わっていないことです。大きなヒーロー画像はさらに大きくなっています。

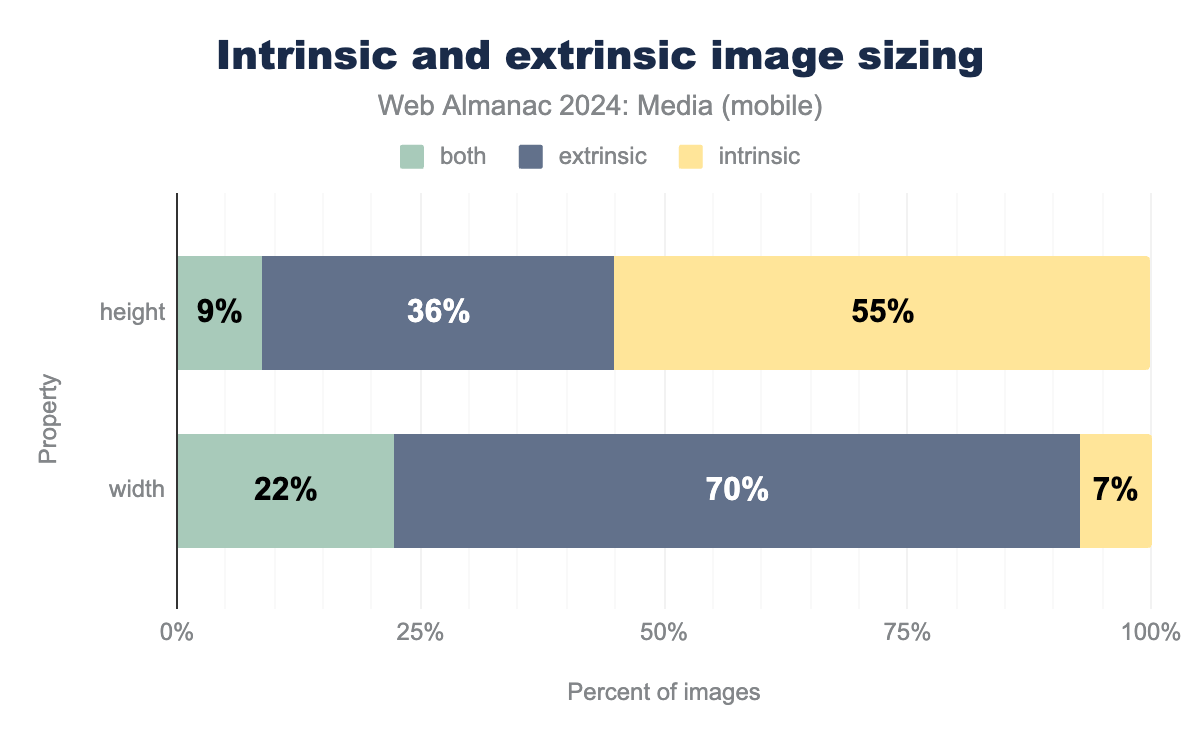

内在的 vs 外在的サイジング

ウェブの画像はどのようにしてこれらのレイアウトサイズになるのでしょうか?CSSで画像をスケーリングする方法はたくさんありますが、実際にCSSでスケーリングされている画像はどれくらいあるのでしょうか?

画像は、すべての“置換要素”と同様に、内在的サイズを持っています。デフォルトでは—密度を制御するsrcsetやレイアウト幅を制御するCSSルールがない場合—ウェブ上の画像は1xの密度で表示されます。640×480の画像を<img src>に配置すると、デフォルトではその<img>は幅640 CSSピクセルでレイアウトされます。

作者は画像の高さ、幅、またはその両方に外在的サイジングを適用することができます。画像が一方の次元で外在的にサイズ設定されている場合(例えば、width: 100%;ルールによる)、しかしもう一方の次元では内在的サイズのままである場合(height: auto;または何もルールがない)、内在的なアスペクト比を使用して比例的にスケーリングされます。

さらに複雑なことに、いくつかのCSSルールは、内在的な次元が何らかの制約に違反しない限り、<img>要素を内在的な次元に基づいてサイズ設定します。例えば、max-width: 100%;ルールを持つ<img>要素は、内在的サイズが<img>要素のコンテナのサイズよりも大きい場合を除いて、内在的にサイズ設定されます。その場合は、外在的に縮小されて適合します。

これらの説明を踏まえて、ウェブの<img>要素がレイアウトのためにどのようにサイズ設定されているかを見てみましょう:

