Privacy

Introduction

Whether it is to keep up-to-date with the latest news, stay in touch with friends via online social media, or look for a nice dress or sweater to buy, many of us rely on the web to provide us with these services and information with just a couple of clicks. A side-effect of spending almost 7 hours per day on the internet on average, is that a lot of our browsing activities, and thus indirectly our personal interests and data, is captured or shared with a plethora of online web services and companies.

As advertisers try to provide users with ads that are most relevant to them (as these are the ones they are most likely to interact with), they often resort to third-party tracking to infer the user’s interest. In essence, a user’s online activities are tracked step by step, providing trackers, in particular those that are most prevalent on the web, with a heap of information, most of which is probably not even relevant to infer the user’s interests. On top of that, users are generally not given an adequate choice to opt-out of this.

In this chapter, we explore the current state of the web in terms of privacy. We report on the ubiquitousness of third-party tracking, the different services that make up this ecosystem, and how certain parties are trying to circumvent the protective measures that users are employing to protect their privacy (for example, blocklist-based anti-trackers). Furthermore, we also look into how websites are trying to enhance the privacy of their visitors, either by adopting features that limit the information shared with other parties, or by being compliant with privacy regulations such as GDPR and CCPA.

Online tracking

Tracking is one of the most pervasive web technologies on the web—we find that 82% of desktop websites (80% for mobile) include at least one third-party tracker. By following users’ behavior online, these tracking companies can create profiles of them, which can be used for personalized advertising, give insights to website owners on who visits their websites, or use this information to distinguish legitimate users from (unwanted) bots. In this section, we explore the different techniques that are used to track the activities of users online and look at how trackers aim to circumvent the various privacy features that aim to protect users from being tracked.

Third-party tracking

One of the most common forms of online tracking is through third-party services, where a website owner typically includes a third-party, cross-site, script that provides site analytics or shows advertisements to visitors. This script can then set a third-party cookie, and log which website the user visited. Whenever the user visits another website that includes the same third-party service, the cookie will be sent along to the tracker, allowing them to re-identify the user and link both website visits to the same profile.

The types of third-party services that are included—and by doing so are implicitly given the capabilities of tracking website visitors—somewhat vary. The two most common categories (as defined by WhoTracks.me) of such trackers are site analytics scripts (68% on mobile, 73% on desktop) and advertising (66% on mobile, 68% on desktop). These two are followed by a few other categories, some of which might not have a clear link to tracking: customer interaction (services that allow customers to easily send messages to the website owner), audio/video players (for example, YouTube embedded videos), and social (for example, Facebook “like” buttons).

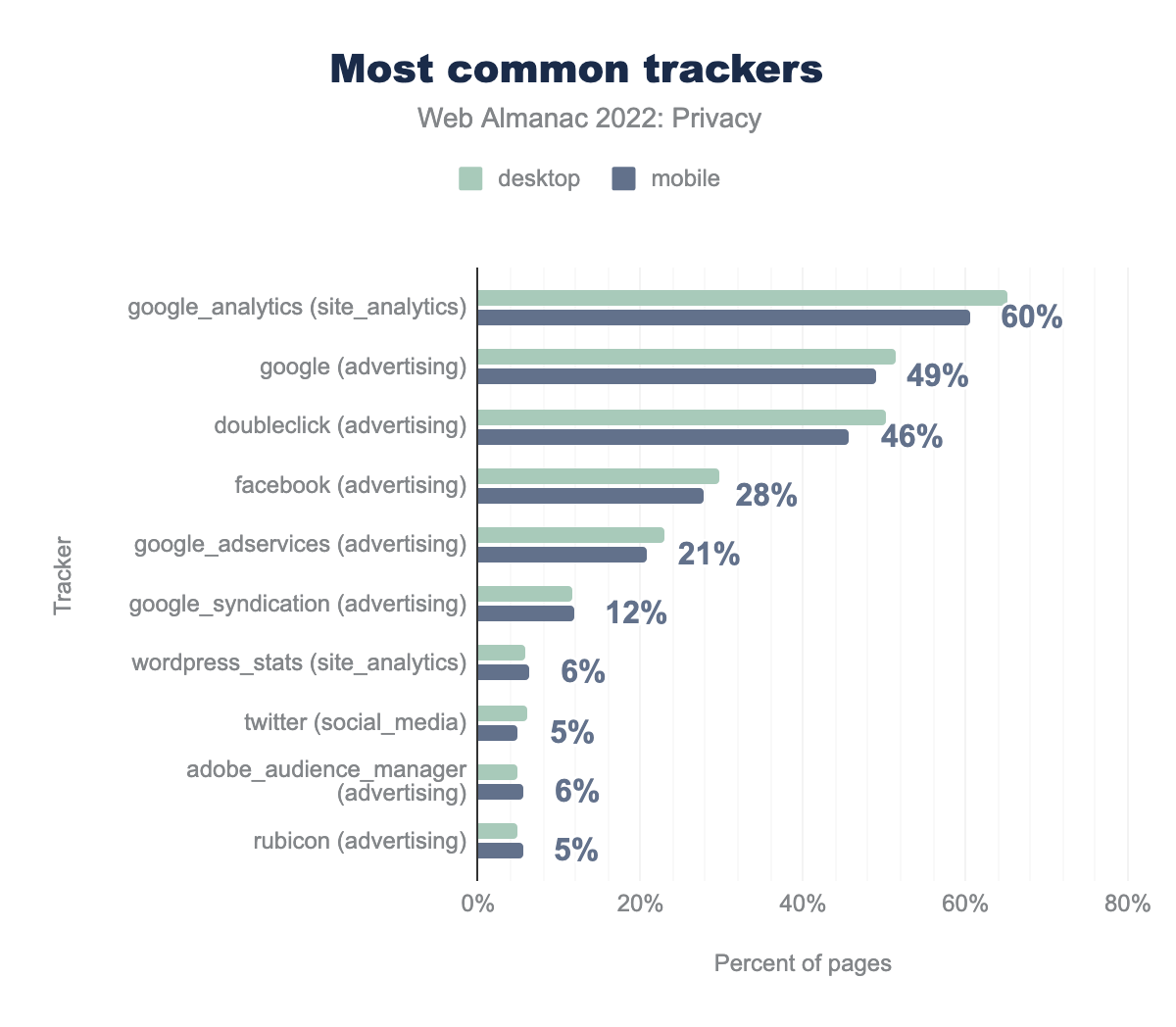

For a tracker to successfully profile a user, they need to be included in a large fraction of websites in order to be able to track a significant fraction of users’ online activities. When we look at the most common trackers, these are mostly the “usual suspects”. Of the top 10 most common trackers five are affiliated with Google. Also included in this list are popular social networks such as Facebook and Twitter.

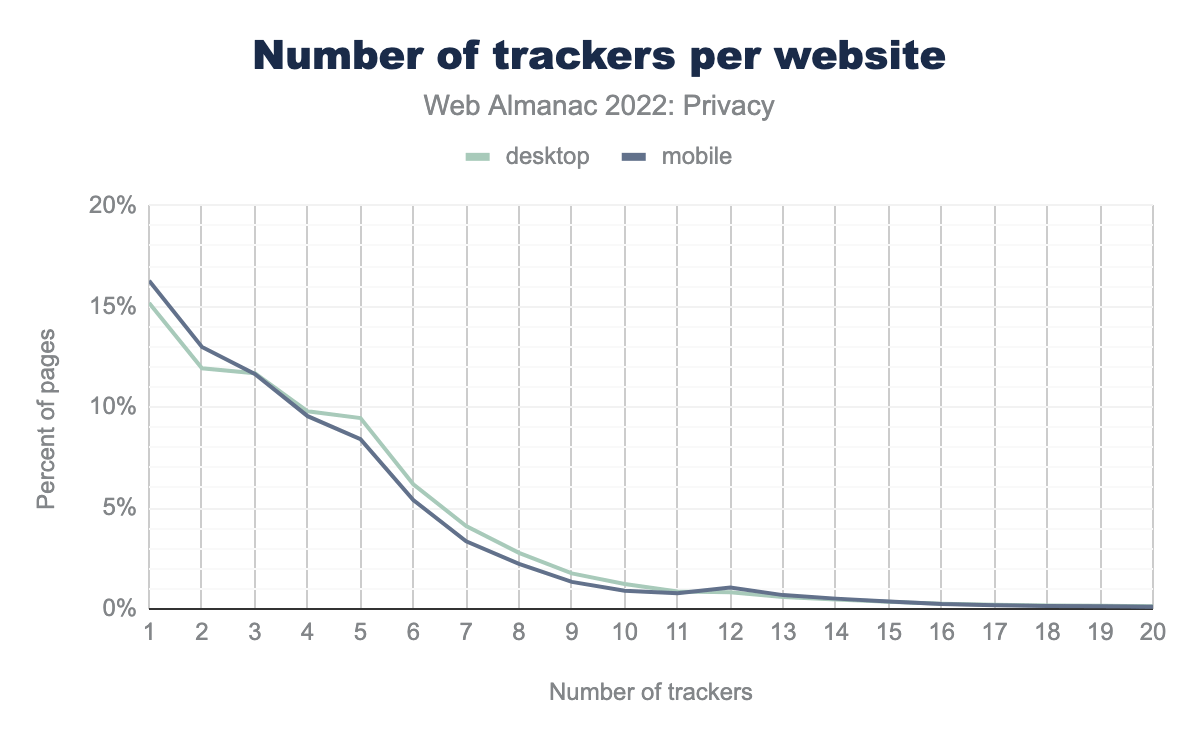

Websites might want to make use of multiple third-party services, and thus may include multiple trackers in their website (be sure to check out the Third Parties chapter for a deep dive into which third parties are included on the web!). We find that approximately 15% of desktop sites and 16% of mobile sites include “just” one tracker. Unfortunately, this means that it is in fact more common for websites to include multiple trackers. We even found one website that included 126 different trackers!

(Re)targeting

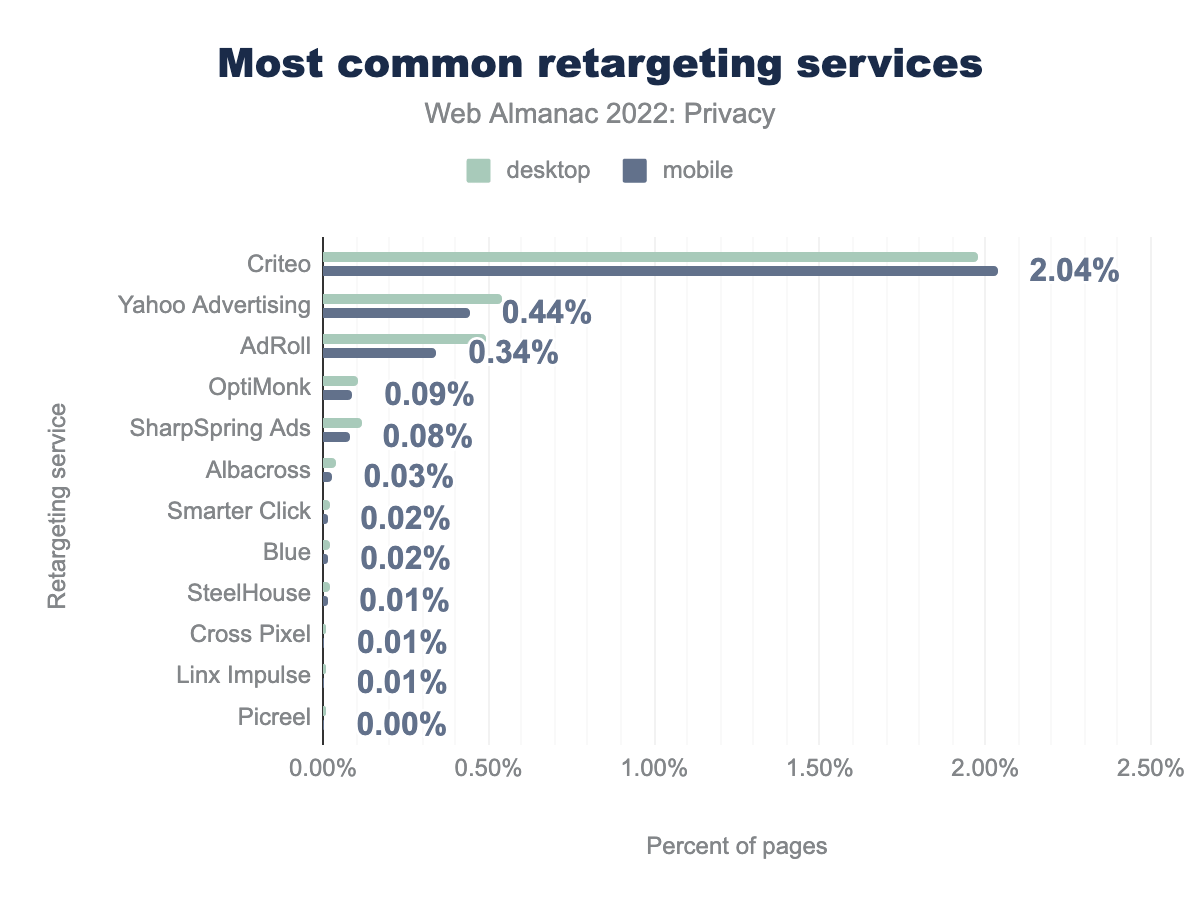

When browsing the web, we often encounter advertisements for products that we recently looked up. The reason for that is ad retargeting. When a website detects that a user might be interested in a specific product, they report this to the tracker and/or advertiser, who will later on, when the user is visiting other, unrelated websites, show advertisements for the product that the user is supposedly interested in, in an attempt to nudge them into purchasing it.

The tracker offering most of the purely retargeting services is Criteo, with a prevalence of 1.98% on desktop and 2.04% on mobile. It is followed by Yahoo Advertising and AdRoll, which collectively make up less than half of Criteo’s market share. The most widely used retargeting service of last year, Google Tag Manager, does not show in these results as it is now classified under the “tag managers” Wappalyzer category. Although this service is used for retargeting, it does so indirectly, by the inclusion of retargeting tags which are detected separately.

Third-party cookies

As mentioned before, the most established way to track users across different websites is by means of third-party cookies. With recent changes in browser policies, cookies will no longer be included in cross-site requests by default. In technical terms this means that most browsers set the SameSite attribute of cookies to the default value Lax. Websites can override this by explicitly setting the value themselves. This has been happening on a large scale: of the third-party cookies that set the SameSite cookies, 98% of them set it to the value None, allowing them to be included in cross-site requests. Furthermore, the expiration time of the cookie also determines how long it remains valid; we find that the median lifetime of a cookie is 365 days. For a deeper dive into cookies and cookie attributes, please refer to the Security chapter.

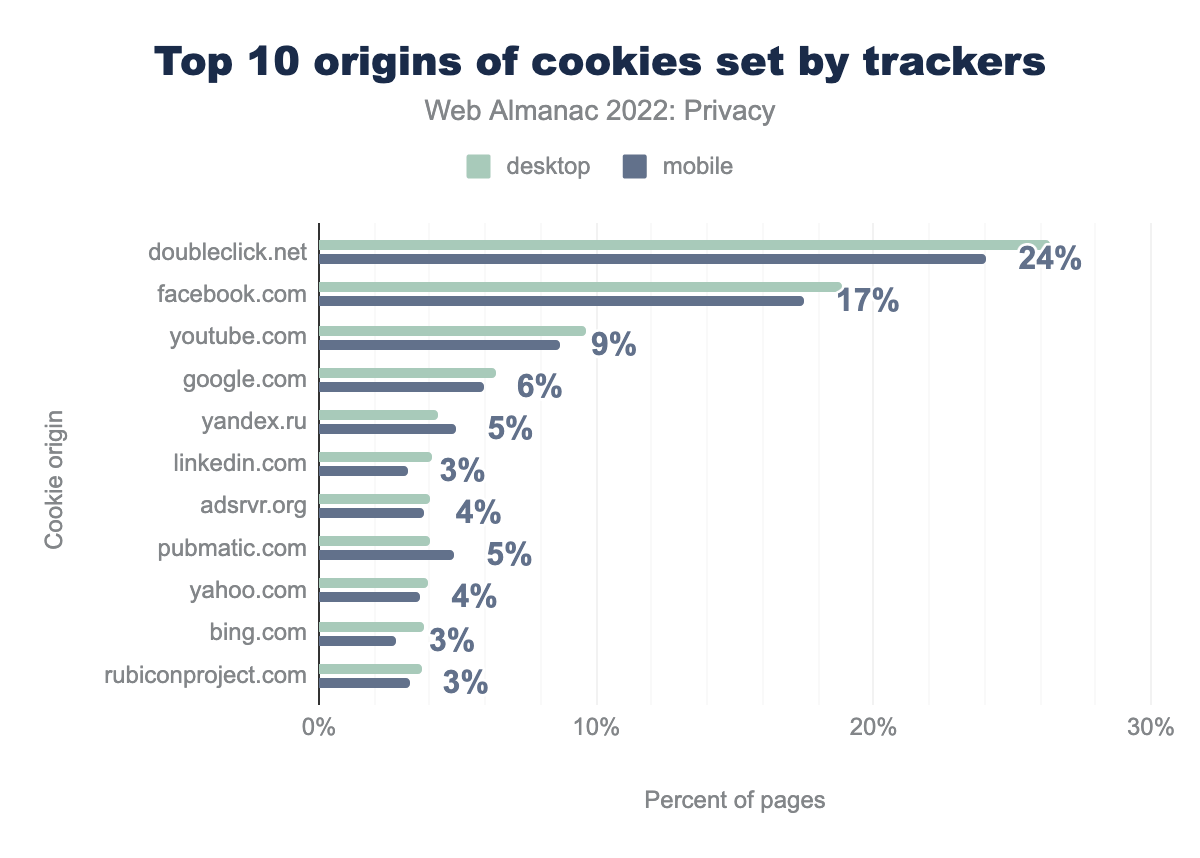

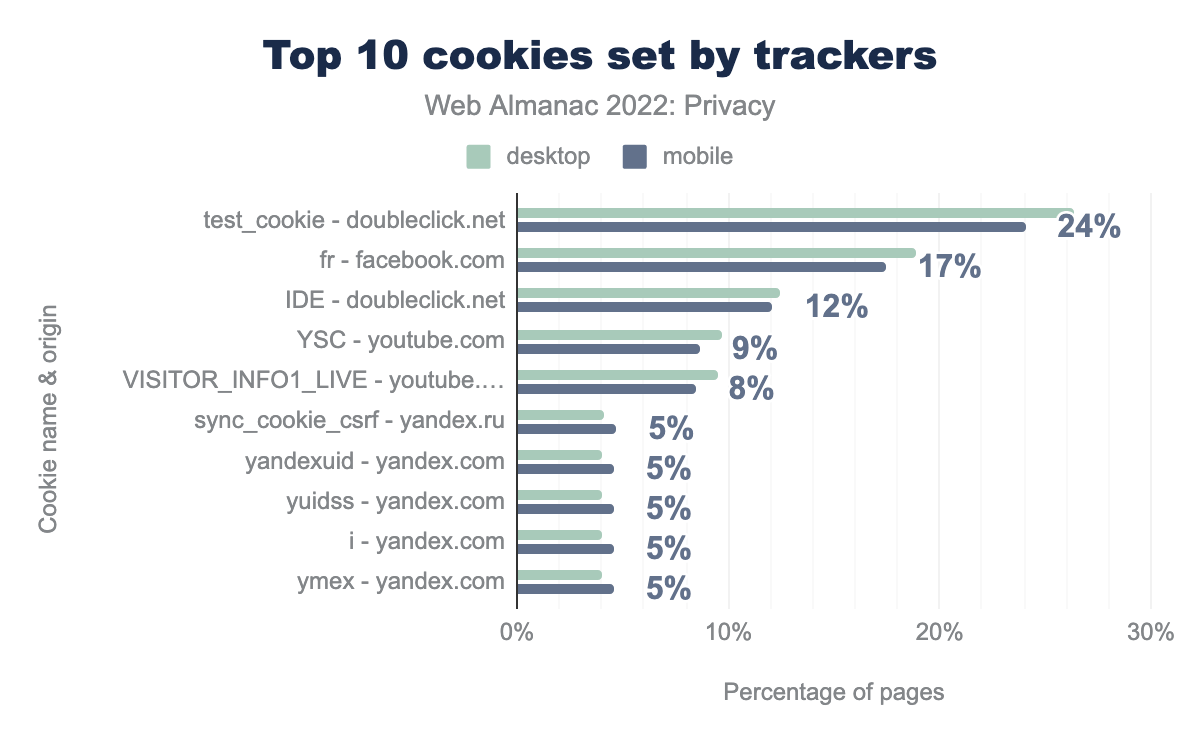

For a large part, the third-party trackers that set cookies largely coincide with the third parties that are included on websites. However, the most popular third-party tracker, Google Analytics, is not as prevalent here. This can be attributed to the fact that Google Analytics sets a first-party cookie (_ga), which according to their definition “is unique to the specific property, so it cannot be used to track a given user or browser across unrelated websites”. Nevertheless, the most common tracking domain that sets third-party cookies, doubleclick.net, is still Google affiliated. The other domains on the list are associated with social media and advertising.