大多数の画像は外在的な幅と内在的な高さを持っています。幅の「両方」カテゴリ—max-widthまたはmin-widthのサイジング制約を持つ画像を表す—もかなり人気があります。画像を内在的な幅のままにしておくことははるかに人気が低く、2022年よりもわずかに人気が低くなっています。

height, width属性と累積レイアウトシフト

内在的な寸法に依存するレイアウトサイズを持つ<img>は、累積レイアウトシフト(CLS)を引き起こすリスクがあります。本質的に、そのような画像はレイアウトが2回行われるリスクがあります—1回目はページのDOMとCSSが処理された時点で、そして2回目は最終的に読み込みが完了し、内在的な寸法が判明した時点です。

先ほど見たように、特定の幅に合わせて画像を外在的にスケーリングしながら、高さ(およびアスペクト比)を内在的なままにしておくことは非常に一般的です。このようなレイアウトシフトの蔓延を防ぐために、作者は<img>要素にwidthとheight属性を設定すべきです。これによりブラウザは埋め込みリソースが読み込まれる前にレイアウトスペースを確保できます。

heightとwidth属性の両方が設定されている<img>要素の割合。

heightとwidthの使用は2022年から4パーセントポイント増加しており、これは良いことです。しかし、これらの属性はまだ画像の3分の1にしか使用されておらず、まだ長い道のりがあることを意味しています。

配信

最後に、画像がネットワーク上でどのように配信されているかを見てみましょう。

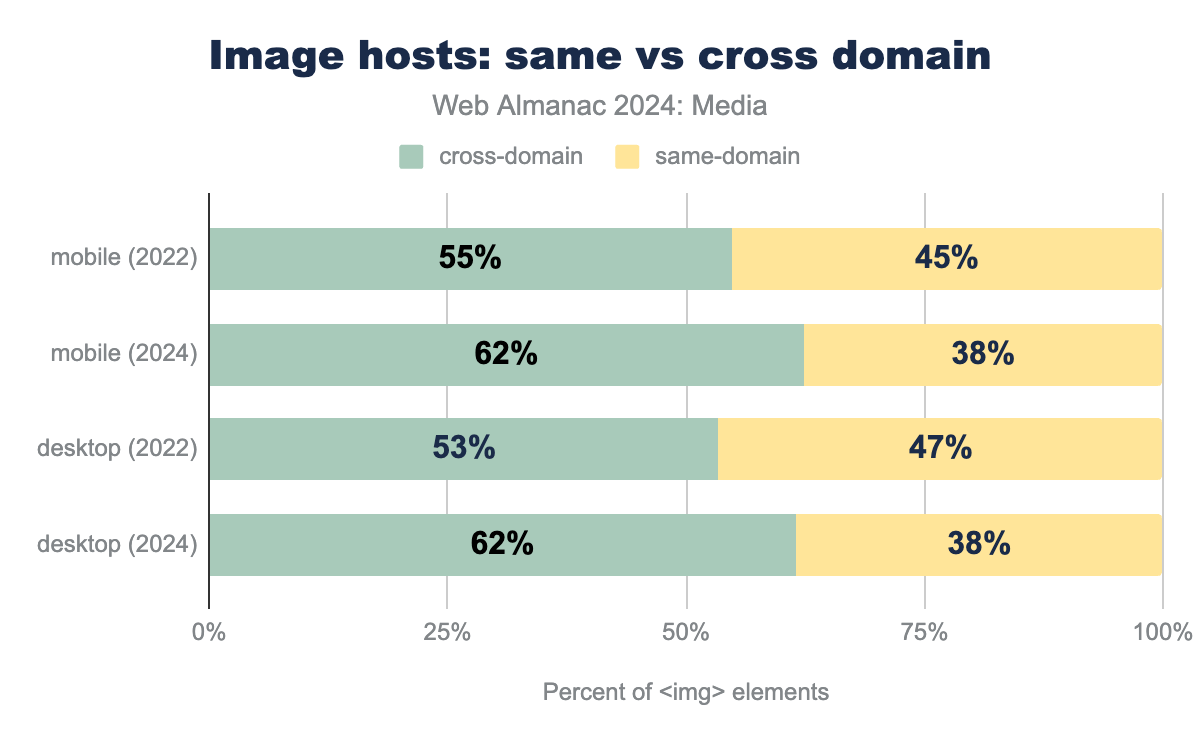

クロスドメイン画像ホスト

埋め込まれた文書とは異なるドメインから配信されている画像はどれくらいあるのでしょうか?増加する多数派です:

ここでのさまざまな潜在的な原因を解きほぐすのは難しいですが、私たちは画像を正しく扱うことがいかに難しいかが一つの要因であるという仮説を立てています。これによりチームは画像CDNを採用するようになり、画像の最適化と配信をサービスとして提供しています。

これで、ウェブ上の画像の現状についての全体像が得られました。次に、2024年のウェブ上の動画について見ていきましょう。

動画

<video>要素は2010年に登場し、それ以来、FlashやSilverlightなどのプラグインが廃止されて以来、ウェブサイトに動画コンテンツを埋め込むための最良かつ唯一の方法となっています。私たちはそれをどのように使用しているでしょうか?

<video>要素の採用

まず最初に、最も基本的な質問に答えましょう:どれくらいのページが<video>要素を含んでいるのでしょうか?

<video>要素を含むモバイルページの割合。デスクトップでは7.7%です。

これは<img>を含むページの数に比べると小さな割合です。しかし、<video>が14年前に導入されたにもかかわらず、現在採用は急速に増加しています。モバイルの数字は2022年から(相対的に)32%増加しています。

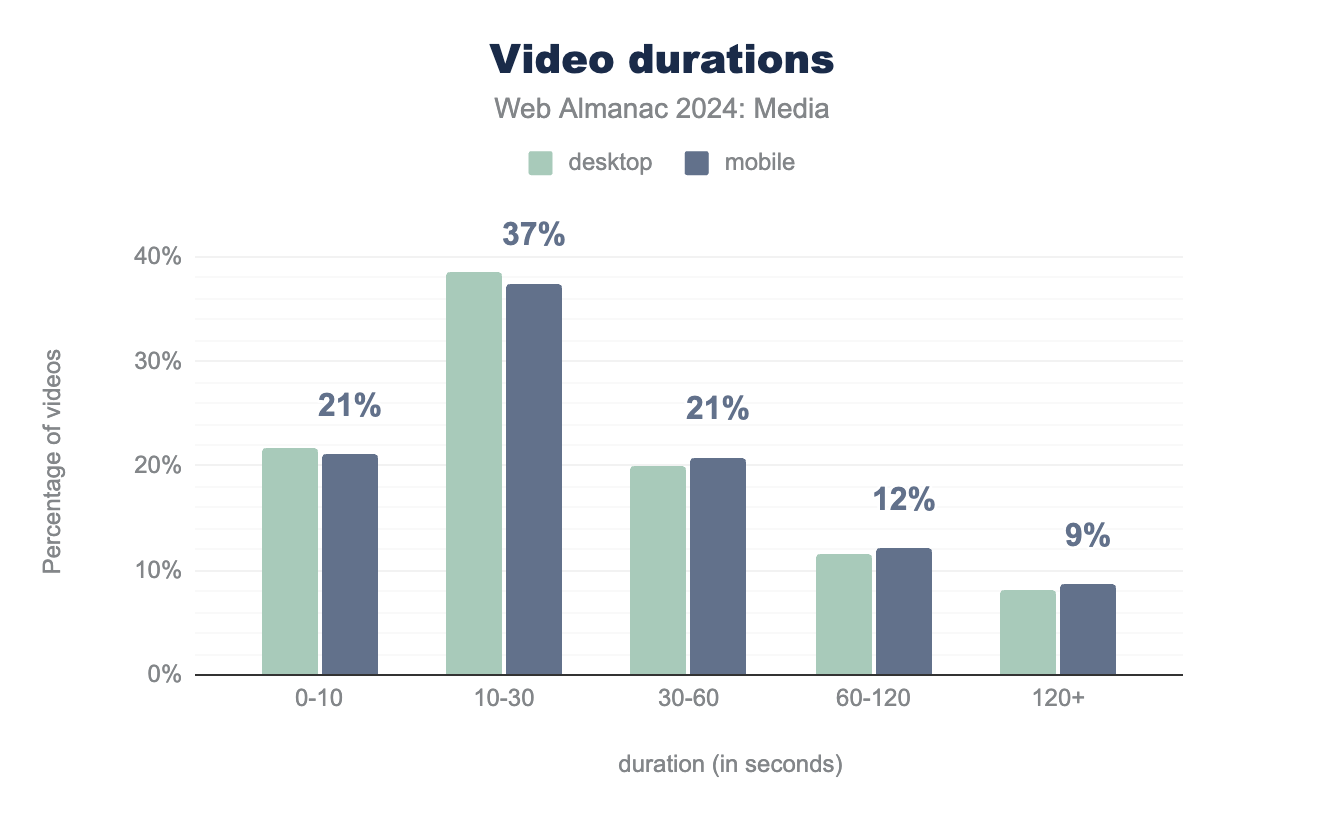

動画の長さ

これらの動画はどれくらいの長さなのでしょうか?そんなに長くありません!