test_cookie, which was set by doubleclick.net can be found on 26% desktop sites and 24% mobile sites respectively, fr set by facebook.com was found on 19% and 17%, IDE set by doubleclick.net on 12% and 12%, YSC set by youtube.com on 10% and 9%, VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE set by youtube.com on 10% and 8%, sync_cookie_csrf set by yandex.ru on 4% and 5%, yandexuid set by yandex.com on 4% and 5%, yuidss set by yandex.com on 4% and 5%, i set by yandex.com on 4% and 5%, and finally ymex set by yandex.com on 4% and 5%.When looking at the most common third-party cookies, we again see several tracking domains, lead by the test_cookie from doubleclick.net—a cookie with a lifespan of 15 minutes that is used for functionality purposes according to its description. This cookie is followed by the fr cookie set by facebook.com—a cookie “used to deliver, measure and improve the relevancy of ads, with a lifespan of 90 days” according to its definition. The rest of the 10 most prevalent third-party cookies are set by YouTube and Yandex.

Evasion technique: fingerprinting

As more and more browsers develop countermeasures for cookie-based tracking, and giving users more control to block third-party cookies, some trackers aim to circumvent these protections. One such technique is fingerprinting, where browser-specific features (for example, installed browser extensions), OS-specific features (for example, installed fonts) and hardware-specific features (for example, differences in rendering complex composition based on which GPU is used) are used to create a unique fingerprint of the user. This fingerprint then allows the tracker to re-identify the same user across different, unrelated websites.

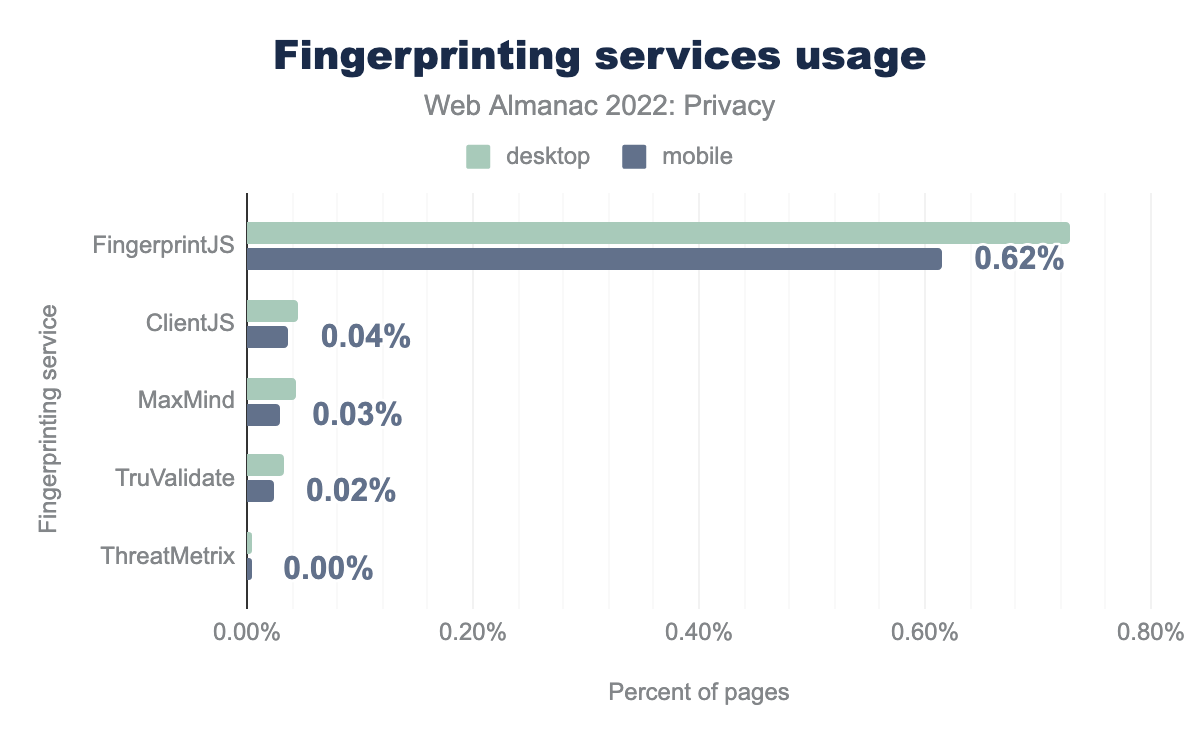

In our analysis, we looked for five different, known fingerprinting libraries and we find that the most prevalent library used on the web to perform fingerprinting is FingerprintJS, which we find on 0.62% of all websites. Most likely this is because the library is open source, and has a free version. Compared to our measurements last year, we find that the use of fingerprinting has approximately stayed the same.

Evasion technique: CNAME tracking

As most of the tracking countermeasures focus on blocking or disabling third-party cookies, another way to circumvent these protections is to use first-party cookies instead. Here, the tracker is cloaked using a CNAME record on a subdomain of the website it is embedded in. When the tracker then sets a cookie, it will be considered a first-party cookie. A limitation of CNAME-based tracking is that it can only be used to track a user’s activities within a specific website, although the tracker could still rely on cookie syncing to match visits across multiple sites together.

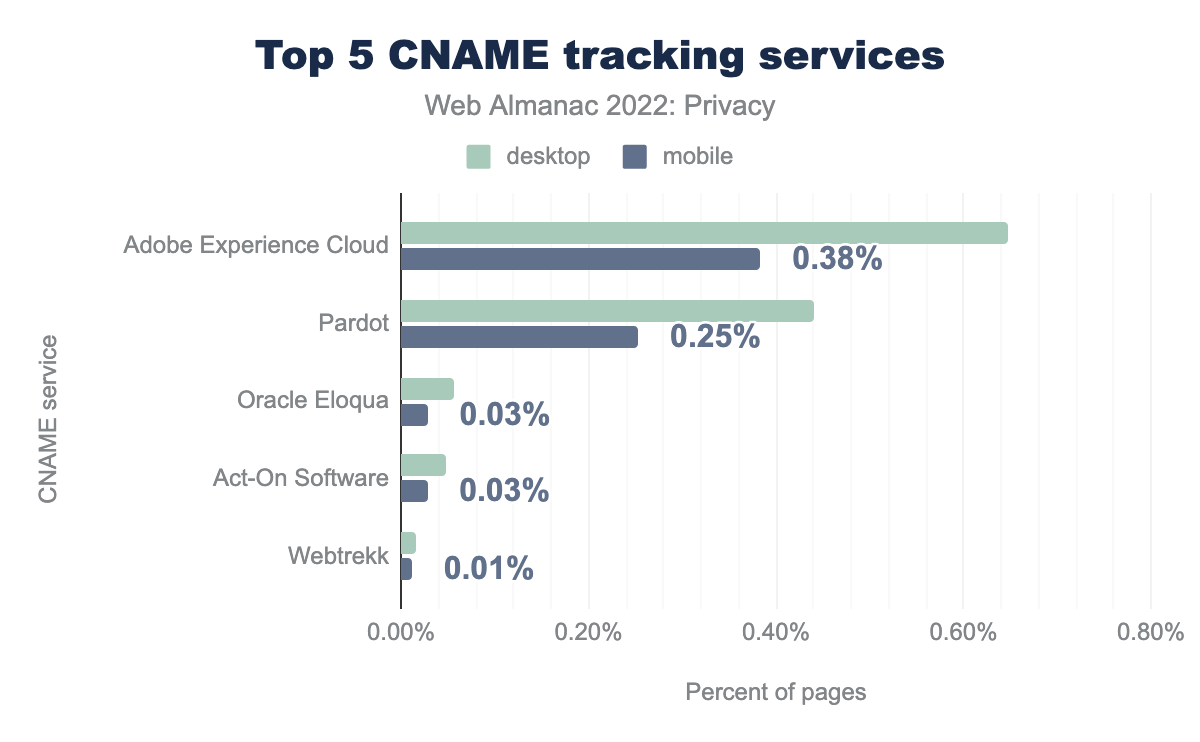

By analyzing the various CNAME trackers, we find that the market share is mainly concentrated around two main services: Adobe Experience Cloud (0.65% on desktop and 0.38% on mobile) and Pardot (0.25% on desktop and 0.44% on mobile). Interestingly, the adoption of CNAME tracking is significantly higher on websites visited with a desktop browser compared to those visited on mobile. Presumably this is because there are fewer privacy-preserving mechanisms on mobile browsers—for example, most of the popular browsers on mobile do not support extensions.