10本中9本の動画は2分未満です。半分以上が30秒未満です。そして、動画のほぼ4分の1が10秒未満です。

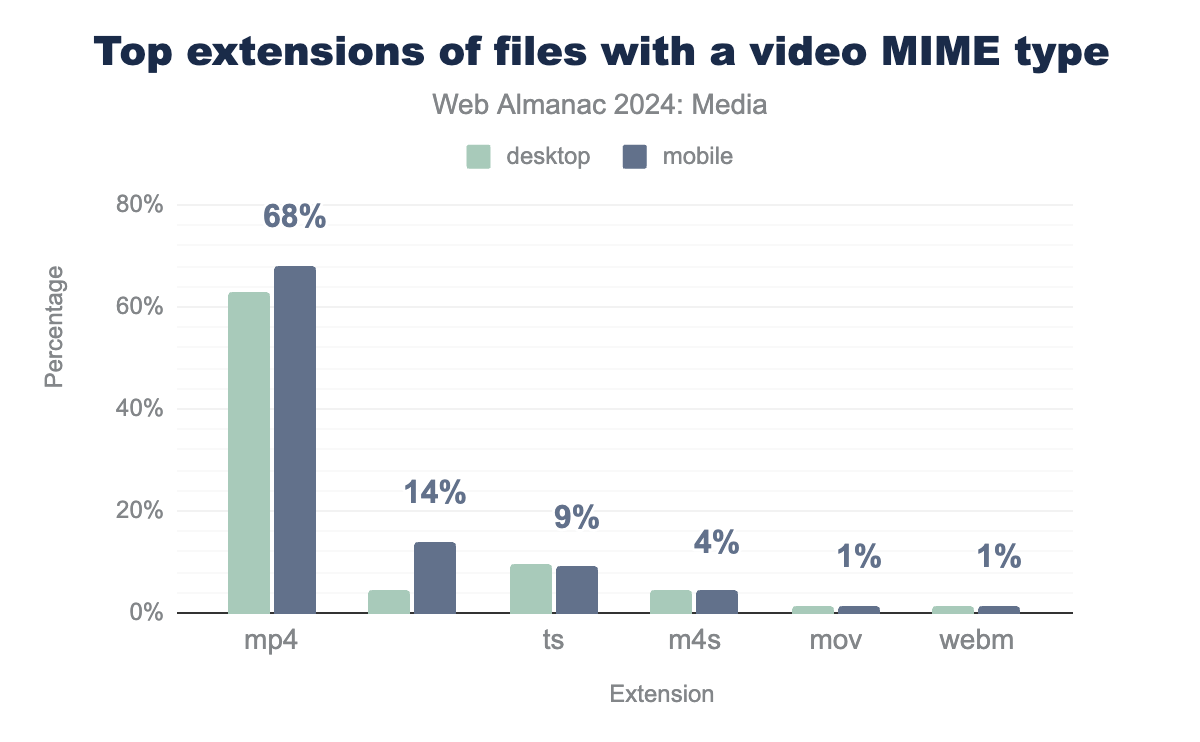

フォーマットの採用

2024年にサイトはどのようなフォーマットを配信しているでしょうか?普遍的なサポートを享受しているMP4が王様です:

.mp4の次に最も一般的な拡張子は、拡張子なし、.ts、.m4sの3つです。このトリオは、<video>要素がHLSまたはMPEG-DASHを使用した適応ビットレートストリーミングを採用している場合に配信されます。.mp4または適応ビットレートストリーミング以外のものを配信する動画要素はまれで、見つかった拡張子のわずか4%しかありません。