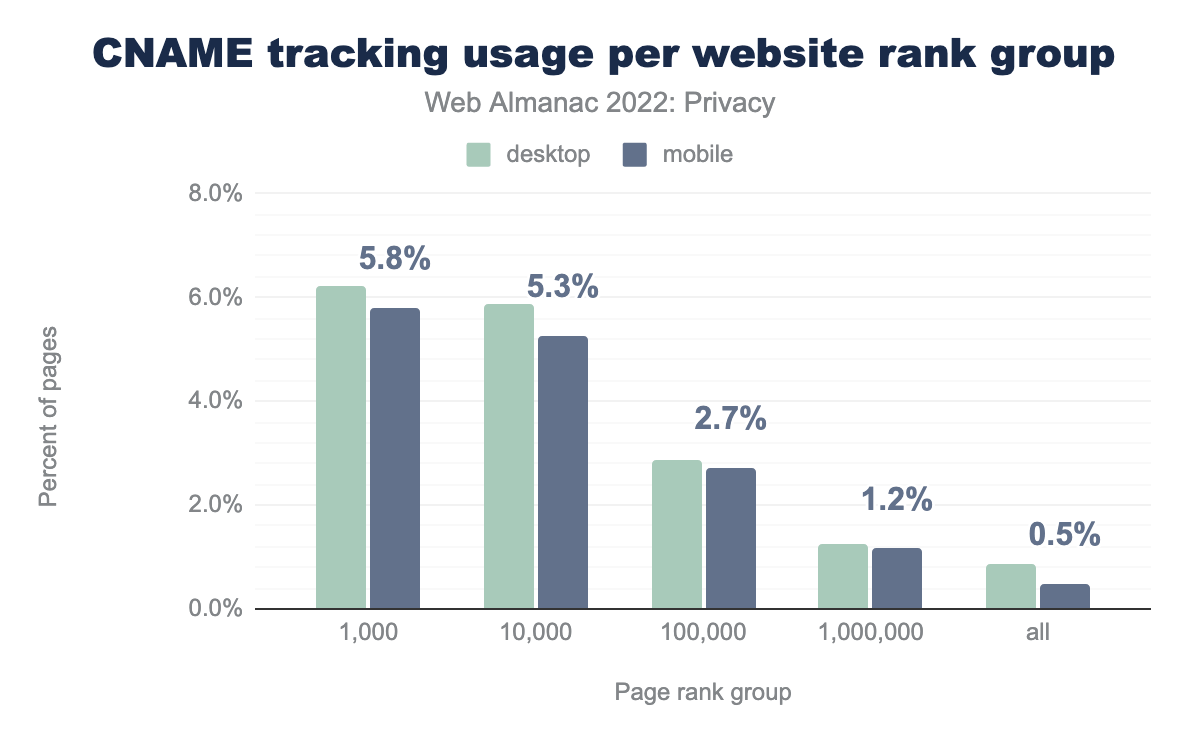

Although the overall prevalence of CNAME-based tracking might not seem very high (0.9% on desktop websites, 0.5% on mobile sites), its adoption is mainly concentrated on highly popular websites. Within the top 1,000 most visited websites 6.2% of desktop sites and 5.8% of mobile sites embed a CNAME tracker. This means that users are quite likely to encounter such trackers when browsing the web.

Access to (sensitive) data from the browser

Browsers have an abundant number of APIs, which provide developers with useful mechanisms to interact with different components in whichever way they want. Several of these APIs can also be used to extract information from sensors or other peripherals connected to the user’s device. While most APIs provide a limited amount of information (such as the orientation of the screen), others provide very detailed information (for example, the accelerometer and gyroscope), which could be used for device fingerprinting, or even inferring which password a user types based on the movements they make with their mobile device.

Sensor events

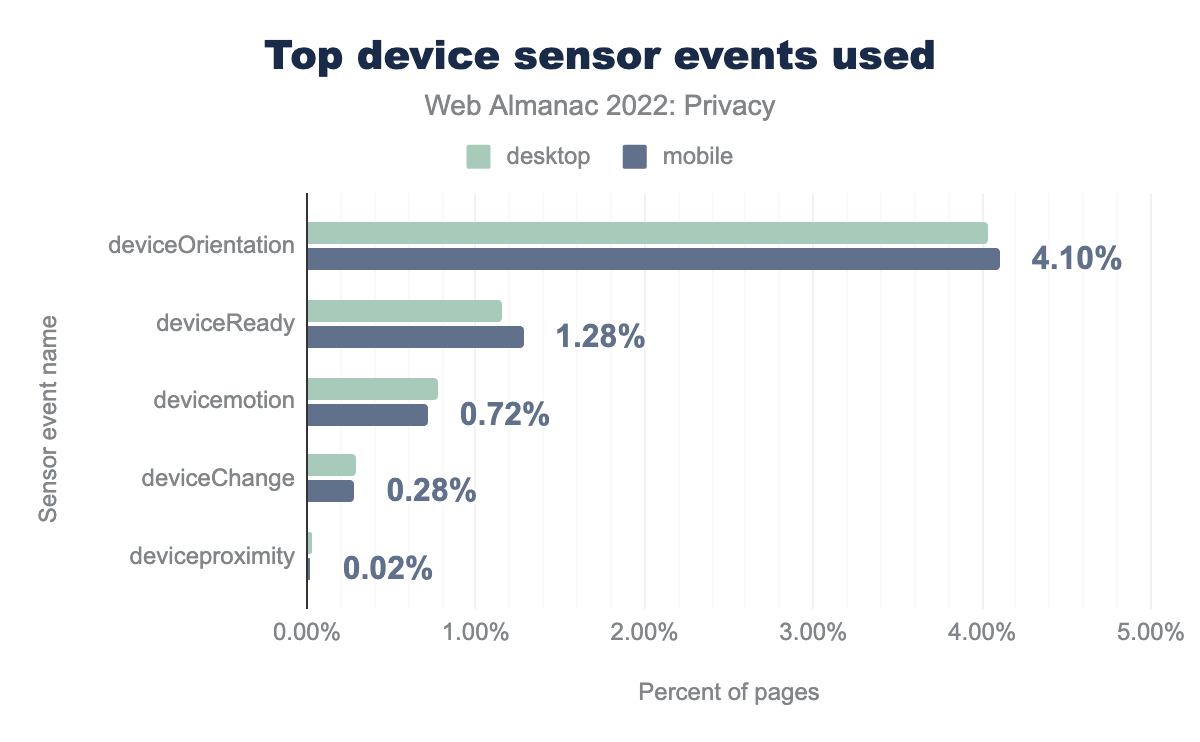

deviceOrientation was found to be used on 4.04% desktop and 4.10% mobile sites, deviceReady on 1.16% and 1.28%, devicemotion on 0.78% and 0.72%, deviceChange on 0.29% and 0.28%, and finally the deviceproximity event was found on 0.03% desktop and 0.02% mobile sites.We find that the most prominent sensor event that websites listen for is the deviceOrientation event, which fires when the device changes from portrait to landscape mode or vice versa. It is used on 4.0% of desktop websites and 4.1% of mobile websites. The usage is likely this high (relatively) because websites might want to update elements of the layout when the orientation of the device changes.

Media devices

Using the MediaDevices API, web developers can use the enumerateDevices() method to get a list of all media devices connected to the user’s device. While this feature is useful to determine whether a user has a camera or microphone connected to initiate a video call, it can also be used to gather information about the system’s environment for fingerprinting purposes. We find that 0.59% of desktop websites and 0.48% of mobile sites try to access the list of connected media devices—note that our crawler does not interact with the site, nor click on any buttons. Interestingly, the usage of this API has significantly reduced since last year, when the prevalence of sites accessing the list of media devices was 12 times higher. Most likely this is due to a popular library that no longer calls the API.

Geolocation

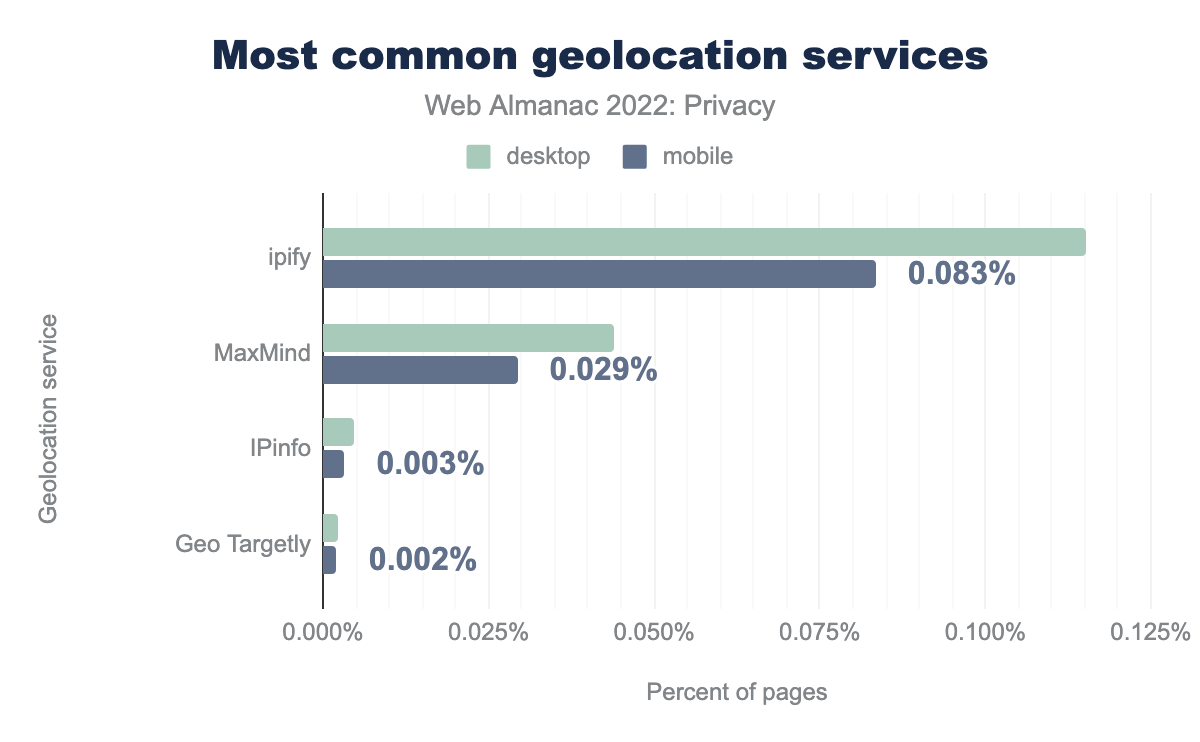

A lot of the content that is served to us is localized based on the location that we’re visiting websites from. For web developers to determine where a visitor is from, they can use third-party geolocation service. These will determine a user’s location based on their IP address. Although this geolocation is typically used on the back-end, we do find some usage also in the front-end: 0.115% of desktop sites and 0.083% of mobile sites contact ipify to determine the user’s IP location.

As the IP-based geolocation service can be quite inaccurate, especially when users rely on a VPN to hide their original IP address, websites might request a more granular location through the Geolocation API. Of course, access to this (privacy-intrusive) API is still guarded by a permission that users manually need to provide. Yet, we find that 0.65% of desktop sites and 0.61% of mobile sites try to access the user’s current location upon a visit to the home page, without any user interaction. Interestingly, we still find 574 desktop sites—down from 900 last year—that try to access the feature while the page was loaded over an insecure connection. Due to the sensitive nature of the data that this feature provides, most browsers restrict its use to secure origins.

Established controls to improve visitor’s privacy

As websites include a lot of content (scripts, plugins, etc.) from third parties that they might not entirely trust, they might want to protect their users’ privacy from these third parties. Next, we explore the various controls that can be used to restrict the features or data that third parties have access to, or that make it explicitly clear which information a website wants to obtain from a user.

Permissions Policy

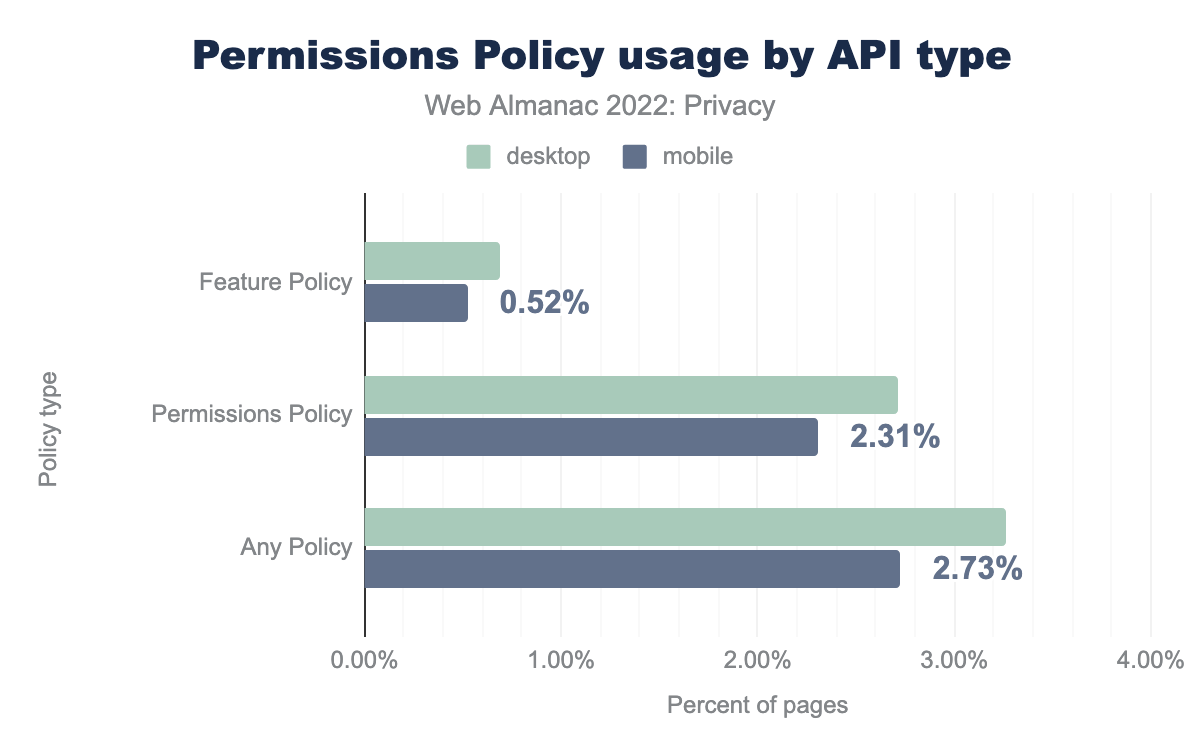

By default, any third-party script can access the same browser features as the website they’re embedded in. In order to limit the features that will be enabled for the website, the website can make use of the Permissions Policy. Through an HTTP response header the website can indicate which features it wants to allow. For instance, if the microphone feature is not included in this list, none of the scripts embedded in the web page can use it. Although the policy is fairly new, we are seeing an adoption of 2.71% on desktop sites and 2.31% on mobile sites.

The Permissions Policy supersedes the Feature Policy, which can still be found on 0.69% of desktop sites and 0.52% of mobile sites. By default most of the features regulated by the Permissions Policy are disabled in cross-origin iframes, they can be explicitly enabled through the allow attribute. We find that 15.18% of desktop sites and 14.32% of mobile sites make use of this feature. For a more detailed analysis on the use of the allow attribute on iframes, please refer to the Security chapter.

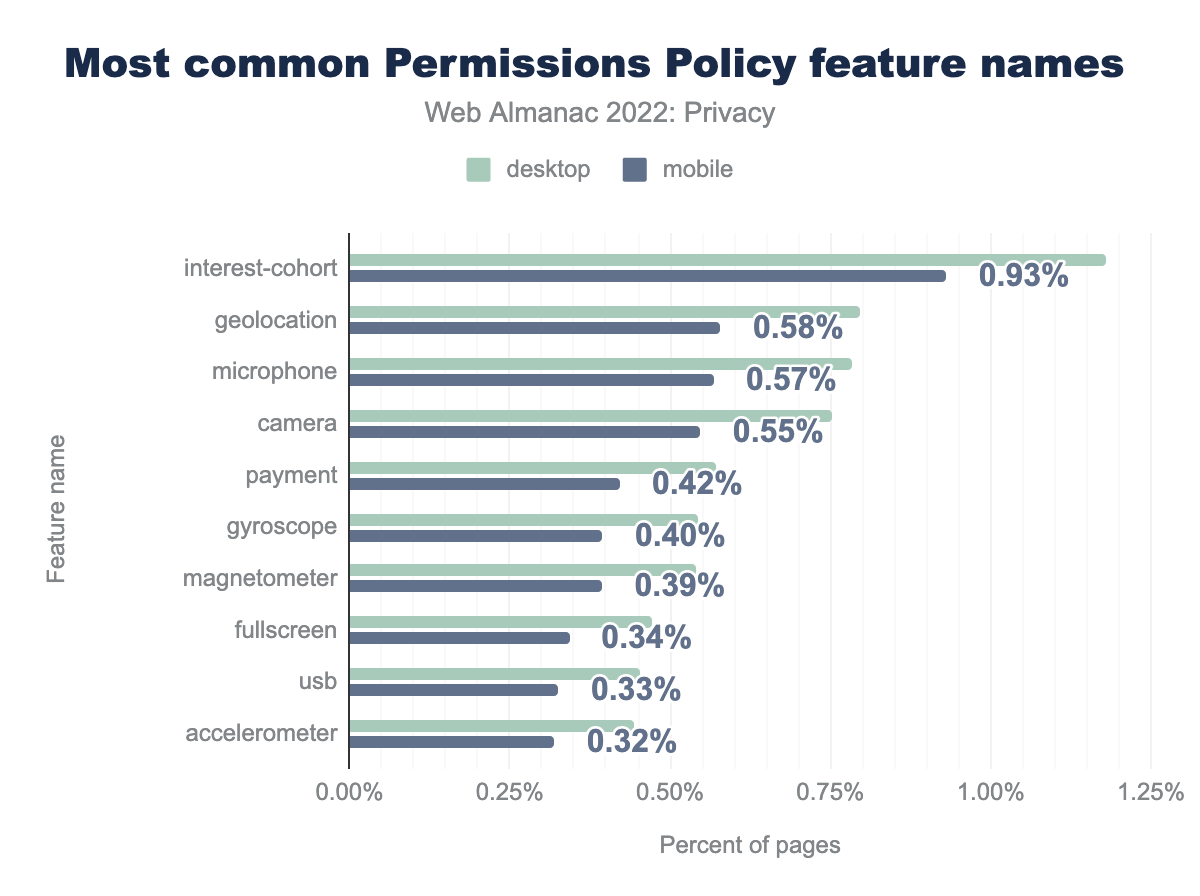

interest-cohort of the Permissions Policy was present on 1.18% desktop and 0.93% mobile sites respectively, the geolocation feature was specified on 0.80% and 0.58% sites, microphone on 0.78% and 0.57%, camera on 0.75% and 0.55%, payment on 0.57% and 0.42%, gyroscope on 0.54% and 0.40%, magnetometer on 0.54% and 0.39%, fullscreen on 0.47% and 0.34%, usb on 0.45% and 0.33%, and finally accelerometer was defined on 0.44% desktop and 0.32% mobile sites.When we look at the directives that are used in the Permissions Policy, we see a similar usage compared to last year, with the exception of the one that’s most widely used in 2022, namely interest-cohort. This directive can be used to limit the access to the now-defunct FLoC API. Presumably, this increase can be attributed to the various shortcomings of FLoC (increases fingerprinting surface, reveals potentially sensitive information about users, etc.) where website owners, providers and libraries took an active step in trying to protect the privacy of their users.