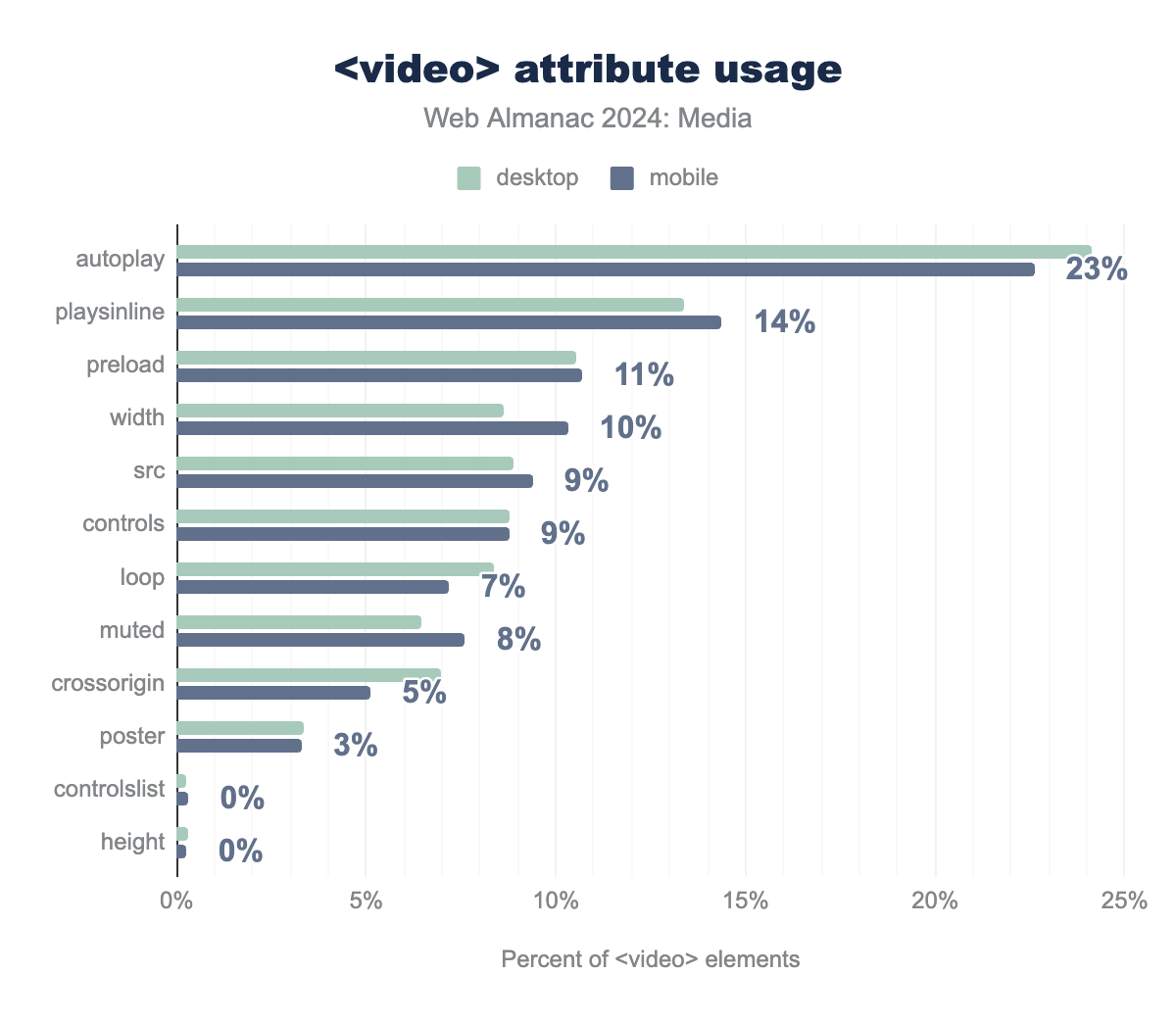

埋め込み

<video>要素は、作者が動画がどのように読み込まれ、ページ上で表示されるかを制御できるようにするいくつかの属性を提供しています。以下は、使用頻度順に並べたものです:

playsinlineとautoplayの両方が2022年から3パーセントポイント増加していますが—これはおそらくGIFと同じ役割を果たす短いインライン動画の採用増加を表していますが—過去数年間で最も大きく変動したのはpreloadで、その使用率は6パーセントポイント減少しています。

これは2020年代を通じて見てきたトレンドの継続であり、その理由についての私たちの仮説は2022年と同じままです。ブラウザは作者よりもエンドユーザーのコンテキストについてより多くを知っています。preload属性を含めないことで、作者はますますブラウザの邪魔をしなくなっています。

srcとsource

src属性は<video>要素のわずか9%にしか存在しません。ウェブ上の残りの多くの<video>要素は<source>子要素を使用しており、これにより作者は—理論的には—異なるコンテキストで使用するための複数の代替動画リソースを提供できます。