Referrer Policy

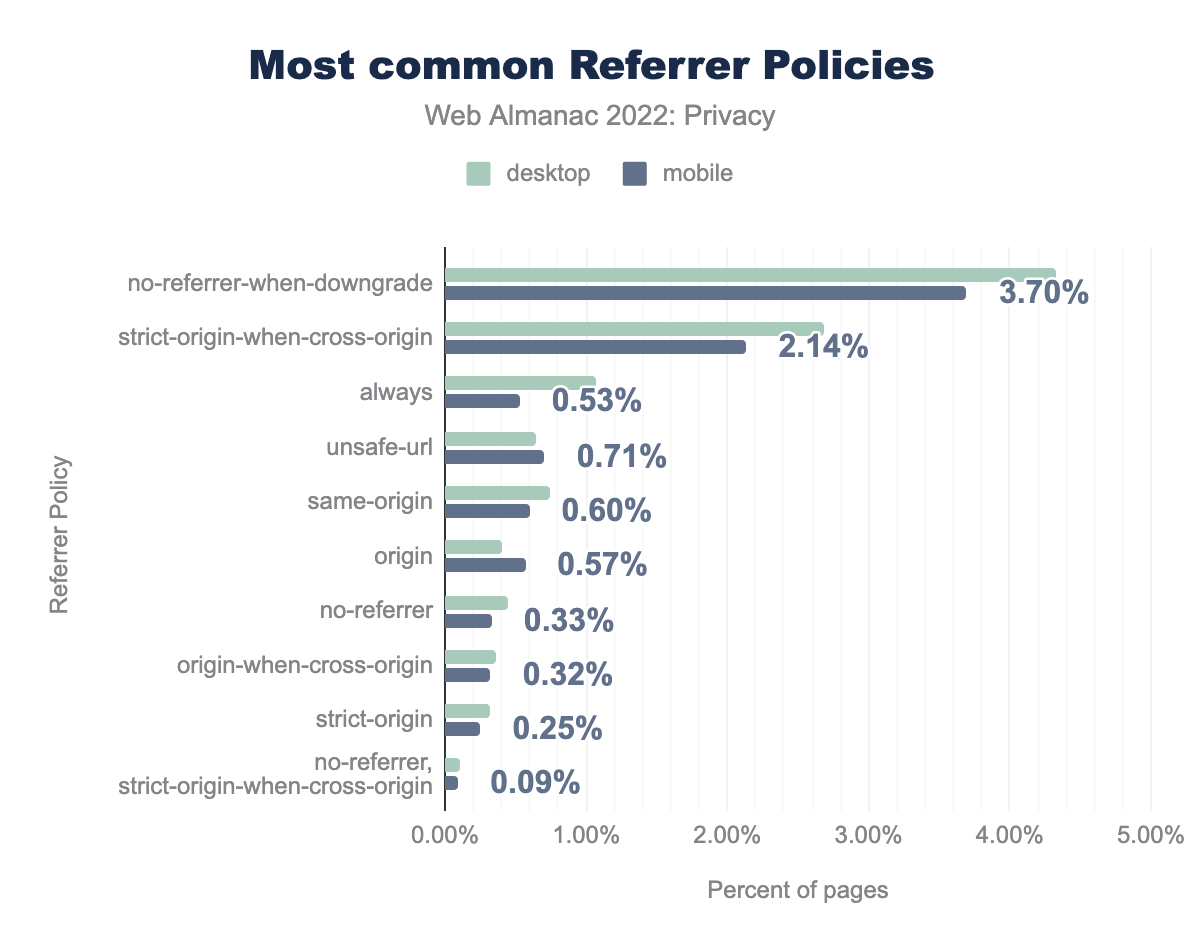

By default, most user agents will include a Referer header. In short, this reveals to third parties from which web site—or even page—a request was initiated. This is the case for any resource that was embedded in the web page, as well as for the request that was initiated after a user clicked on a link. Of course, this has the undesirable side-effect that these third parties learn which website, or even which web page a specific user was visiting. By making use of the Referrer Policy, websites can limit the instances in which the Referrer header is included in requests and thus improve user privacy. We find that 12% of the desktop sites and 10-% of the mobile sites set such a document-wide policy, mostly via an HTTP response header.

no-referrer-when-downgrade was found on 4.33% desktop and 3.70% mobile sites respectively, strict-origin-when-cross-origin was found on 2.68% desktop and 2.14% mobile sites, always on 1.07% and 0.53%, unsafe-url on 0.64% and 0.71%, same-origin on 0.74% and 0.60%, origin on 0.41% and 0.57%, no-referrer on 0.44% and 0.33%, origin-when-cross-origin on 0.37% and 0.32%, strict-origin on 0.32% and 0.25%, and finally no-referrer, strict-origin-when-cross-origin was found on 0.11% desktop and 0.09% mobile sites.We find that the most common usage of the Referrer Policy is to not include the Referer header on downgrade requests, that is, HTTP requests initiated on an HTTPS-enabled page. Unfortunately, this still leaks the page that the user is visiting in most scenarios—in HTTPS-enabled requests. We do see that 2.7% of desktop sites and 2.1% of mobile sites aim to hide the specific web page that a user is visiting through the strict-origin-when-cross-origin policy, which is now most browsers default when a policy is not specified.

User-Agent Client Hints

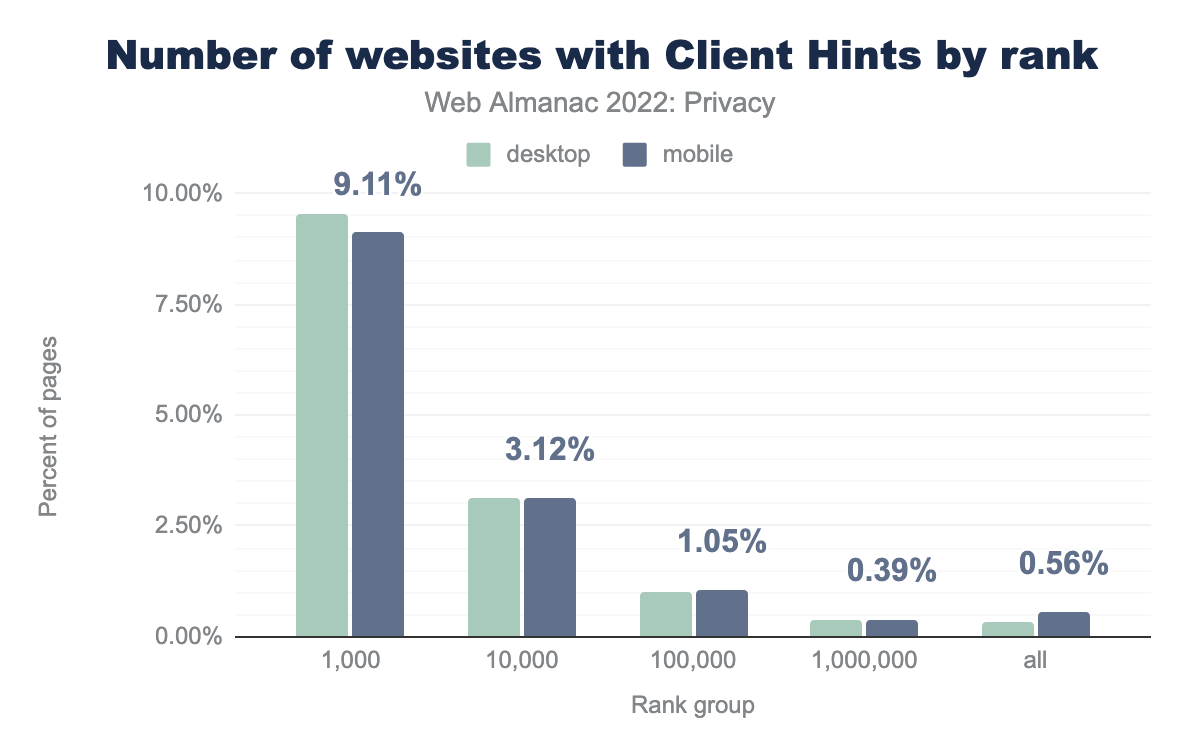

In an effort to reduce the information that is revealed about the browser environment, and more specifically the User-Agent string, the User-Agent Client Hints mechanism was introduced. Through this feature, websites that want to access certain information about the user’s browsing environment (browser version, operating system, etc.) now have to set a header (Accept-CH) in the first response, upon which the browser will send the requested data in subsequent requests. Among other benefits, this feature reduces the fingerprinting surface and allows browsers to intervene in sending certain data, for example, via the Privacy Budget proposal.

When we look at the adoption of sites that respond with the Accept-CH header in comparison with the results from last year (top 1k: 3.56%, top 10k: 1.44%), we see a significant increase in adoption, almost 3x for the most popular sites. Presumably, this increase in adoption is related to the fact Chromium has been reducing the information that is shared in the User-Agent string (through the User-Agent Reduction plan).

We find that the sites that make use of User-Agent Client hints, generally request access to a relatively large number of properties, limiting the benefit of what browsers aim to achieve through efforts such as User-Agent Reduction. It will be interesting to see in the near future how/whether browsers will limit the practices of acquiring a lot of information about the user’s browsing environment.

New efforts to improve privacy by the browser

Over the last few years, the average web user has become increasingly conscious about their online privacy. On the one hand, the many data breaches, which just seem to keep on happening and getting bigger and bigger, have left very few unaffected. On the other hand, the fact of the ubiquitous tracking of users through third-party cookies is becoming increasingly well known within the general population. As a result, more and more users are starting to expect their browser to protect their privacy, and give them more control over the tracking of online behaviors. Browser vendors, online publishers and ad-tech companies have heard this demand for improved privacy, and have proposed the Privacy Sandbox—an initiative led by Google Chrome.

Privacy Sandbox Origin Trial

At the time of publishing this year’s Web Almanac, Privacy Sandbox features are not yet available for general use. Websites and web services—such as ads, which are typically shown in iframes—can however participate in early testing of the Privacy Sandbox features, by making use of the Origin Trial. Note that this is only for users whose browser supports the feature—Privacy Sandbox features are only implemented in Chrome, and are still disabled by default at the time of this writing. This gives the web services access to three Privacy Sandbox-related APIs: Topics, FLEDGE, and Attribution Reporting.

| Origin requesting feature | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| https://www.googletagmanager.com | 12.53% | 10.99% |

| https://googletagservices.com | 11.05% | 10.52% |

| https://doubleclick.net | 11.04% | 10.51% |

| https://googlesyndication.com | 11.04% | 10.51% |

| https://googleadservices.com | 2.50% | 2.29% |

| https://s.pinimg.com | 1.49% | 1.21% |

| https://criteo.net | 0.64% | 0.41% |

| https://criteo.com | 0.59% | 0.37% |

| https://imasdk.googleapis.com | 0.10% | 0.07% |

| https://teads.tv | 0.04% | 0.03% |

The most prevalent services on the web that will test during the Origin Trial of Privacy Sandbox are: Google Tag Manager, Doubleclick, Google Syndication and Google Ad Services make up the top five on both desktop and mobile sites. These are followed by the social media site Pinterest, and other trackers and advertisers: Criteo, Google Ads SDK, and Teads.

Privacy Sandbox experiments

The Privacy Sandbox initiative consists of many different features that each touch upon different aspects, and aim to still support the current common actions that users perform on the web when third-party cookies are phased out. As most features are still under active development, websites have not adopted them yet (with the exception of services opting-in to the PrivacySandboxAdsAPIs Origin Trial).

For some time the Origin Trial for various Privacy Sandbox features was divided into separate trials, one for each feature. Although these trials do not have any effect in modern browsing environments, some web services did opt-in to them and forgot to remove the Origin-Trial response header.

For example, we find that on 34,128 sites a web service opts-in to the ConversionMeasurement Origin Trial, which at one point gave them access to the Attribution Reporting API (previously called the Conversion Measurement API). This API is used to track the conversion of a user clicking an ad to a purchase, for example.

For the TrustTokens Origin Trial, which has also expired, we are still seeing 6,005 sites where a web service opts-in to it. This mechanism aims to allow websites to combat fraud by enabling one browsing context (for example, site) to convey a limited amount of information to another.

Interestingly, on more than 30,000 websites a web service is still opting-in to the InterestCohort origin trial, which would give them access to the interest group of the user of FLoC. However, due to privacy concerns with the API, it was no longer pursued and development was discontinued. It is superseded by the FLEDGE API, which aims to provide “on-device ad auctions to serve remarketing and custom audiences” and Topics API, which aims to allow advertisers to serve ads based on the interests of the user without the need of cross-site tracking.

Compliance with privacy regulations

The data privacy regulatory space continues to expand as the newest frontier of legislation. These regulations require organizations to be more transparent regarding their users’ data processing to protect their data. Following the advent of key data privacy regulations like General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and IAB Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF) v2.0, website providers took action to inform the users about processed data during the visit and take consent from these users to process their data also for non-functional purposes—for example, tracking and ads. This has led to us seeing cookie banners on websites more often because website providers notify their users or ask for consent mainly through (cookie) consent banners.

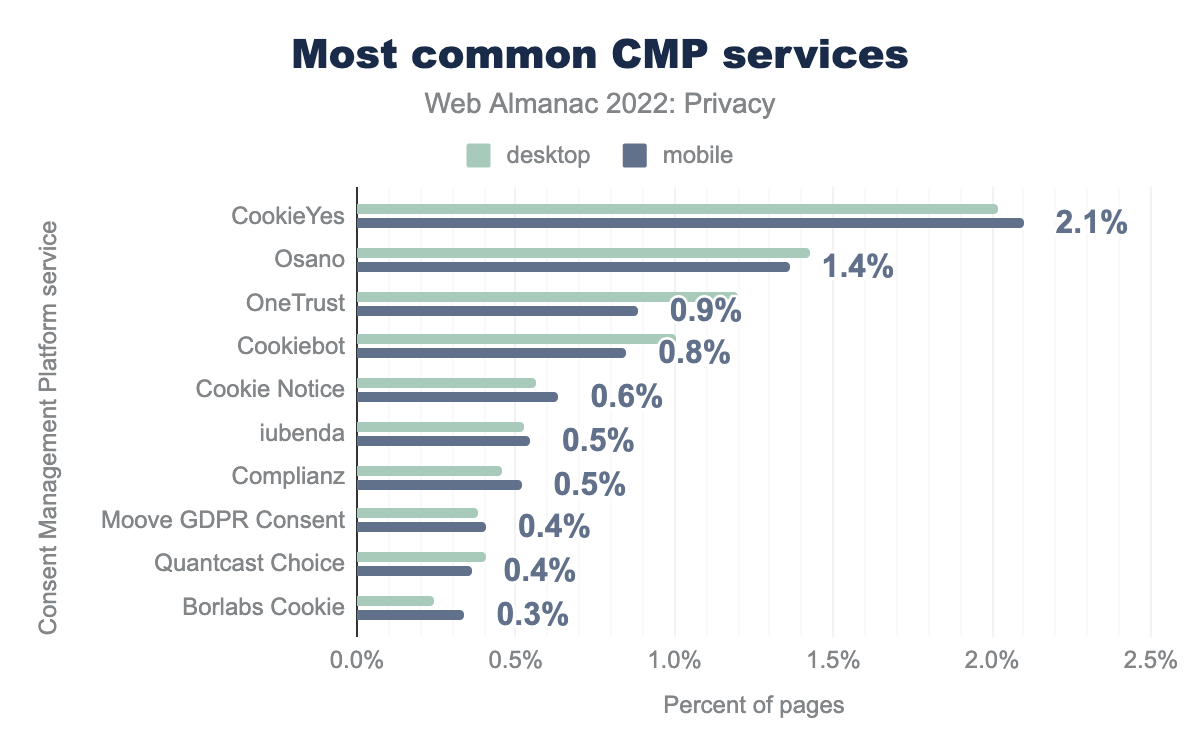

In most cases, users can interact with such consent banners and set which data should be processed. However, managing such tasks is not easy on our modern, sophisticated web, which is also getting more complicated. For this reason, website operators try to hand over this task to third parties—so-called Consent Management Platform (CMP). CMPs ensure that the cookies are used on the respective websites by the law. In the following, we discuss the use of CMPs and notification of privacy policy.

Consent Management Platforms

As we have already discussed, using the consent management platform should ensure that the website, in particular the behavior with cookies, should run in a legally compliant manner.

At this point, we would also like to note that the integration of CMP services does not always ensure that the websites remain legally compliant, as the studies in this field show (for example, Santos et al. and Fouad et al.).

Our analysis shows that CMP usage has increased from 7% to 11% since last year. So we recorded an increase of almost 60%. Also, this year we see that mobile is less involved than desktop—although the difference is minimal. We also see that the providers CookieYes (18%), OneTrust (64%), and Cookiebot (56%) have increased their market share since last year.

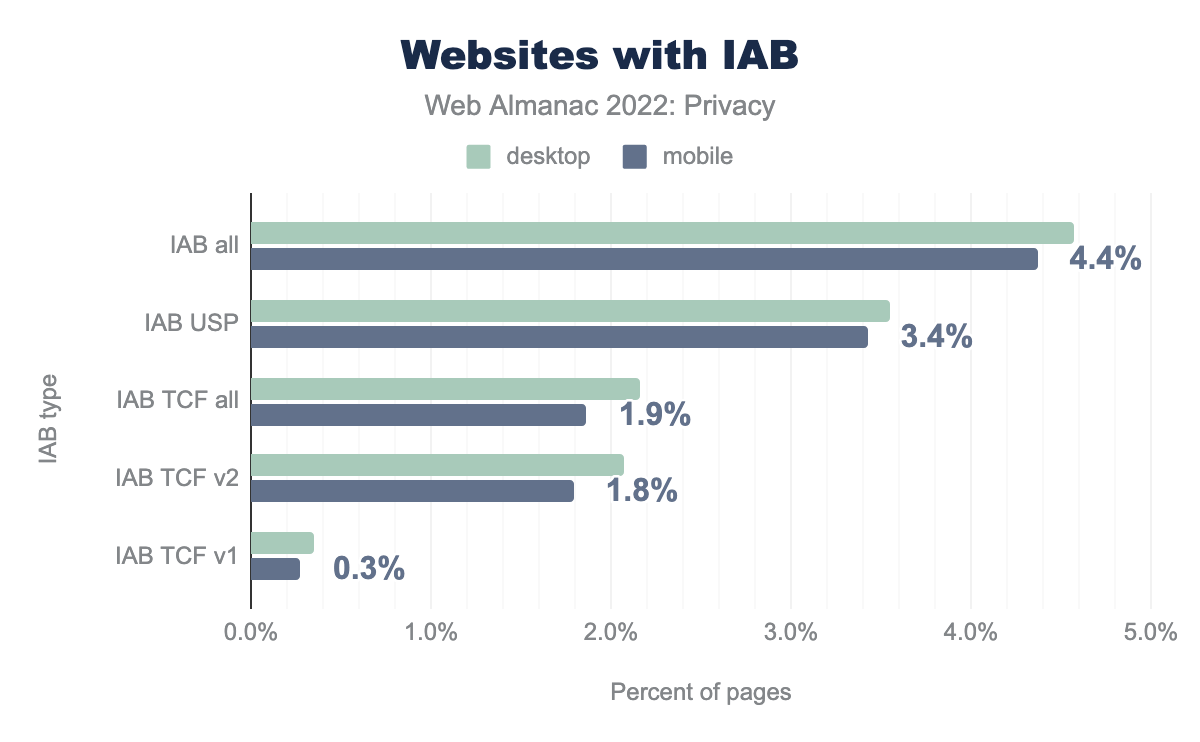

IAB consent frameworks

Compared to GDPR, the IAB Europe Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF) is an industry-standard where global vendors are involved. The goal is to establish communication between user consent and advertisers. TCF ensures that the websites in Europe are GDPR-compliant. IAB Tech Lab US developed the U.S. Privacy Technical Specifications (USP) was designed for the United States using the same concept of TCF.

We record that 4.6% of desktop websites use any IAB, with 3.5% using USP and 2.2% using IAB. Thus, we have recorded an increase for both specifications since last year. We would like to note here that our measurement is USA-based, so according to TCF, no consent banner is required for non-EU visits. So this can be the reason why we identify more websites with USP.