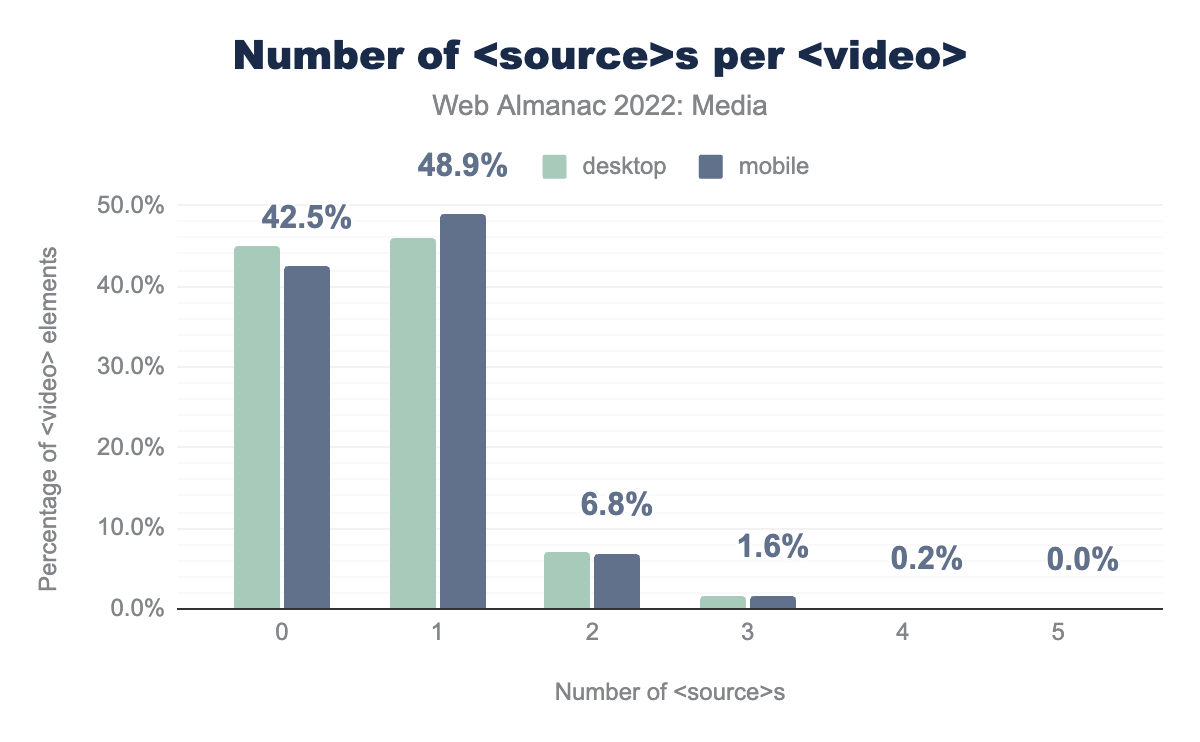

<video>あたりの<source>の数。

しかし、<source>子要素を持つ<video>要素のほとんどは1つしか持っていません—複数の<source>を持つ<video>要素は10個に1個だけです。

結論

以上が2024年のウェブ上のメディアの現状のスナップショットであり、過去数年間でどのように変化したかの概観です。メディアがウェブのユーザー体験にいかに普遍的で重要であるかを見てきました。また、サイトがメディアを効果的に配信している方法と、そうでない方法についても検討しました。

おそらく驚くことではありませんが、ウェブ上の画像はより大きくなっていることがわかりました。画像のピクセル数やレイアウトの寸法のどちらを数えても、数値は上昇しています。そのため、圧縮率の向上(一部は最新の画像フォーマットの採用増加による)にもかかわらず、画像の合計バイトサイズも増加しています。

同様に、動画側で見られた最も顕著な変化は、単に2年前よりもはるかに多くの動画が使用されているということでした。ウェブはますます視覚的になり続けています。

これらの主要な発見の他に、今年の分析で見つかった注目すべき励みになる点としては、広色域カラースペースの採用の最初の兆し、遅延読み込みの継続的な急速な採用、そしてレスポンシブ画像マークアップの着実な増加が含まれます。

一方、落胆させられる点としては、altテキストがないか無意味な<img>要素の膨大な数、不必要に遅いLCP時間につながる遅延読み込みの過剰使用、GIF使用の謎めいた(小さいながらも)増加、そしてsizesの精度がさらに悪化したことが見られました。

2025年のウェブでより効果的な視覚的コミュニケーションが実現することを願っています!