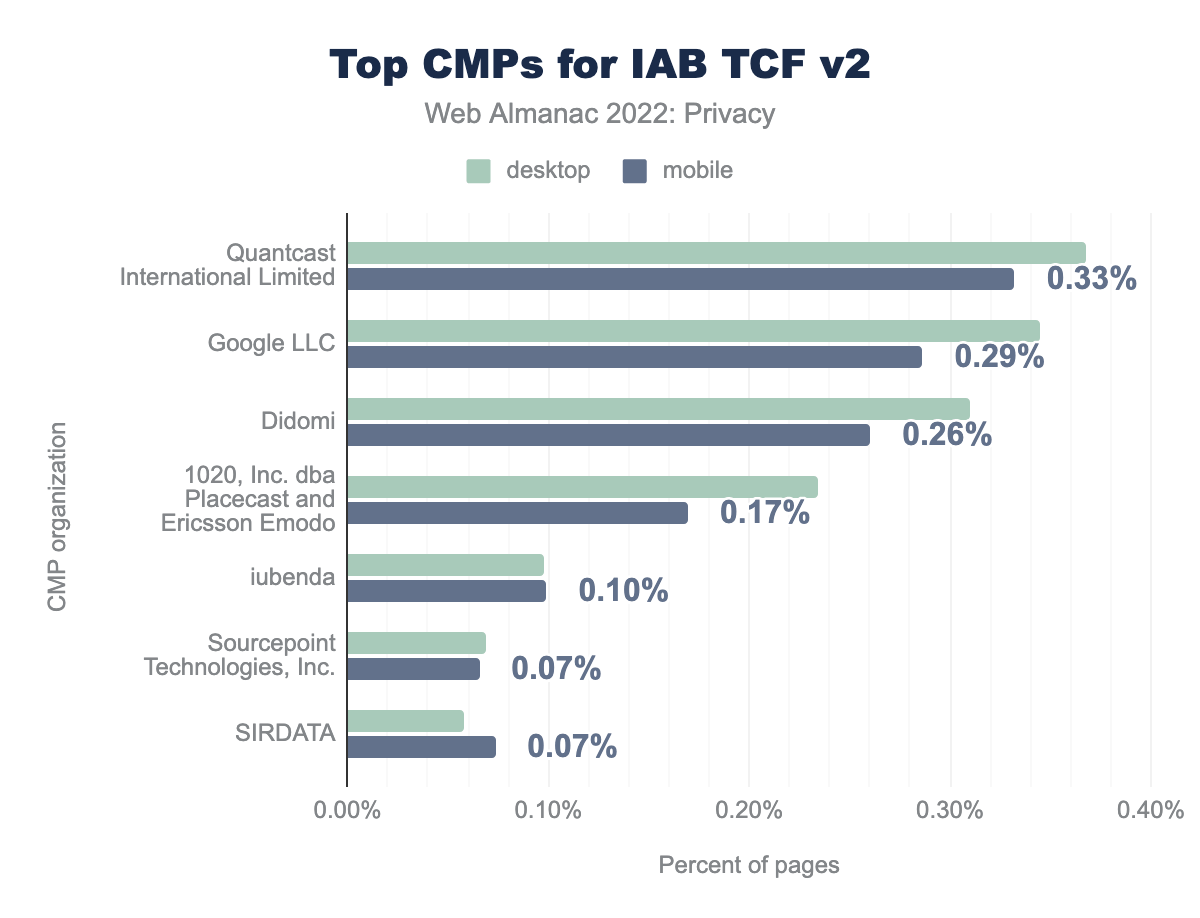

We see that Quantcast International Limited (0.37%), Google LLC (0.34%) and Didomi (0.31%) are popular CMP providers for IAB TCF v2.

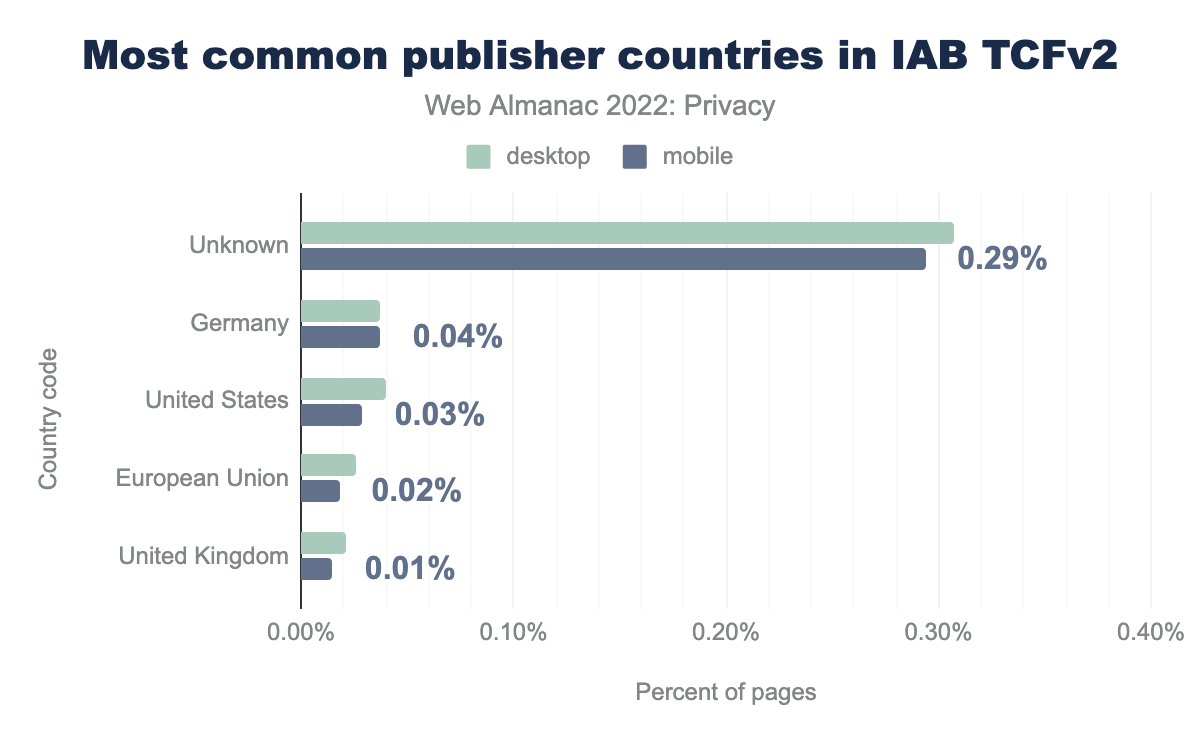

Our analysis shows that the most common publishers we identified are from Germany, the US, and the EU.

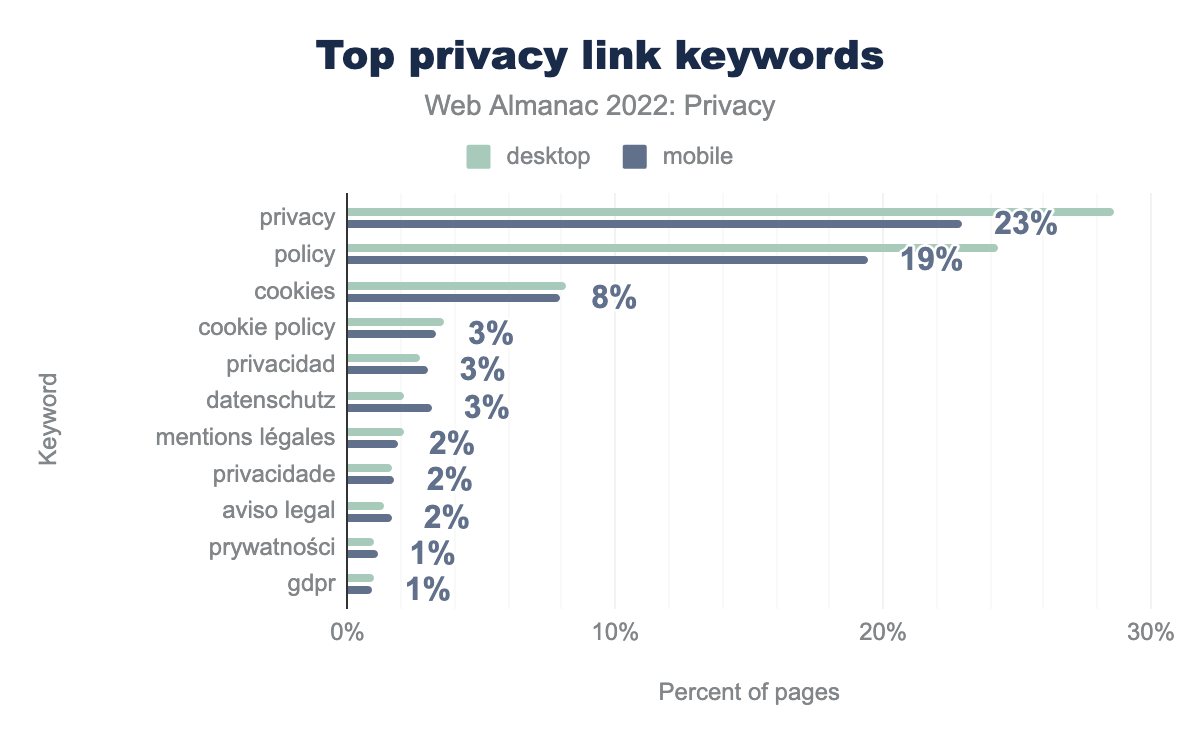

Privacy policy

Notifications regarding data processing do not always take place via a consent banner. They are also usually described in more detail on separate pages compared to such banners. On such pages, you will find information on integrated third parties, which data is processed for which purpose, etc. To identify such sites, we used the privacy-relevant signatures from a study. Using this method, we could determine that 45% of desktop websites (41% on mobile) contained a link on their home page to a privacy-related page. The figure below shows the distribution of the top privacy link keywords.

We see that privacy (29%), policy (24%), and cookies (8%) are the top keywords for such links.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we explored many different aspects related to our online privacy on the web. It is clear that in the past year a considerable amount of things have changed that affect our privacy, and this progress can be expected to continue in the following years. In short, there are some exciting times ahead of us. On the one hand, we found some unfortunate evolutions, which hopefully one day we will be able to refer to as the web’s legacy. Third-party tracking, mainly fueled by third-party cookies, is still ubiquitous with over 82% of websites containing at least a single tracker. Furthermore, there still is a non-negligible number of websites or web services that employ evasive techniques to circumvent anti-tracking measures.

On a more positive, privacy-preserving, track, we find that fewer sites are trying to access potentially sensitive information from browser APIs. Hopefully, this remains the case with the new APIs that are introduced in browsers on a regular basis.

Generally, it seems that websites are starting to hear the call of users to respect their privacy—a call that is getting louder and louder. More and more sites are switching to employing browser features that restrict the information that is sent to third parties. Furthermore, mainly motivated by privacy regulations such as GDPR and CCPA, we are seeing a clear increase —almost 60%—in the adoption of consent management platforms (CMPs), giving users more control over which information they want to share.

Finally, on the side of the browsers, we are also seeing a strong evolution towards providing users with more control of their online privacy. Next to the features that several privacy-focused browsers offer as a built-in solution, there is also the Privacy Sandbox initiative that aims to continue providing the current functionalities on the web—such as targeted advertising, anti-fraud, attribution of purchases, etc.—without the nefarious side-effects of cross-site tracking. Although the development is still in fairly early stages, we see that web services on a substantial number of websites are already opting-in to the Origin Trial. As such, the features are extensively being tested, and are likely to become a persistent part of the web.

While it may still take a couple of years to finally get there, we are transitioning towards a web that gives users more control over what they want to share with which parties. We can see this convergence on both sides of the spectrum: on the one hand initiated by the website, and on the other hand enforced by the browser. We can be hopeful that in the not-so-distant future the data we share, is the data that we intend to share, and the journey on the web that we take on a day-to-day basis no longer needs to be collected, shared, and analyzed by the numerous trackers that we currently encounter—in the hope of respectfully tomorrow for all.